-

-

Picture: Cartoon Bacteria. Credit: Balaban Lab

Picture: Cartoon Bacteria. Credit: Balaban Lab

Research news

Study identifies two bacterial shutdown modes that drive antibiotic persistence

Jan 06 2026

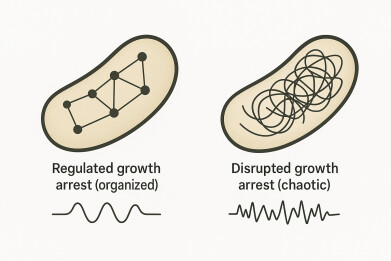

A research team at the Hebrew University has shown that bacteria can survive antibiotic exposure via two distinct growth-arrest states – a regulated dormant programme and a disrupted, vulnerable malfunction

A study from the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, Israel, has reported that bacteria can survive antibiotic treatment via two fundamentally different ‘shutdown modes’, challenging the long-standing assumption that persistence mainly reflects a single dormant state. The researchers described one route as a regulated, protective growth arrest that resembles classical dormancy, while the other reflected a disrupted, dysregulated growth arrest in which cells survived despite widespread cellular malfunction, including impaired membrane stability.

Antibiotic persistence has remained an enduring practical and conceptual problem in infectious disease. In contrast to antibiotic resistance, which arises from heritable genetic changes that allow bacteria to grow in the presence of a drug, persistence allows a small fraction of genetically susceptible cells to survive transient antibiotic exposure. When treatment stops, those survivors can resume growth and seed relapse. Clinicians have long recognised this pattern in recurrent infections, where laboratory testing often shows that the pathogen remains sensitive to the prescribed antibiotic, yet symptoms return after an apparent cure.

The study, led by doctoral candidate Adi Rotem, whose study programme is supervised by Professor Nathalie Balaban, aimed to clarify why different experiments have produced incompatible descriptions of persister cells.

Some studies have painted persisters as metabolically quiet, slow-growing cells that ‘switch off’ and evade drugs that act best on actively dividing bacteria. Other work has reported stress signatures, instability and heterogeneous behaviour that seemed difficult to reconcile with a simple, uniform dormant state. By framing persistence as an umbrella outcome that can arise from more than one physiological condition, the authors argued that both descriptions may have been correct but had simply observed the different underlying states.

“We found that bacteria can survive antibiotics by following two very different paths. Recognising the difference helps to resolve years of conflicting results and points to more effective treatment strategies,” said Professor Balaban.

In the regulated mode, bacteria entered a controlled growth arrest that appeared designed to protect the cell. Many commonly used antibiotics rely – directly or indirectly – on active growth processes to inflict lethal damage. Drugs that disrupt cell-wall synthesis, DNA replication, or protein production often exert their strongest effects when cells attempt to grow and divide. If a bacterium reduces those activities to a minimum, it can become less vulnerable for the duration of exposure, even though it remains genetically susceptible. This regulated state therefore fits the classic dormancy model, although the authors emphasised that it reflected an organised physiological programme rather than a vague ‘sleep’.

In the disrupted mode, bacteria survived in a state that appeared less like protection and more like breakdown. The study reported evidence of dysregulation and physiological instability, particularly in mechanisms that normally maintain cell membrane homeostasis.

Membrane homeostasis refers to the cell’s capacity to preserve the integrity, composition and function of its membrane under stress. If that control fails, the cell can become leaky or structurally fragile. The authors argued that such weakness did not prevent short-term survival under antibiotics but it created vulnerabilities that could become therapeutic targets.

This distinction matters because the same clinical outcome – apparent clearance followed by relapse – could arise from different mixes of persister types. If a patient’s infection contains a large proportion of regulated dormant persisters, then a strategy that relies on prolonged exposure or drug combinations that remain active in low-growth states may prove necessary.

If disrupted persisters dominate, then therapies that exploit membrane instability or other stress-linked weaknesses could offer a route to improve killing without relying solely on conventional growth-dependent mechanisms.

The researchers framed this as a practical path forward for drug development and regimen design. Persistence should be treated as a heterogeneous phenomenon that may require matched interventions rather than a one-size-fits-all approach.

The study also offered a straightforward explanation for why persistence research has produced conflicting results. If different laboratories, growth conditions, antibiotics, or measurement methods preferentially enriched one shutdown mode over the other, then observations of gene expression, metabolism, and cell physiology would vary sharply. Researchers could then reach incompatible conclusions while each described a genuine biological state. The authors suggested that the field has lacked a robust framework to separate these states and has therefore conflated distinct phenomena under a single label.

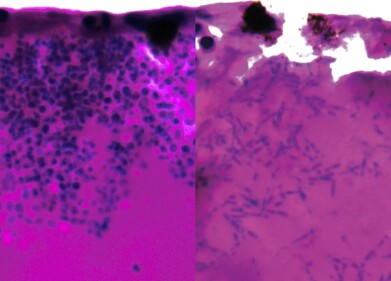

To distinguish the two modes, the team combined mathematical modelling with several experimental approaches that provided complementary windows on bacterial physiology. They used transcriptomics – measuring shifts in gene expression – to infer how cells rewired their internal programmes under antibiotic stress. They also used microcalorimetry to detect tiny heat signals that reflect metabolic activity and to track physiological activity even when growth slowed or stopped.

And they also used microfluidics to observe single bacterial cells under tightly controlled conditions which helped to avoid the averaging effects that could mask clinically important subpopulations.

Together, these tools revealed signatures that separated regulated growth arrest from disrupted growth arrest and highlighted vulnerabilities that appeared specific to the disrupted state.

Antibiotic persistence has contributed to relapsing infections across diverse settings, including chronic urinary tract infection and infections associated with implanted medical devices, where biofilms and fluctuating antibiotic exposure can favour survivor populations.

The study has not implied that dormancy has ceased to matter. Instead, it has suggested that dormancy has represented only one of at least two major routes to survive antibiotic exposure. That shift in framing could help to align competing findings and could support efforts to design therapies that prevent relapse by targeting the right kind of survivor cell at the right time.

For further reading please visit: 10.1126/sciadv.adt6577

Digital Edition

Lab Asia Dec 2025

December 2025

Chromatography Articles- Cutting-edge sample preparation tools help laboratories to stay ahead of the curveMass Spectrometry & Spectroscopy Articles- Unlocking the complexity of metabolomics: Pushi...

View all digital editions

Events

Jan 21 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 28 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 29 2026 New Delhi, India

Feb 07 2026 Boston, MA, USA

Asia Pharma Expo/Asia Lab Expo

Feb 12 2026 Dhaka, Bangladesh