Research news

Low-dose megestrol may boost response to letrozole for oestrogen receptor-positive breast cancer patients

Jan 06 2026

A ‘window of opportunity’ study in post-menopausal patients has reported that adding low-dose megestrol acetate – a progesterone mimic already used to ease hot flushes – has reduced short-term tumour proliferation more than letrozole alone, with similar effects at low and higher doses

A drug that mimics the hormone progesterone shows anti-cancer activity when it accompanies standard anti-oestrogen therapy for women with breast cancer, a Cambridge-led clinical trial has reported.

Investigators assessed low-dose megestrol acetate, a synthetic progestin that clinicians have already used to help patients to manage hot flushes linked to anti-oestrogen breast cancer treatments. The team reported that the same low-dose approach could also exert a direct anti-cancer effect when it accompanied conventional anti-oestrogen therapy.

Around three-quarters of breast cancers are oestrogen receptor-positive. This description indicates that tumour cells carry abundant oestrogen receptors, which can drive cancer growth when oestrogen circulates in the body. Clinicians often prescribe anti-oestrogen treatment for these patients to reduce oestrogen signalling and so inhibit tumour growth. In post-menopausal patients, this approach commonly involves aromatase inhibitors such as letrozole, which lowers oestrogen levels by blocking the enzyme aromatase. However, treatment that reduces oestrogen can cause menopause-like symptoms, including hot flushes, joint and muscle pain and bone loss risk, which can prompt some patients to stop long-term therapy.

The trial was known as PIONEER which stood for A Pre-operative wIndOw study of Letrozole plus PR agonist (Megestrol Acetate) versus Letrozole aloNE in post-menopausal patients with ER-positive breast cancer. It enrolled post-menopausal women with oestrogen receptor-positive breast cancer and compared letrozole alone with letrozole plus megestrol.

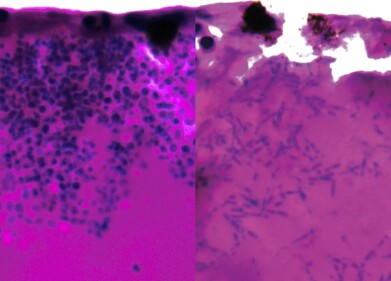

In this ‘window of opportunity’ design, patients received assigned treatment for two weeks before surgery to remove the tumour. The team assessed the proportion of actively dividing tumour cells at baseline and again before surgery as a short-term measure of treatment impact on tumour proliferation.

A total of 198 patients entered the study across ten UK hospitals, including Addenbrooke’s Hospital in Cambridge. Participants received either letrozole alone, letrozole plus 40 mg megestrol daily or letrozole plus 160 mg megestrol daily. After two weeks, patients who received the combination treatment showed a greater fall in tumour growth rates than those who received letrozole alone with the effect appearing comparable at both doses of megestrol.

“On the whole, anti-oestrogens are very good treatments compared with some chemotherapies. They are gentler and patients often take them for many years.

“But some patients experience side effects that affect their quality of life. If you take something long term, even seemingly minor side effects could have a big impact,” said Dr Richard Baird, department of oncology, University of Cambridge and Honorary Consultant Medical Oncologist at Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (CUH).

The researchers linked the clinical findings to earlier laboratory work that explored how progesterone-related signalling interacted with oestrogen receptor biology. Some oestrogen receptor-positive tumours also show high levels of progesterone receptor, another hormone receptor that can influence tumour behaviour. Previous studies have associated progesterone receptor positivity with better responses to endocrine therapy in some settings, although causal mechanisms have remained an active topic of research.

Work led by Professor Jason Carroll at the Cancer Research UK Cambridge Institute used cell cultures and mouse models to test the hypothesis that progesterone could slow division of oestrogen receptor-positive cancer cells by indirectly blocking oestrogen receptor-driven activity. In these models, progesterone slowed tumour growth and the addition of progesterone to anti-oestrogen therapy slowed tumour growth further than anti-oestrogen therapy alone.

“These were very promising lab-based results but we needed to show that this was also the case in patients. There had been concern that hormone replacement therapy, which primarily consisted of oestrogen and synthetic versions of progesterone called progestins, might encourage tumour growth.

“Although we no longer thought this was the case, residual concern had persisted around the use of progesterone and progestins in breast cancer,” said Professor Carroll, who co-leads the Precision Breast Cancer Institute.

To test whether progesterone receptor targeting could complement anti-oestrogen therapy in patients, the investigators selected megestrol – a progestin – and combined it with letrozole. The trial also aimed to inform tolerability considerations because higher-dose megestrol has an established history in oncology but can cause side effects when used for longer periods.

“In the two-week window that we assessed, adding a progestin made the anti-oestrogen treatment more effective at slowing tumour growth.

“It was particularly pleasing to see that even the lower dose had the desired effect,” said Dr Rebecca Burrell of the Cancer Research UK Cambridge Institute and CUH, and a joint first author on the study.

“Although the higher dose was licensed as an anti-cancer treatment, long-term use could cause side effects including weight gain and high blood pressure. But a quarter of the dose was as effective, and this should come with fewer side effects.

“We knew from previous trials that a low dose could help to treat hot flushes in patients who took anti-oestrogen therapy. This could reduce the likelihood that patients stopped medication and so help to improve outcomes.

“Megestrol, the drug we used, was off-patent, which made it a cost-effective option,” Dr Burrell concluded.

Because participants received megestrol for only two weeks, the researchers stated that follow-up studies would need to confirm whether low-dose megestrol would sustain anti-tumour effects over longer periods. Larger cohorts would also help the field to define which patient subgroups benefited most, including the potential role of progesterone receptor levels as a biomarker to guide treatment selection.

The research received funding from Anticancer Fund with additional support from Cancer Research UK, Addenbrooke’s Charitable Trust and the National Institute for Health and Care Research Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre.

For further reading please visit: 10.1038/s43018-025-01087-x

PIONEER: https://cctu.org.uk/portfolio/cancer/trials-open-to-recruitment/pioneer

Digital Edition

Lab Asia Dec 2025

December 2025

Chromatography Articles- Cutting-edge sample preparation tools help laboratories to stay ahead of the curveMass Spectrometry & Spectroscopy Articles- Unlocking the complexity of metabolomics: Pushi...

View all digital editions

Events

Jan 21 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 28 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 29 2026 New Delhi, India

Feb 07 2026 Boston, MA, USA

Asia Pharma Expo/Asia Lab Expo

Feb 12 2026 Dhaka, Bangladesh