-

-

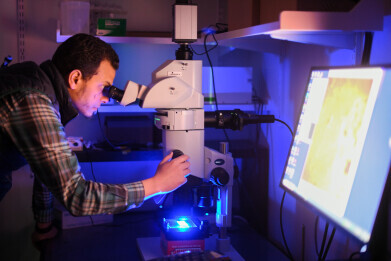

Dr. Osama Harraz, assistant professor of pharmacology at Larner College of Medicine, looks at brain vasculature through a widefield fluorescence microscope in his laboratory at the University of Vermont. Credit: David Seaver

Dr. Osama Harraz, assistant professor of pharmacology at Larner College of Medicine, looks at brain vasculature through a widefield fluorescence microscope in his laboratory at the University of Vermont. Credit: David Seaver

Research news

Brain blood flow restored in dementia models by replacing a missing lipid: study

Jan 02 2026

A preclinical study from the University of Vermont has linked excessive activity of the mechanosensor Piezo1 in brain blood vessels to impaired cerebral blood flow, a hallmark of several dementias

Scientists at the University of Vermont Robert Larner, M.D. College of Medicine, Burlington, Vermont, United States have reported a potential strategy to correct impaired cerebral blood flow, a dysfunction that commonly accompanies Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. In preclinical work the team has described how loss of a specific membrane phospholipid removes an inhibitory ‘brake’ from a mechanosensitive protein in blood vessel cells which then disrupts the fine control of blood delivery to brain tissue.

“This discovery is a huge step forward in our efforts to prevent dementia and neurovascular diseases,” said Dr Osama Harraz, assistant professor of pharmacology at Larner College and the principal investigator of the study.

“We are uncovering the complex mechanisms of these devastating conditions, and now we can begin to think about how to translate this biology into therapies,” Harraz added.

Dementias, including Alzheimer’s disease, affect tens of millions of people worldwide and prevalence has continued to rise as populations worldwide age. While much of dementia research has examined amyloid and tau pathology, neuroinflammation and neuronal dysfunction, clinicians and researchers have increasingly recognised that the brain’s blood supply is not merely a passive backdrop.

Cerebral blood flow must match local metabolic demand with high precision since neurons rely on a continuous supply of oxygen and glucose and don’t tolerate any interruptions well. Even modest, sustained deficits in microvascular perfusion can contribute to cognitive decline and can interact with neurodegenerative pathology to accelerate symptoms.

The Vermont study has focused on a protein called Piezo1*, which sits within the membrane of endothelial cells that line blood vessels. Piezo1 functions as a mechanosensory, responding to physical forces generated as blood moves through vessels. Its name derives from the Greek term for ‘pressure’ which captures its role as a molecular gauge of frictional and shear forces. When Piezo1 opens, it allows ions to pass through the cell membrane and initiates signalling cascades that can alter vessel tone and blood flow.

Prior work has suggested that Piezo1 activity can differ among people who carry particular genetic variants in the Piezo1 gene. The Vermont group has extended this line of enquiry by asking a broader question with direct relevance to dementia – what controls Piezo1 activity in brain blood vessels and what happens when that control fails?

In this study the team has described evidence that disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease are associated with increased Piezo1 activity in the brain vasculature. The term ‘channelopathy’ refers to a disease state that arises when an ion channel behaves abnormally, whether due to genetic change, altered regulation, or shifts in the cellular environment that affect how the channel opens and closes.

The team has centred attention on phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate – abbreviated to PIP2 – a phospholipid that forms part of the inner cell membrane. PIP2 has served as a crucial regulator of signalling pathways across biology, in part because it can interact with membrane proteins directly and because enzymes can convert it into other bioactive lipids. Ion channels are among the best-known molecular ‘clients’ of PIP2 as in many systems, adequate levels help channels to maintain stable gating behaviour, while depletion can destabilise control and drive overactivity.

According to the investigators, PIP2 acts as a natural inhibitor of Piezo1 in brain endothelial cells. When PIP2 levels fall, Piezo1 becomes overactive and the vascular signalling that governs cerebral blood flow decays. In practical terms, that imbalance can mean that vessels fail to dilate appropriately, blood distribution becomes less responsive to need, and brain tissue experiences a chronic shortfall in perfusion.

To test whether this imbalance is reversible, the researchers examined whether restoration of PIP2 could suppress Piezo1 activity and reset blood flow control. Their findings have suggested that addition of PIP2 back into the system reduced Piezo1 activity and restored a more typical pattern of cerebral blood flow in their preclinical models. While the work is a long way from being offered as a therapy in the clinic, it does suggest a clear mechanistic hypothesis. Boosting PIP2 availability – or otherwise recreating its inhibitory effect on Piezo1 – could represent a method to correct the functioning of a vascular factor in cognitive impairment.

The next challenge is to define precisely how PIP2 restrains Piezo1. One possibility is direct binding whereby the lipid interacts with specific regions of the Piezo1 protein and stabilise a closed, less active state. Another is indirect control through the membrane itself such that PIP2 alters local membrane charge and structure which can influence how membrane proteins move and how readily they transition between open and closed states. The group has indicated that future experiments will aim to disentangle these possibilities and to establish how disease-associated reductions in PIP2 remove the regulatory brake which can permit sustained Piezo1 overactivity and persistent impairment of cerebral blood flow.

This mechanistic focus matters because it is a factor in shaping therapeutic options. If direct binding dominates, drug developers could attempt to design small molecules or biologics that mimic the PIP2 interaction surface. However, if the membrane environment proves to be more important, researchers might instead explore strategies to preserve membrane lipid composition, protect PIP2 from pathological depletion, or deliver lipid formulations that restore inhibitory capacity within the endothelium. In either case, translational work will be needed to answer the hard questions about delivery, dosing, tissue specificity and safety, since systemic manipulation of a ubiquitous signalling lipid risks off-target effects.

For dementia research, the significance is not that a treatment has arrived, but that a specific, controllable vascular mechanism has emerged with a plausible molecular lever. Cerebral blood flow has long been an attractive target, yet it has often lacked the crisp, druggable pathways that make for practical therapies. By placing PIP2 and Piezo1 at the centre of a defined endothelial control circuit, the Vermont work has offered an avenue for future studies aiming to restore neurovascular function.

For further reading please visit: DOI-number-TK

* Study of Piezo1 (and Piezo 2) were recognised in the 2021 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine

Digital Edition

Lab Asia Dec 2025

December 2025

Chromatography Articles- Cutting-edge sample preparation tools help laboratories to stay ahead of the curveMass Spectrometry & Spectroscopy Articles- Unlocking the complexity of metabolomics: Pushi...

View all digital editions

Events

Jan 21 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 28 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 29 2026 New Delhi, India

Feb 07 2026 Boston, MA, USA

Asia Pharma Expo/Asia Lab Expo

Feb 12 2026 Dhaka, Bangladesh