News

Forget all the noise about autism risk, today's medicines regulators may have rejected Tylenol for liver toxicity potential

Oct 29 2025

As scientists in Colorado investigate a potential adjunct therapy to prevent liver injury in Acetaminophen – known as both Paracetamol and Tylenol – overdose toxicologists have reflected on the paradox that one of the world’s most familiar over-the-counter painkillers may struggle to gain the same regulatory approvals if it were introduced today

While social media continues to circulate unsubstantiated claims of links between acetaminophen and neurodevelopmental conditions, researchers are trying to emphasise that there is a real and immediate hazard lying elsewhere. The well-established risk of overdose with this common over-the-counter (OTC) pain and fever remedy has long made acetaminophen – known in the UK as Paracetamol and in the US as Tylenol – a leading cause of drug-related hospitalisation and death.

“Acetaminophen poisoning remains one of the most common causes of emergency room admission linked to non-prescription medicines,” said Professor Kennon Heard, a toxicologist at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus and section chief of medical toxicology within its Department of Emergency Medicine.

“It accounts for tens of thousands of emergency visits each year and is responsible for a large proportion of acute liver failure cases,” he said.

Data from surveillance systems in the US estimate that acetaminophen toxicity leads to around 56,000 emergency department visits and 2,600 hospitalisations each year. Further, it has been implicated in nearly half of all acute liver failures and about one-in-five liver transplants.

Professor Heard, who has published research on acetaminophen toxicity for more than 25 years, is now co-leading a multiyear clinical study that aims to test whether an alternative antidote could protect the liver when treatment is delayed. The trial investigates fomepizole – a drug which has already been licensed for ethylene glycol which is sometimes known as ‘toxic alcohol’, and methanol poisoning – as an adjunct therapy to the standard-of-care acetylcysteine protocol which is currently in use to treat an acetaminophen overdose.

“The University of Colorado and Denver Health, home to the Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Safety Centre, have really been the epicentre of acetaminophen research for the past four decades.

“It is a long tradition of toxicology studies here, and it is a privilege to contribute to that history,” Heard said.

Acetaminophen has been available since the mid-twentieth century and is the active ingredient in Tylenol and numerous store-brand analgesics. It is also present in many other preparations sold for colds, influenza, sinus pain and menstrual discomfort. Its widespread use has reinforced a perception of safety, yet the boundary between therapeutic and toxic doses is perilously narrow.

Heard explained that many overdoses arise not from deliberate self-harm but from misunderstanding dosage instructions.

“There are cases where people accidentally take too much acetaminophen,” he said. “Someone might have a bad toothache and think that if two tablets help, then four must be better, eight even better, and so on.

“Others take repeated doses over several days, which can build up to toxic levels,” he said.

Nonetheless, intentional overdoses remain a major concern.

“The number one rule at any poison centre is that if a substance is available, people will use it,” Heard noted.

“Almost everyone has [medications that include] acetaminophen in their medicine cabinet, which makes it a common agent in self-harm attempts.”

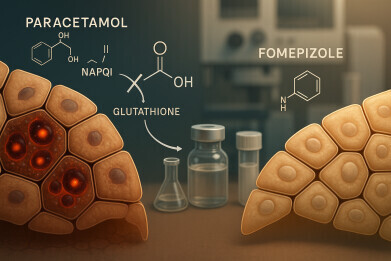

Acetylcysteine has served for decades as the recognised antidote to acetaminophen poisoning, by replenishing depleted glutathione stores in the liver and neutralising toxic metabolites. However, it is most effective if given within eight hours of the acetaminophen ingestion. But many patients do not reach medical care until after hepatic injury has already begun.

“Once liver damage has set in, acetylcysteine becomes much less effective and, in some cases, does not work at all,” Heard said.

The current phase II clinical trial, run jointly by the University of Colorado, in Boulder, and the Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Safety Centre, which is in Denver, is set to test whether fomepizole can extend that treatment window and reduce liver damage. Fomepizole – as an approved antidote for antifreeze poisoning – works by inhibiting alcohol dehydrogenase enzymes that convert ethylene glycol and methanol into harmful metabolites.

The concept of using fomepizole for acetaminophen toxicity dates back to the 1990s.

“There were hints in animal studies and isolated clinical cases that fomepizole might mitigate liver injury in severe acetaminophen toxicity,” he said.

“It inhibits a different enzyme system that contributes to the formation of toxic intermediates. So, there was a plausible rationale, but it had never been tested systematically.”

Recent observational research has found that physicians are increasingly using fomepizole off-label in severe acetaminophen overdoses, particularly where liver failure is imminent. To provide stronger evidence, Heard and his long-time mentor – Professor Richard Dart, director of the Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Safety Centre since 1992 – initiated the controlled clinical trial.

The study randomly assigns patients to receive either the standard acetylcysteine regimen alone or in combination with fomepizole. It is a double-blind design, meaning neither participants nor investigators know which therapy is administered until the trial concludes. Researchers are monitoring biomarkers of liver function to compare the degree of hepatic injury between groups.

Patients are being enrolled at Denver Health, UCHealth University of Colorado Hospital, Children’s Hospital Colorado, and additional partner sites. Recruitment has been slow because strict eligibility criteria limit the number of suitable participants, but the team expects to treat around 40 patients in the study within 18 months. If the interim results suggest a clear benefit, Heard anticipates progressing to a larger, multicentre trial assessing long-term outcomes, including survival or the need for liver transplantation.

“The message I would like people to take away is that acetaminophen is safe only within the recommended limits.

“It is vital to read the label carefully and to be aware that acetaminophen appears in many different products. Taking several medicines at once can easily exceed the daily maximum without realising it,” he said.

Adding that accidental overdose now accounts for almost as many fatalities as intentional self-poisoning: “It is a reminder that familiarity does not equal safety.”

Professor Andrew Monte, another emergency medicine specialist, is collaborating on the study. The researchers believe the work could eventually refine clinical protocols for managing delayed or severe acetaminophen toxicity.

Beyond the clinical context, the research has renewed wider debate about acetaminophen’s regulatory status. The drug’s safety profile, once considered acceptable, would almost certainly face far greater scrutiny if it were to be presented to medicines regulators today as a novel compound. The main issue lies in its narrow therapeutic index: a dose only slightly above the recommended maximum can produce severe liver damage.

In modern regulatory terms, agencies such as the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency in the UK or the US Food and Drug Administration would likely judge such a safety profile incompatible with the unrestricted OTC sale that is true today. Instead, it might be approved only as a prescription medicine and accompanied by stringent risk-management measures and package warnings.

Post-marketing data have shown that acetaminophen toxicity remains a major cause of acute liver failure in Western countries. In the UK, the problem became so acute that in 1998 the government imposed limits on pack sizes – 16 x 500mg tablets – for OTC sales in an effort to curb impulsive overdoses. Non-pharmacy sales also limit purchases to two packets per person. While this policy has led to a reduction in fatalities, it does not address the inherent pharmacological risk.

Toxicologically, acetaminophen’s metabolism via the cytochrome P450 pathway produces a highly reactive intermediate, N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine (NAPQI). Under normal conditions, NAPQI is detoxified through conjugation with glutathione. But when glutathione stores are depleted – for example, through chronic alcohol use, malnutrition or pre-existing liver disease – the toxic metabolite binds to hepatocellular proteins which will trigger cell death. Modern standards under the International Council for Harmonisation would categorise this mechanism as a high-risk metabolic liability.

By comparison with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen, paracetamol’s therapeutic benefit is relatively modest. While NSAIDs can cause gastrointestinal irritation and, at high doses, cardiovascular complications, these risks are usually easier to monitor and manage. Acetaminophen, conversely, can appear benign up to the threshold of toxicity, beyond which liver failure may progress silently and irreversibly.

The ethical and regulatory implications are considerable. For a medicine to qualify for OTC sale, regulators expect a wide margin of safety, predictable effects and minimal risk of serious harm from accidental misuse. Acetaminophen does not comfortably meet those criteria. Although inexpensive and well-tolerated at therapeutic doses, the catastrophic consequences of relatively small overdoses would likely disqualify it from non-prescription status were it introduced today.

Heard’s ongoing research therefore highlights a paradox: society’s dependence on a medicine that would probably struggle to gain modern approval. Yet it also points to scientific progress. If fomepizole can mitigate late-stage toxicity, clinicians could one day manage acetaminophen poisoning more effectively and reduce the burden of liver transplantation.

For now, however, prevention remains the principal safeguard.

“The safest course is to treat acetaminophen with respect. It is effective within its limits, but it is not harmless. Always follow the instructions, and do not assume more is better,” Heard concluded.

Acetaminophen’s endurance as an everyday medicine reflects historical familiarity rather than alignment with the expectations of contemporary pharmacovigilance. In an era of strict safety evaluation, the same compound would likely face significant regulatory pause.

Digital Edition

Lab Asia Dec 2025

December 2025

Chromatography Articles- Cutting-edge sample preparation tools help laboratories to stay ahead of the curveMass Spectrometry & Spectroscopy Articles- Unlocking the complexity of metabolomics: Pushi...

View all digital editions

Events

Jan 21 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 28 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 29 2026 New Delhi, India

Feb 07 2026 Boston, MA, USA

Asia Pharma Expo/Asia Lab Expo

Feb 12 2026 Dhaka, Bangladesh