Raman

Raman spectroscopy enables noninvasive blood glucose monitoring in compact MIT device

Dec 08 2025

Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have created a compact Raman spectroscopy device that measures blood glucose through the skin with needle-free readings comparable to commercial continuous monitors, paving the way for wearable, watch-sized diabetes sensors

A noninvasive method to measure blood glucose levels which has been under development at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) could spare people with diabetes from finger-prick tests several times a day or reduce their dependence on bodily-invasive continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) systems.

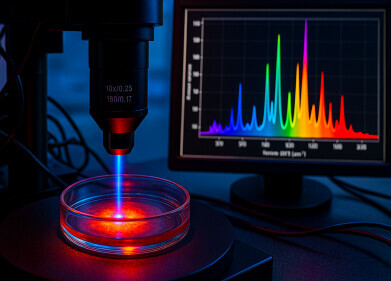

The MIT team has applied Raman spectroscopy – a light-based analytical technique that reveals the chemical composition of tissues – and developed a currently shoebox-sized instrument that quantifies blood glucose through intact skin. The device uses near-infrared light to interrogate molecular vibrations in the skin and underlying interstitial fluid, then infers glucose concentration from the resulting spectral signal, without the need for needles or implanted wires.

In healthy volunteer tests, measurements from the Raman device closely matched those from commercially available CGM sensors that require insertion of a wire just under the skin. The proof-of-concept system described in the present work is far too large to wear for everyday use, but the researchers have already created a smaller wearable prototype that is now under evaluation in a clinical study.

“For a long time, the finger stick has been the standard method for measuring blood sugar, but nobody wants to prick their finger every day, multiple times a day.

“Naturally, therefore, many diabetic patients under-test their blood glucose levels, which can lead to serious complications,” said Dr. Jeon Woong Kang, a research scientist at MIT and senior author of the study.

“If we can make a noninvasive glucose monitor – with high accuracy – then almost everyone with diabetes will benefit from this novel technology,” he added.

MIT postdoctoral researcher Dr. Arianna Bresci is lead author of the study. Its co-authors include Professor Peter So, director of the MIT Laser Biomedical Research Center (LBRC) and also the biological engineering and mechanical engineering at MIT, together with Dr. Youngkyu Kim of Apollon Inc and Dr. Miyeon Jue who is the South Korea biotechnology company’s chief technical officer.

Most people with diabetes still rely on capillary blood samples, obtained by finger-prick and applied to a test strip, to measure their blood glucose with a handheld glucometer. An increasing number use wearable CGM systems instead. These place a filament sensor into the interstitial fluid beneath the skin, usually on the upper arm or abdomen, and transmit glucose readings to a receiver or smartphone. Although these devices provide near-continuous data and support tighter glycaemic control, they can cause skin irritation and need to be replaced every 10 to 15 days.

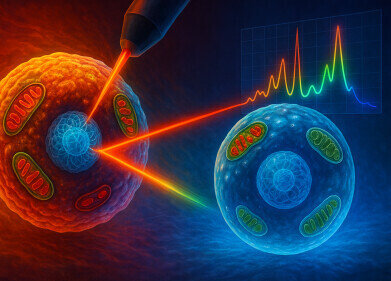

To create devices that would be more comfortable and potentially more acceptable for long-term use, researchers at the MIT Laser Biomedical Research Center have pursued noninvasive sensors based on Raman spectroscopy. In Raman spectroscopy, a beam of monochromatic light interrogates a sample, and a small fraction of photons scatter inelastically, with energy shifts that reflect specific molecular vibrations. Analysis of this scattered light yields a molecular ‘fingerprint’ that reveals the chemical composition of tissue or cells.

In 2010, scientists at the LBRC showed that they could indirectly estimate glucose levels by comparing Raman signals from the interstitial fluid that bathes skin cells with a reference measurement of blood glucose. Although this approach produced reliable measurements, it depended on a calibration step with blood samples and was not practical for a stand-alone glucose monitor that patients could use independently.

The group later reported a key advance that enabled direct detection of glucose-specific Raman signals from intact skin. Under typical conditions, the Raman signal from glucose is extremely weak in comparison with the many other spectral features generated by proteins, lipids, water and other molecules in tissue.

The MIT team found that by shining near-infrared light onto the skin at a different angle from the collection optics, they could suppress much of the unwanted background and selectively amplify the glucose-related component.

Those experiments used benchtop equipment roughly comparable in size to a shoebox. Since then, the researchers have focused on ways to reduce the footprint of the system, lower cost and simplify the optical design, while maintaining clinically useful accuracy.

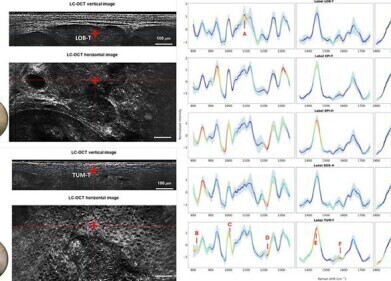

In the latest study, they achieved a much smaller device by measuring only three bands – that is, three spectral regions that correspond to specific molecular features – within the Raman spectrum. A conventional Raman spectrum can contain about 1,000 distinct bands, but the team identified a minimal set that still carried enough information to determine blood glucose concentration. The final configuration uses one band that corresponds primarily to glucose and two background bands that allow compensation for changes in tissue or measurement conditions.

Typically, Raman instruments acquire the full spectrum which requires relatively complex and costly spectrometers and detectors. By contrast, the MIT researchers showed that a device that targets three carefully selected spectral bands can infer glucose values with similar accuracy while at the same time using simpler components and in a more compact device.

“By refraining from acquiring the whole spectrum – which has a lot of redundant information – we [went] down to three bands selected from about 1,000,” said Bresci.

“With this novel approach, we can change the components commonly used in Raman-based devices, and save space, time, and cost,” she added.

In a clinical study at the MIT Center for Clinical Translation Research (CCTR), the team applied the shoebox-sized prototype to a healthy volunteer during a four-hour session. The subject rested an arm on the device so that a near-infrared beam passed through a small glass window to illuminate the skin. Each measurement required slightly more than 30 seconds with the researchers obtaining readings at five-minute intervals.

During the session, the volunteer consumed two drinks, each containing 75 grams of glucose. This protocol induced substantial rises and falls in blood glucose concentration, which allowed head-to-head comparison of the Raman-based measurements with two invasive commercial continuous glucose monitors worn by the subject. The Raman device achieved accuracy that the authors report as comparable to the commercial sensors, within the constraints of the small study.

Since completion of that trial, the group has created a smaller prototype about the size of a mobile telephone. This version integrates the optical and electronic components into a form factor suitable to strap to the body. The device is now under test at the MIT CCTR as a wearable monitor in healthy and prediabetic volunteers. The researchers intend to launch a larger study next year in collaboration with a local hospital, which will for the first time include people with diabetes.

Alongside miniaturisation, the team has begun to address user-to-user variability. Skin pigmentation, tissue composition and anatomical site can all influence optical measurements. The researchers therefore also explore strategies to ensure robust performance across a wide range of skin tones and physiological conditions, so that the device can provide accurate readings in diverse patient populations.

The long-term goal is a watch-sized Raman sensor that can deliver reliable, factory-calibrated glucose readings without needles or disposables. If successful, such a device could lower barriers to frequent glucose monitoring, support tighter day-to-day glycaemic control and potentially reduce long-term complications for more than 400 million people worldwide who live with diabetes.

The work has received funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Korean Technology and Information Promotion Agency for Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs), and Apollon Inc.

For further reading please visit: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5c01146

Digital Edition

Lab Asia Dec 2025

December 2025

Chromatography Articles- Cutting-edge sample preparation tools help laboratories to stay ahead of the curveMass Spectrometry & Spectroscopy Articles- Unlocking the complexity of metabolomics: Pushi...

View all digital editions

Events

Jan 21 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 28 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 29 2026 New Delhi, India

Feb 07 2026 Boston, MA, USA

Asia Pharma Expo/Asia Lab Expo

Feb 12 2026 Dhaka, Bangladesh