Laboratory events news

ELRIG 2025: Crick Institute showcases high dimensional spectral and mass cytometry capability

Dec 12 2025

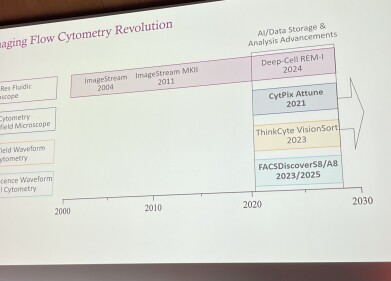

The Francis Crick Institute’s flow cytometry core has shown at ELRIG 2025 how a heterogeneous fleet of spectral, mass and imaging instruments, combined with deep in-house expertise, has enabled ambitious high dimensional biology

Dr Philip Hobson, deputy head of flow cytometry at The Francis Crick Institute, in St Pancras, London speaking at ELRIG 2025 at the GSK campus in Stevenage, showed how an academic core facility can support high-dimensional cytometry in practice. Hobson spoke not as an investigator but as a leader whose role is to enable other people’s experiments, so centred his talk on instrumentation-use strategy, user behaviour, training and the balance between powerful commercial systems and the technical freedom that older, more configurable machines still can offer.

The Francis Crick Institute – which arose from the mergers of the Medical Research Council’s National Institute for Medical Research at Mill Hill and Cancer Research UK’s London Research Institute based between Lincoln’s Inn Fields and Clare Hall – now occupies a single purpose-built facility in central London and employs 1,500 people. Its research spans cancer, infection biology and diverse modelling systems from yeast to mice.

Hobson described his interest in high-dimensional approaches with a background in these technologies even before the Crick acquired its CyTOF mass cytometry system. His remit now covers high-dimensional flow cytometry, high-dimensional imaging and conventional assays with responsibility for high-containment activity, where the facility sorts infectious material under strict biosafety conditions. He also leads on training provision.

Hobson expanded on the organisation’s decision to maintain a heterogeneous instrument fleet rather than standardise to a single platform. The facility uses conventional fluorescence analysers from several manufacturers, spectral flow cytometers from at least two vendors, imaging flow cytometers, a CyTOF-type mass cytometer and a Hyperion system for imaging mass cytometry.

On the sorting side, the core operates multiple droplet sorters from different generations, including jet-in-air instruments alongside more contemporary cuvette-based sorters. Some legacy platforms no longer have commercial support, so the core has taken responsibility for their maintenance to preserve capabilities that newer systems do not fully replace.

One recent strategic purchase has been a large-particle sorter for organoids and complex three-dimensional cultures. As these tissue-like models have become more common at the Crick, demand has grown for a sorter that can handle large, fragile structures rather than simple single-cell suspensions, which shows how the facility tries to anticipate future requirements rather than wait until demand exceeds capacity.

This diversity of instrumentation gives substantial flexibility. Different machines suit different biological questions: jet-in-air sorters can provide high purity or unusual collection modes; some analysers excel at low-signal work, while others prioritise throughput or simplicity for novice users.

The trade-off is the training load. Staff must understand and support every platform, and they must train users for all of them. Hobson noted that if the core was a ‘monoculture’ built around a single instrument family, training would be far simpler. But instead, staff juggle instrument support, method development, high containment responsibilities and data analysis while also teaching external users how to operate and interpret each system.

“The definition of high dimensional is one more parameter than you are comfortable with,” said Hobson, speaking to the elusive notion of ‘high-dimensional’ flow and quoting a colleague.

“High dimensionality is therefore relative. For some users, a move from two to three colours feels daunting, whereas others already run twenty-parameter panels and plan to add more. In a core facility, this matters because high-dimensional experiments consume a disproportionate amount of staff effort although they form a minority of total usage,” he added.

In a typical year, the Crick hosts about 120 research groups with around 105 of them using the flow cytometry platform. Most activity involves mouse models, but human material, stem-cell projects and infection studies also rely on it.

Despite this diversity, most day-to-day flow cytometry at the Crick remains low dimensional. Many users need a straightforward fluorescent protein such as GFP or mCherry plus a viability dye or a simple cell-cycle measurement. Modest panels meet these challenges efficiently, while a small fraction of user groups move into high parameter space with twenty or more markers. Hobson stressed that these high-dimensional users, while only a few, account for a large share of the facility’s instrument time and support.

He then contrasted mass cytometry with fluorescence-based approaches. The Crick has used mass cytometry since 2017. Mass cytometry uses antibodies conjugated to heavy metal isotopes rather than fluorochromes, and an inductively-coupled plasma with time-of-flight mass spectrometry reads their isotopic signatures.

Panel design for mass cytometry can be simpler than for fluorescence because signal overlap arises mainly from known isotopic impurities and suppliers provide spillover information. At the same time, throughput remains lower than conventional flow, acquisition takes longer and sample costs are higher. Researchers who have built large fluorescent antibody collections often need to purchase a novel set of metal-conjugated reagents for a CyTOF experiment which is sometimes difficult to achieve when budgets are restrictive, and platforms require materials from only a small number of specialist suppliers.

Despite these constraints, Hobson highlighted key strengths of the technology. Lyophilised antibody panels in tube format, where a defined cocktail arrives pre-aliquoted and users simply add cells, have proved an attractive option for clinical immune-monitoring studies. Hobson said that he would like to see equivalent ready-to-use, high-parameter panels for fluorescence cytometry to support longitudinal and multicentre comparisons with less variability.

Imaging mass cytometry forms a second major pillar of the Institute’s services and work. Hyperion-type systems stain tissue sections with metal-conjugated antibodies and use a focused laser to ablate tissue pixel by pixel. Each ablated spot yields a mass spectrum from which the instrument reconstructs multiplexed images without auto-fluorescence. The method is relatively slow but enables highly multiplexed imaging.

Hobson acknowledged the infrastructure cost and slower acquisition rates in comparison with conventional microscopy and flow cytometry, but he stressed that the technology continues to evolve. More recent configurations have improved sensitivity and event rates for suspension work.

An early showcase project at the Crick used imaging mass cytometry to examine Lewis lung carcinoma tumours under KRAS inhibition and to characterise immune infiltrates within those lesions. This demonstrated that high-dimensional imaging can reveal complex tissue architecture and cell–cell interactions beyond the reach of conventional immunohistochemistry. The Crick has since integrated imaging mass cytometry with high-plex fluorescence imaging and spatial transcriptomics in multi-modal spatial studies.

On the spectral flow side, the facility runs several spectral analysers and has tested additional systems on loan. Hobson stated that the team does not try to favour a single ‘winner’ among vendors but instead assesses how quickly and reliably it can implement a standard multi-colour panel on each platform. In practice, panels will not often transfer cleanly between spectral instruments as each system has distinct optics, detectors and software, requiring staff to invest time in panel redesign, optimisation and user training.

Training for spectral cytometry usually takes longer than for conventional flow systems. Users must understand unmixing, fluorochrome spectra and the pitfalls of auto-fluorescence subtraction. Hobson reported frequent troubleshooting around unmixing artefacts and issues with auto-fluorescent populations that interfere with panel design.

At the same time, he showed that when the system works well, spectral methods provide notable benefits. In lung experiments, where highly auto-fluorescent alveolar macrophages obscure a GFP-expressing bacterial signal, spectral unmixing that explicitly models auto-fluorescence can reveal a clear positive population that would otherwise remain invisible.

Hobson also underlined the human and educational roles of a core facility. Inside the Crick, his team must train a large but constantly changing user base in flow theory, sample preparation, panel design, acquisition and finally, data analysis. Internally, its staff maintain a deep understanding of instrument physics and under the leadership of head of department Dr. Andrew Riddell, the team retains skills in laser alignment, detector electronics and signal processing and in so doing, do not treat instruments as though they are ‘black boxes’.

This technical commitment linked to one of Hobson’s broader concerns:

“We [as researchers] are getting locked in; we are being told what our science is by what we can actually do on the instrumentation that we have,” he warned.

As instruments have become more integrated and proprietary, core facilities risk a loss of experimental freedom. The ability to modify instruments and add novel detection paths or bespoke optical configurations has diminished as vendors design their systems to prevent intervention by users. At the Crick, the team has kept at least one fully-functional, analogue, legacy cytometer which allows staff to route extra signals and adapt the system for specific assays.

Hobson closed by returning to the wider role of the Crick’s core facility, emphasising what flow cytometry cores can contribute to contemporary biology. At the Crick, they do far more than just keep instruments running but rather curate a diverse technology portfolio, while maintaining niche capabilities, train cohorts of researchers and develop and share analysis pipelines.

Digital Edition

Lab Asia Dec 2025

December 2025

Chromatography Articles- Cutting-edge sample preparation tools help laboratories to stay ahead of the curveMass Spectrometry & Spectroscopy Articles- Unlocking the complexity of metabolomics: Pushi...

View all digital editions

Events

Jan 21 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 28 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 29 2026 New Delhi, India

Feb 07 2026 Boston, MA, USA

Asia Pharma Expo/Asia Lab Expo

Feb 12 2026 Dhaka, Bangladesh