Laboratory events news

ELRIG 2025: Imaging flow cytometry heralds shift from cell discovery to clinical translation

Dec 17 2025

At ELRIG 2025 in Stevenage, AstraZeneca’s Global Leader for Flow Cytometry, Dr Raffaello Cimbro, outlined how imaging flow cytometry has evolved from a specialist tool into a cornerstone technology capable of linking cell phenotype, morphology and drug response from early discovery through to clinical application

At the ELRIG conference held at the GSK campus in Stevenage in November 2025, Dr Raffaello Cimbro, director and global leader of flow cytometry in the US and UK for AstraZeneca (AZ), spoke to a detailed and ambitious vision for the role of imaging flow cytometry in drug discovery and clinical translation.

As head of a global team supporting more than 650 scientists across various AZ sites and around 45 project lines, Dr Cimbro characterised imaging flow cytometry as a technological step change rather than a specialist refinement. He said that it has begun to connect cellular phenotype, function and therapeutic response in ways not previously possible with conventional flow cytometry.

He began by recalling that traditional flow cytometry remains one of the most cost-effective and widely used single-cell technologies in discovery research. Modern instruments can capture tens of thousands of events per second and detect more than 30 fluorescence parameters in a single tube. However, he stressed that the technique has an inherent limitation given that it provides no information on cellular morphology or spatial protein distribution.

“Flow cytometry tells you how many times a word appears in a book, but never where or how it is used,” said Cimbro.

“Imaging flow cytometry lets us read the pages and understand the context,” he added.

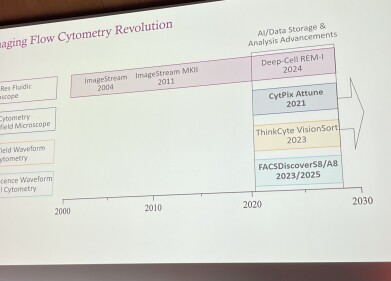

Imaging flow cytometry itself is not a recent invention with the first commercial systems appearing in 2004. For nearly two decades a single platform has dominated the field. Recent breakthrough in the technology, Cimbro said, has been computational. Advances in artificial intelligence (AI), image storage and analytical software have now enabled laboratories to manage the immense datasets that these instruments produce.

He detailed the four principal categories of imaging cytometry that are now in use. The first adds a high-speed camera to a standard flow cytometer to capture brightfield or limited fluorescence images. The second builds on this concept by integrating high-resolution optics for label-free imaging at high throughput. The third category, comprising spectral imaging systems, combines very high parametric fluorescence with multiple imaging channels and real-time sorting guided by image-derived features. And the last consists of label-free instruments that analyse scattered light to produce a cell’s ‘fingerprint’, from which information machine learning (ML) algorithms can infer cell state and treatment history.

AZ has already deployed several of these systems across its sites around the world. One of the company’s high-throughput platforms, equipped with a 20× brightfield camera, maintains the speed and fluorescence capacity of a conventional cytometer while recording thousands of brightfield images per second. This, he explained, allows the company to study complex cell cultures, such as epithelial layers, that simulate tissue architecture.

In a typical assay, conventional fluorescence markers first define the broad population of interest, for instance epithelial cells expressing ‘epithelial cell adhesion molecule’. The software then extracts single-cell images for that population, which feed into AI models that classify cell types and quantify morphology. The aim is to replace labour-intensive multi-marker staining with quantitative information derived from cell shape, texture and internal structure.

This approach has already enabled researchers to distinguish subtle subpopulations that would have appeared identical using standard one-dimensional parameters. Currently, AI assists primarily in population identification and in substituting image-based descriptors for conventional markers. The next step is to train models to describe how drugs reshape morphology and texture, thereby using imaging itself as the phenotypic readout for screening.

The second major example in the presentation concerned T-cell activation and cytotoxicity assays, central to AZ’s work on cell therapy and T-cell engager platforms. Traditional assays, which rely on panels of activation markers such as CD25 and CD69, reduce a continuum of cell states to a binary ‘on-off’ view. Dr Cimbro noted that this simplification has concealed meaningful biological diversity.

To capture these nuances, AZ has begun to build an image-based reference atlas of T-cell phenotypes. In the coming year AZ intends to process around 100,000 samples which will be tested under controlled conditions with known biological outputs. Each dataset will include images and limited standard parameters to train a foundational model linking morphology to functional outcome.

Once established, the model will allow researchers to position the effect of any novel compound within a known response landscape. Proof-of-concept results have already shown that image-derived features alone can distinguish resting from activated cells and generate accurate dose–response curves without the need for activation markers.

The presentation then moved to AZ’s discovery platform, a high-end spectral flow cytometer capable of both fluorescence and imaging acquisition. This instrument, fitted with 78 detectors and five lasers, can record more than 50 fluorescence parameters while capturing brightfield and fluorescence images at 10,000 to 15,000 events per second. The system can also apply image-derived parameters in real time to gate and sort cells based on nuclear translocation, organelle shape or cell–cell interaction.

One of the most powerful applications involves tracking the nuclear translocation of the transcription factor NF-κB p65, a key regulator of inflammation. Conventional cytometry detects only the overall fluorescence of p65, but imaging cytometry measures how much of the signal overlaps with the nucleus. In unstimulated cells, p65 remains in the cytoplasm; after stimulation, it accumulates within the nucleus. Cimbro explained that AZ has used this approach to screen compounds that influence inflammatory signalling in both primary and immortalised cell types.

He went on to describe the application of imaging cytometry to the study of cellular senescence. Traditional flow cytometry can detect the proportion of senescent cells but provides no information on how senescence progresses. Imaging analysis reveals that senescent cells grow larger and show distinct nuclear as well as cytoplasmic changes. By extracting numerous image-based features, AZ’s researchers have clustered cells into more than 30 subtypes that appear to represent different stages of senescence. These can then be isolated for downstream molecular analysis – a capability not previously available.

Mitochondrial assays have also benefited from the technique. Using fluorescent dyes that indicate membrane potential and mitochondrial mass, the team found that imaging data exposed previously unrecognised heterogeneity. Distinct mitochondrial morphologies and distributions correlated with memory-like and effector-like T-cell subsets, providing an unexpected degree of resolution in functional profiling.

A major conceptual shift has arisen in how imaging cytometry handles cell–cell interactions. Conventional practice discards doublets or aggregates as artefacts. Imaging cytometry reverses that logic by isolating and analysing them. In one study, AZ scientists examined how engineered effector cells interact with tumour targets under different conditions, including the presence of cytokine-sensitive and cytokine-insensitive receptor mutants. The imaging approach allowed the team to quantify 30,000 interacting pairs per condition and to link interaction stability with receptor expression, providing data at a scale that legacy microscopy could not achieve.

Cimbro described a general workflow that now supports many AZ programmes with high-throughput imaging cytometers serve as the primary screening tool, capable of processing a 96-well plate within an hour and scaling to larger formats. Once an assay of interest or a rare population emerges, the team transfers it to a sort-capable imaging cytometer to isolate specific states or interactions. These sorted populations then move to high-content microscopy for detailed live-cell and tissue analysis. Imaging flow cytometry thus forms a bridge between bulk screening and traditional microscopy.

In his concluding words, Cimbro discussed label-free systems that use patterned illumination to record light-scattering profiles as each cell passes through the beam. ML models interpret these optical ‘fingerprints’ to classify cells without fluorescence. Supervised algorithms use minimal standard parameters to define populations before refining them through image features, whereas unsupervised models infer structure directly from the data. The instruments can also sort cells at several hundred events per second.

AZ has already applied this label-free technology to isolate a rare cell population from a mouse model without using genetic or antibody labels. By training the system on scattering patterns characteristic of the target niche, the team successfully extracted and analysed the desired cells, demonstrating how such instruments could one day handle clinical samples rapidly and – significantly – non-destructively.

“The technology is moving from specialist capability to standard equipment. With better data handling and AI, imaging flow cytometry now provides spatial resolution, localisation and dynamic information that classical cytometry never could,” Dr Cimbro said in closing.

Digital Edition

Lab Asia Dec 2025

December 2025

Chromatography Articles- Cutting-edge sample preparation tools help laboratories to stay ahead of the curveMass Spectrometry & Spectroscopy Articles- Unlocking the complexity of metabolomics: Pushi...

View all digital editions

Events

Jan 21 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 28 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 29 2026 New Delhi, India

Feb 07 2026 Boston, MA, USA

Asia Pharma Expo/Asia Lab Expo

Feb 12 2026 Dhaka, Bangladesh