Research news

Gut microbiome has been shown to shape brain function across primate species

Jan 07 2026

Northwestern University research has provided direct experimental evidence that gut microbes influence brain function and gene expression, offering fresh insight into the evolutionary pressures that have shaped large mammalian brains

A study from Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois, USA, has reported that the gut microbiome plays a direct role in shaping how the brain functions, with implications for the evolution of large brains in primates and for the biological origins of some neurodevelopmental conditions. The research has provided the first empirical evidence that differences in gut microbial communities can alter brain gene expression in ways that mirror differences observed between primate species with contrasting relative brain sizes.

Humans possess the largest relative brain size of any primate, yet the evolutionary mechanisms that have enabled mammals to meet the intense energetic demands of brain growth and long-term maintenance remain incompletely understood. Large brains require substantial and sustained energy input and identifying how this requirement has been met during evolution represents a central challenge in evolutionary biology. The Northwestern team has addressed this question by focusing on the gut microbiome as a potential driver of metabolic and neurological change.

“Our study shows that microbes are acting on traits that are relevant to our understanding of evolution, and particularly the evolution of human brains,” said Associate Professor Katie Amato whose field of study is biological anthropology and was the principal investigator of the study.

The research has built on earlier work from Amato’s laboratory which had demonstrated that gut microbes from larger-brained primates, when transplanted into germ-free mice, produced more metabolic energy within the host microbiome. That increased energy output was identified as a prerequisite for the development and function of energetically costly brains. In the latest study, the researchers extended this approach to examine whether microbial differences also altered brain function directly.

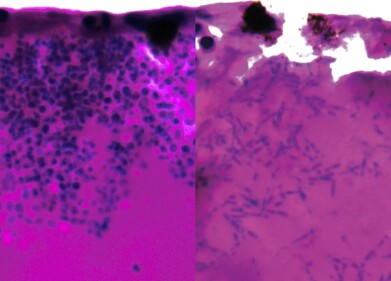

To address this question, the team conducted a controlled laboratory experiment in which gut microbes from two large-brained primate species, humans and squirrel monkeys, and from one smaller-brained primate species – the macaque – were introduced into microbe-free mice. This design allowed the researchers to isolate the effects of microbial composition from genetic and environmental factors that normally complicate studies of brain evolution.

Within eight weeks of altering the mice’s microbiomes, clear differences in brain function emerged. The brains of mice colonised with microbes from smaller-brained primates functioned differently from those of mice that received microbes from larger-brained primates. Detailed analysis revealed that mice harbouring microbes from large-brained primates showed increased expression of genes linked to energy production and synaptic plasticity, the cellular process that underpins learning and memory in the brain. In contrast, mice that received microbes from smaller-brained primates showed reduced expression of these pathways.

“What was super interesting is we were able to compare data we had from the brains of the host mice with data from actual macaque and human brains and – to our surprise – many of the patterns we saw in brain gene expression of the mice were the same patterns seen in the actual primates themselves,” Amato said.

“In other words, we were able to make the brains of mice look like the brains of the actual primates the microbes came from,” she added.

The researchers also identified an unexpected pattern in the mice that received microbes from smaller-brained primates. In these animals, the team observed changes in gene expression associated with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and autism.

Previous studies have reported correlations between gut microbiome composition and conditions such as autism, but direct evidence that gut microbes contribute causally to these disorders has remained limited.

“This study provides more evidence that microbes may causally contribute to these disorders – specifically, the gut microbiome is shaping brain function during development,” said Amato.

“Based on our findings, we can speculate that if the human brain is exposed to the actions of the ‘wrong’ microbes, its development will change, and we will see symptoms of these disorders.

“If you do not receive exposure to the ‘right’ human microbes early in life, your brain may work differently, and this may lead to symptoms of these conditions,” she concluded.

Amato emphasised that the findings open the door to further research into the evolutionary and developmental origins of psychological and neurodevelopmental disorders. She argues that an evolutionary perspective on the interaction between microbes and the brain may help to identify underlying biological rules that govern brain development across species and individuals. Such insights could eventually inform clinical research by clarifying how microbial influences during early life shape brain physiology and long-term neurological outcomes.

For further reading please visit: 10.1073/pnas.2426232122

Digital Edition

Lab Asia Dec 2025

December 2025

Chromatography Articles- Cutting-edge sample preparation tools help laboratories to stay ahead of the curveMass Spectrometry & Spectroscopy Articles- Unlocking the complexity of metabolomics: Pushi...

View all digital editions

Events

Jan 21 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 28 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 29 2026 New Delhi, India

Feb 07 2026 Boston, MA, USA

Asia Pharma Expo/Asia Lab Expo

Feb 12 2026 Dhaka, Bangladesh