-

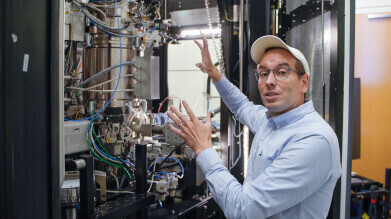

Dr. Robert Hovden, an associate professor of materials science and engineering, describes how an upgraded cryo-electron microscope works at the Michigan Center for Materials Characterization. Photo: Eric Shaw, Office of the Vice President for Research

Dr. Robert Hovden, an associate professor of materials science and engineering, describes how an upgraded cryo-electron microscope works at the Michigan Center for Materials Characterization. Photo: Eric Shaw, Office of the Vice President for Research

Electron

Scientists achieve 10-hour atomic resolution imaging at near absolute zero using liquid helium microscope system

Oct 02 2025

A research team from the University of Michigan and Harvard University in the United States has developed a liquid-helium-cooled sample holder that allows electron microscopes to maintain specimens at near absolute zero for more than 10 hours, enabling atomic-resolution imaging of superconductors, quantum materials and neuromorphic computing candidates

Michigan and Harvard scientists have reported that they can now sustain specimens at temperatures close to absolute zero for more than 10 hours, while capturing images resolved to the level of individual atoms with an electron microscope. The capability has come from a liquid-helium-cooled sample holder designed by a team drawn from the two American universities.

Conventional platforms have usually been able to maintain such extreme temperatures – approximately 20.4 Kelvin above absolute zero which is −252.8 °C – for only a few minutes, rarely more than a few hours. However, to image candidate materials for advanced technologies at atomic resolution, longer periods of time are needed.

These materials include superconductors that transmit electricity without heat losses, quantum computers that could perform some calculations millions of times faster than conventional machines, and neuromorphic computers that seek to improve efficiency by imitating the architecture of the human brain. Such materials generally exhibit their distinctive properties only in extreme cold.

“When the atoms get that cold, they don’t move much and that radically changes the behaviour of the material,” said Dr. Robert Hovden, associate professor of materials science and engineering at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and is the study’s corresponding author.

“A lot of really cool things happen. [Pun not intended – Ed.] Metals can become insulators or superconductors and we can design qubits and novel computer memories around them.

“If we want to understand how these properties emerge, we need to observe the materials at these low temperatures for the entire duration of an experiment.”

Although ultracold microscopy at 77 Kelvin (−196 °C) has enabled researchers to capture atomic-level images of materials and proteins, even colder conditions are required to visualise quantum properties and achieve finer resolutions.

Liquid helium offers the possibility of reaching closer to absolute zero – at 0 K (−273.15 °C) – because helium condenses at 4 K (−269.15 °C). Yet until now, practical barriers have prevented its prolonged use in microscopy. In most modern transmission electron microscopy platforms, the sample is attached to a rod connected to a dewar, a thermos-like container.

When filled with nitrogen or helium, the dewar cools both the rod and the sample. However, the liquid boils vigorously inside the container, disturbing the sample and reducing image resolution. The problem is particularly severe with liquid helium, which evaporates faster and boils more energetically.

“It’s like pouring water on hot lava.

“Not only do you get all these vibrations from the boiling liquid, but the temperature swings all over the place, so the rod contracts and you can’t hold the exact temperature you need,” said Hovden.

The team’s instrument maintained sample temperatures as low as 20 K (−252.8 °C) for more than 10 hours, with only 0.002 K (0.002 °C) of variation. This control, which is ten times finer than existing systems, enabled the team to expose specimens to carefully controlled thermal gradients while directly observing changes in their atomic structure.

“Being able to see the atomic arrangement as the material changes could be the key to understanding and harnessing the atomic and nanoscale processes that give quantum materials their amazing properties,” said Dr. Ismail El Baggari, a physicist at Harvard University’s Rowland Institute and also a corresponding author.

The instrument achieved stable cooling by means of a heat exchanger connected to the sample holder. Helium gas evaporated as it was pumped through the exchanger, cooling the specimen before release through an exhaust vent. Existing closed-loop holders have also used helium, but their vibrations have prevented atomic-resolution imaging. In the new design, flexible tubing and rubber insulators on either end of the heat exchanger reduced vibrations caused by the evaporating helium, securing sharper images.

Such precision demanded exacting mechanical standards. Small deviations in fabrication introduced vibrations or leaks.

“Figuring out how to fabricate this thing and test it inside the microscope were huge hurdles to overcome,” said Emily Rennich, the study’s first author, who led construction of the system as an undergraduate in mechanical engineering at the University of Michigan and is now a doctoral candidate at Stanford University, California.

“I didn’t actually have very many manufacturing or design skills before I started. Only through a lot of trial and error – and talking to other machinists – were we able to make something that worked.”

The system is already in operation at the Michigan Centre for Materials Characterization, which is supported through indirect cost allocations on federal grants. The facility is providing access to researchers nationwide who are pursuing experiments that had previously been impractical.

“I’m excited about this breakthrough, something I’ve anticipated for nearly a decade,” said Dr. Miaofang Chi, corporate fellow at Oak Ridge National Laboratory and professor of mechanical engineering and materials science at Duke University, who was not involved in the work.

“The team’s achievement will have a lasting impact,” she added.

For further reading please visit: 10.1073/pnas.2509736122

Digital Edition

Lab Asia Dec 2025

December 2025

Chromatography Articles- Cutting-edge sample preparation tools help laboratories to stay ahead of the curveMass Spectrometry & Spectroscopy Articles- Unlocking the complexity of metabolomics: Pushi...

View all digital editions

Events

Jan 21 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 28 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 29 2026 New Delhi, India

Feb 07 2026 Boston, MA, USA

Asia Pharma Expo/Asia Lab Expo

Feb 12 2026 Dhaka, Bangladesh