-

-

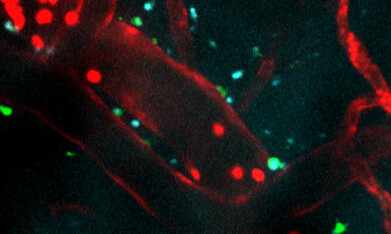

Immune cells (shown in red) injected into an area injured by ischemic stroke. The peptide treatment (blue) successfully crosses the blood-brain barrier (red). Microglia (green) become active and surround the treatment, which indicates an elevated immune response. Recorded over five minutes and sped up here 60x. Credit: Northwestern University

Immune cells (shown in red) injected into an area injured by ischemic stroke. The peptide treatment (blue) successfully crosses the blood-brain barrier (red). Microglia (green) become active and surround the treatment, which indicates an elevated immune response. Recorded over five minutes and sped up here 60x. Credit: Northwestern University

Research news

Nanomaterial directly injected into brain after stroke provides novel protection that aids reperfusion

Jan 12 2026

Northwestern University researchers have reported a novel injectable nanomaterial that crossed the blood–brain barrier and reduced secondary brain injury after ischaemic stroke in mice, raising the prospect of a regenerative therapy to complement existing clot-removal treatments

When a person experiences a stroke, clinicians have to restore blood flow to the brain as rapidly as possible to prevent death and limit immediate injury. Paradoxically, the sudden return of blood to oxygen-deprived tissue can itself trigger a secondary wave of damage – neuronal loss and inflammation – risking higher levels of long-term disability. Scientists at Northwestern University, Chicago, USA, have now reported a regenerative nanomaterial designed to protect the brain during this vulnerable period following reperfusion.

In a preclinical mouse model of acute ischaemic stroke, the team administered a single intravenous dose of the therapy immediately after restoration of blood flow. Ischaemic stroke – the most common form of the condition – occurs when a blood clot obstructs a cerebral vessel and deprives brain tissue of oxygen.

The experimental treatment successfully crossed the blood–brain barrier, a long-standing obstacle for neurological drug development, and localised to the site of injury. Compared with untreated animals, treated mice showed markedly less brain tissue damage, reduced inflammatory signalling and no evidence of organ toxicity or adverse immune responses.

The findings suggest that this approach could one day complement established clinical strategies that focused almost exclusively on reopening blocked vessels through thrombolytic drugs or mechanical clot removal.

“Current clinical approaches are entirely focused on blood flow restoration,” said Dr. Ayush Batra, co-corresponding author of the study and associate professor of neurology and pathology at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine.

“Any treatment that facilitates neuronal recovery and minimises injury would be very powerful, but that holy grail does not yet exist.

“This study is promising because it has led us down a pathway to develop technologies and therapeutics to address this unmet need,” he added.

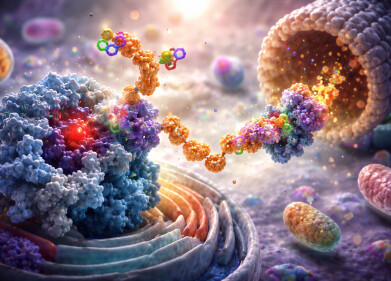

The injectable therapy was based on supramolecular therapeutic peptides, a platform developed by Professor Samuel I. Stupp at Northwestern. These dynamic molecular assemblies, often referred to as ‘dancing molecules’, had previously demonstrated regenerative potential in spinal cord injury models.

In a 2021 study, a single injection of related materials at the site of severe spinal cord damage reversed paralysis and promoted tissue repair in mice. The latest work extended this concept by showing that similar assemblies could be delivered intravenously, without surgery or direct injection into the brain.

“One of the most promising aspects of this study is that we were able to show this therapeutic technology can be applied in a stroke model and that it can be delivered systemically,” said Stupp, co-corresponding author and board of trustees professor of materials science and engineering, chemistry, medicine and biomedical engineering at Northwestern. Previously it has also shown promise in spinal cord injury,

He added that the ability to cross the blood–brain barrier could also have implications for traumatic brain injury and neurodegenerative disorders such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

Acute ischaemic stroke accounts for about 80 per cent of all strokes in the USA and remains a leading cause of death and long-term disability worldwide. Severe cases frequently result in permanent impairment that affected quality of life, return to work and participation in family and social life.

“It is a significant personal and emotional burden on patients, but [can] also [add] a financial burden on families and communities.

“To reduce … disability with a therapy that could help to restore function and minimise injury would have a powerful long-term impact,” Batra said.

To mirror clinical practice as closely as possible, the researchers first blocked cerebral blood flow in mice to simulate a major stroke and then restored it through reperfusion, reflecting real-world emergency treatment. Animals were monitored for seven days, during which no significant biocompatibility issues emerged.

Advanced imaging confirmed that the therapeutic peptides accumulated at the injury site. Treated mice exhibited less inflammation and a dampened harmful immune response compared with controls.

According to Stupp, the benefit arose from a combination of pro-regenerative and anti-inflammatory effects. Once a clot formed, harmful molecules accumulated in the affected tissue, and sudden reperfusion released them into circulation, where they could exacerbate damage. The supramolecular peptides carried anti-inflammatory activity that countered this effect while also supporting repair of neural networks.

At a molecular level, the therapy relied on careful tuning of collective molecular motion, which allowed the assemblies to engage effectively with constantly moving cellular receptors. These interactions triggered signals that encouraged neuron repair, promoted axons regrowth and helped to re-establish communication between nerve cells. This capacity for plasticity underpinned the brain’s ability to adapt and rebuild connections after injury.

Earlier versions of the technology had been injected as liquids that rapidly formed gel-like networks of nanofibres at the injury site, mimicking the extracellular matrix of neural tissue. For systemic delivery in stroke, the researchers reduced the concentration of peptide assemblies to avoid clot formation in the bloodstream. Smaller aggregates crossed the blood–brain barrier more readily, after which larger nanofibre structures formed within brain tissue to enhance the therapeutic effect.

“We chose for this stroke study one of the most dynamic therapies we had in terms of its molecular structure so that supramolecular assemblies would have a better probability of crossing the blood–brain barrier,” Stupp said.

Failure of otherwise promising therapies to cross the blood–brain barrier had hindered progress in neuroscience research for many years. Batra noted that during acute stroke treatment, permeability of this barrier increased transiently at the injured site, creating a brief opportunity for intervention.

“Add to that a dynamic peptide that is able to cross [the blood–brain barrier] more readily, and you are optimising the chances that your therapy is going where you want it to go,” he said.

Further work will need to determine whether the approach can support longer-term functional recovery. Many patients experienced progressive cognitive decline during the year following a stroke, and the team planned extended studies with more sophisticated behavioural assessments. Researchers also intended to explore incorporation of additional regenerative signals into the peptide platform to enhance efficacy.

For further reading please visit: ‘Toward Development of a Dynamic Supramolecular Peptide Therapy for Acute Ischemic Stroke’

Digital Edition

Lab Asia Dec 2025

December 2025

Chromatography Articles- Cutting-edge sample preparation tools help laboratories to stay ahead of the curveMass Spectrometry & Spectroscopy Articles- Unlocking the complexity of metabolomics: Pushi...

View all digital editions

Events

Jan 21 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 28 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 29 2026 New Delhi, India

Feb 07 2026 Boston, MA, USA

Asia Pharma Expo/Asia Lab Expo

Feb 12 2026 Dhaka, Bangladesh