Raman

Optical photothermal IR spectroscopy maps microplastics in human tissue without damage

Nov 14 2025

A research team drawn from the Medical University of Vienna and the Research Center for Non-Destructive Testing has developed a novel optical photothermal infrared spectroscopy method to identify and localise microplastic particles in routine pathology samples without destruction of tissue

Worldwide microplastic pollution continues to rise but research into its impact on human health has been hampered by technical limitations and challenges. Until now suitable techniques have been unable to identify microplastic particles inside the body with any precision while keeping the tissue sample intact.

Research projects by a scientific team led by the Medical University of Vienna (MUV) – in collaboration with partner institutions – has now developed a novel approach that can localise microplastics in tissue in a non-destructive manner, with high spatial resolution, so that the exact position of the particles within preserved tissue structures was visible.

A central challenge so far has been that available analytical methods either destroy the tissue to extract and identify microplastics, or they do not provide information about the precise location of the particles within the tissue architecture. Without spatial information, it has been difficult to link microplastics to specific lesions, cell types or pathological processes.

The study, which have recently appeared in the journals Analytical Chemistry and Scientific Reports, has the potential to clarify if links exist between exposure to microplastic and the burden of chronic disease.

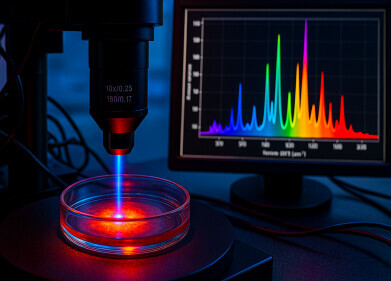

The work was conducted in close cooperation with the Research Center for Non-Destructive Testing (RECENDT) in Linz, Austria, using a method called optical photothermal infrared spectroscopy (OPTIR) was applied. It has already seen use in other material science contexts.

Optical photothermal infrared spectroscopy was originally developed to visualise chemical structures in complex materials with high spatial resolution, for example to map polymers or composite materials. In this study, the scientific team led by Professor Lukas Kenner from the Clinical Institute of Pathology at MUV has shown for the first time that the same principle can apply to human tissue samples and can provide spatially resolved information on microplastic contamination.

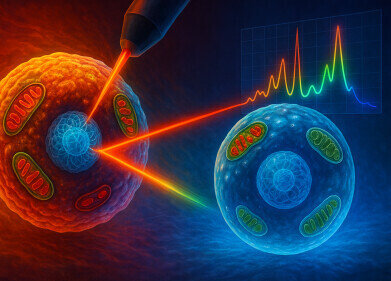

OPTIR exploits the way in which different materials give a specific response to infrared laser light. A pulsed infrared laser illuminates the sample and locally heats microscopic regions. Plastics such as polyethylene (PE), polystyrene (PS) and polyethylene terephthalate (PET) respond in a characteristic way because of their distinct chemical structures and bond vibrations.

A second, visible or near-infrared probe light detects these subtle thermal changes at the sample surface. The resulting signals form a so-called infrared fingerprint that permits unambiguous chemical identification of the particles inside the sample, while the surrounding tissue remains structurally intact and suitable for subsequent analysis.

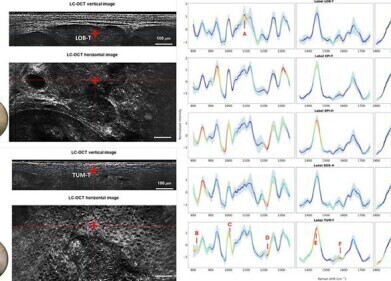

The investigative concept that the team has now developed contained a crucial step for medical application. The researchers have for the first time applied OPTIR successfully to formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples – the type of tissue that clinical pathology departments routinely examine under the microscope and store in archives for many years.

FFPE preparation is standard practice in diagnostic pathology, because it preserves tissue architecture and cellular detail, but it allows long-term storage at room temperature. In the OPTIR workflow, the FFPE tissue sections remained fully intact, which made it possible to link the chemical analysis directly to subsequent histological – microscopic – assessments or to genetic and molecular diagnostic procedures on the same regions of interest. This approach permitted not only the detection of microplastic particles but also their assessment in relation to tissue alterations such as inflammation or fibrosis.

“In the study… we were able to identify various microplastic particles in human colon tissue, including PE, PS and PET. These occurred strikingly often in areas with inflammatory changes,” reported Professor Kenner.

The team has interpreted this accumulation as a possible indication that microplastics may interact with inflamed or vulnerable regions of the intestinal wall, although causal relationships will require further investigation in larger cohorts. Additional experiments with mice and three-dimensional cell cultures also showed that extremely small particles with diameters of only 250 nanometres – 0.00025 millimetres – could be reliably detected by OPTIR.

Sensitivity is important because nanoscale particles may penetrate deeper into tissue and cells and may influence biological processes in different ways from larger fragments.

Polyethylene, polystyrene and polyethylene terephthalate are among the most widespread plastics in everyday life. Consumers encounter them in cling film, plastic bags, drinks bottles, food packaging and numerous other single-use or reusable items. Mechanical abrasion, degradation in the environment and fragmentation during production and disposal processes generate microplastics – generally described as particles of plastic that are smaller than five millimetres – that can enter the human body whether airborne, in water or with food.

Once ingested or inhaled, at least a proportion of these particles appear to cross epithelial barriers and to reach internal organs, although the extent and health implications of this process have remained unclear.

The health effects of microplastics have therefore become the subject of intense international research. Toxicologists, immunologists and epidemiologists have begun to explore whether long-term exposure to micro- and nanoplastics contributes to chronic inflammation, cancer, cardiovascular disease or metabolic disorders.

“Our established use of OPTIR technology shows for the first time that both are possible: precise chemical identification and preservation of spatial tissue information – a milestone for medical microplastic research,” said Professor Kenner.

He added that the ability to work directly on routine FFPE specimens means that very large collections of archived human tissue could become accessible for retrospective studies. Researchers can therefore analyse stored samples from patients with clearly defined diagnoses and outcomes to test hypotheses about microplastic burden and disease progression.

The MUV and RECENDT team now intends to extend the OPTIR approach to a wider range of tissues and disease states and to refine quantification protocols. In parallel, collaborations with epidemiological groups could help to integrate OPTIR-based microplastic mapping with clinical data, lifestyle factors and environmental exposure assessments.

For further reading please visit: 10.1021/acs.analchem.4c05400

Digital Edition

Lab Asia Dec 2025

December 2025

Chromatography Articles- Cutting-edge sample preparation tools help laboratories to stay ahead of the curveMass Spectrometry & Spectroscopy Articles- Unlocking the complexity of metabolomics: Pushi...

View all digital editions

Events

Jan 21 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 28 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 29 2026 New Delhi, India

Feb 07 2026 Boston, MA, USA

Asia Pharma Expo/Asia Lab Expo

Feb 12 2026 Dhaka, Bangladesh