-

-

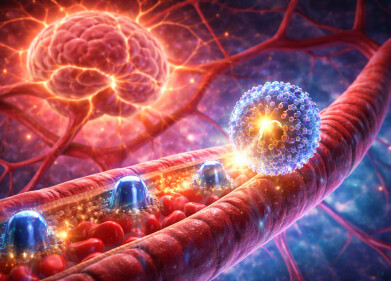

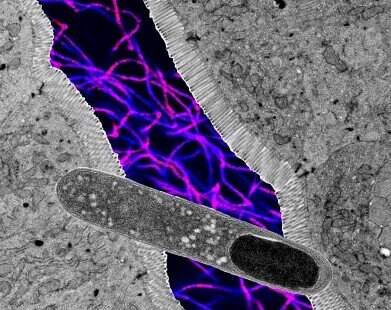

Collage of microscope images showing a rod-shaped Turicibacter (foreground), cross section of intestine, and fluorescent microscopy of more bacteria (background). Images not to scale. Credit: Kendra Klag

Collage of microscope images showing a rod-shaped Turicibacter (foreground), cross section of intestine, and fluorescent microscopy of more bacteria (background). Images not to scale. Credit: Kendra Klag -

.jpg) Dr. June Round in her laboratory. Credit: Charlie Ehlert / UofU Health

Dr. June Round in her laboratory. Credit: Charlie Ehlert / UofU Health

Research news

Specific single gut bacterium linked to improved metabolic health and reduced weight gain in mice

Jan 01 2026

University of Utah research has identified a single gut bacterium that has reduced weight gain and improved metabolic markers in mice fed with a high-fat diet, offering fresh insight into how targeted manipulation of the gut microbiome might support metabolic health

The gut microbiome has long been recognised as a critical determinant of human health, with growing evidence to link its composition to body weight, metabolic control and disease risk. Differences in the communities of bacteria and fungi that inhabit the gastrointestinal tract have been associated with obesity and weight gain, which has raised the possibility that deliberate changes to the microbiome could help to improve metabolic outcomes. The challenge has been scale given each individual gut contains hundreds of microbial species, many of which interact in complex and poorly understood ways.

Researchers at the University of Utah (UofU), Salt Lake City, Utah, United States, have now reported evidence that a single bacterial genus – Turicibacter – has improved metabolic health and reduced weight gain in mice fed a high-fat diet. The work has also shown that people with obesity tend to have lower levels of Turicibacter, which suggests that the bacterium may contribute to healthy weight maintenance in humans. Although the findings remain based on animal models, the results have pointed towards novel strategies to influence weight and metabolism through modulation of gut bacteria.

Previous work by the same research group had demonstrated that a broad consortium of approximately 100 gut bacterial species was able to protect mice from diet-induced weight gain. Isolating the contribution of individual microbes from this collective effect proved technically demanding. Many gut bacteria are highly sensitive to oxygen and cannot survive exposure to air requiring their study to be under strictly controlled anaerobic conditions.

“The microbes that live in our gut don’t like to [be] outside the gut at all,” explained Kendra Klag, a doctoral candidate at the Spencer Fox Eccles School of Medicine at the UofU and first author on the study.

“Many are killed by the presence of oxygen and must be handled exclusively in airtight environments,” she said.

After several years devoted to culturing and testing individual bacterial species, the researchers identified Turicibacter as having a striking effect on host metabolism. When administered to mice consuming a high-fat diet, Turicibacter alone reduced weight gain, lowered blood sugar and decreased circulating fat levels.

“I didn’t think one microbe would have such a dramatic effect. I thought it would be a mix of three or four,” said Professor June Round of microbiology and immunology at UofU Health and senior author on the paper.

“So, when [Klag] brought me the first experimental data with Turicibacter and the mice were staying really lean, I was like: ‘This is so amazing.’

“It’s pretty exciting when you see those types of results,” she added.

Further experiments suggested that Turicibacter exerted its metabolic effects through the production of fatty molecules that were absorbed by the small intestine. When the researchers supplemented a high-fat diet with purified fats derived from Turicibacter, they observed weight-controlling effects comparable to those seen with the live bacterium itself. This finding indicated that bacterial lipids, rather than the physical presence of the microbe, played a central role in mediating the observed benefits.

However, the precise identity of the most important molecules has yet to be determined. Turicibacter produces thousands of distinct lipid compounds, which Klag described as a ‘lipid soup’. The research team has indicated that future work will focus on identifying which of these molecules are the most influential, and for potential therapeutic development.

The study has also shown that Turicibacter influenced host metabolism by altering levels of ceramides, a class of fatty molecules produced by the host. Ceramide levels tend to rise in response to a high-fat diet, and elevated ceramides have been associated with metabolic disorders such as type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

In mice that received Turicibacter or its lipid products, ceramide levels remained low despite consumption of a high-fat diet, which suggested a mechanism by which the bacterium improved metabolic resilience.

The relationship between diet and Turicibacter proved to be reciprocal. The researchers found that the bacterium struggled to survive in environments with very high fat content. As a result, mice fed a high-fat diet lost Turicibacter from their gut microbiome unless the bacterium was regularly reintroduced. This observation has highlighted a complex feedback loop, in which dietary fat suppressed Turicibacter populations, while Turicibacter-derived lipids improved the host’s capacity to cope with dietary fat.

The authors have emphasised that Turicibacter is unlikely to act alone in shaping metabolic health. Many gut bacteria probably contribute to weight regulation and metabolic control, often through overlapping or complementary mechanisms. They have also cautioned against direct extrapolation of the findings to humans.

“We have improved weight gain in mice but have no idea if this [will also be] true in humans,” Round said.

Despite these uncertainties, the researchers have argued that the identification of a single bacterium with such pronounced metabolic effects provides a valuable starting point. By defining the molecular products responsible for these effects, it may become possible to design targeted interventions that mimic or enhance beneficial microbial functions without the need to introduce live bacteria.

“Identifying what lipid is having this effect is going to be one of the most important future directions.

“Both from a scientific perspective, because we want to understand how it works, and from a therapeutic standpoint.

“Perhaps we could use this bacterial lipid, which we know really doesn’t have a lot of side effects because people already have it in their guts, as a way to maintain a healthy weight,” Round said.

Klag also highlighted the broader implications for drug discovery.

“With further investigation of individual microbes, we will be able to turn microbes into medicine and identify bacteria that are safe to create a consortium of different organisms that people with different diseases might lack.

“Microbes represent an extraordinary resource for drug discovery. At present, we know only the very tip of the iceberg when it comes to what these bacterial products can do,” she added.

Taken together, the findings have reinforced the view that the gut microbiome is not passive but an active area for metabolic regulation. While translation to human health will require substantial further research, the study has added to the body of evidence that members of the gut microbial community exert powerful and precise effects on a host’s physiology.

For further reading please visit: 10.1016/j.cmet.2025.10.007

Digital Edition

Lab Asia Dec 2025

December 2025

Chromatography Articles- Cutting-edge sample preparation tools help laboratories to stay ahead of the curveMass Spectrometry & Spectroscopy Articles- Unlocking the complexity of metabolomics: Pushi...

View all digital editions

Events

Jan 21 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 28 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 29 2026 New Delhi, India

Feb 07 2026 Boston, MA, USA

Asia Pharma Expo/Asia Lab Expo

Feb 12 2026 Dhaka, Bangladesh