-

-

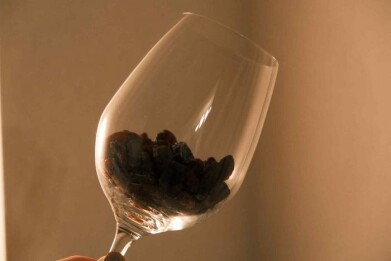

Sun-dried raisins soaked in water will naturally ferment into wine. Credit: KyotoU

Sun-dried raisins soaked in water will naturally ferment into wine. Credit: KyotoU

News

How sun-dried raisins may have helped ancient winemakers turn water into wine

Dec 08 2025

Researchers at Kyoto University have shown that naturally sun-dried raisins can seed fermentation and generate higher ethanol levels than other drying methods which supports the idea that ancient winemakers may have used raisins rather than fresh grapes to produce wine

It is easy to underestimate how inventive early societies were in food and drink production long before the rise of modern science. Prior to the identification of individual microbes, people had already harnessed yeasts such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae to transform simple ingredients into alcoholic beverages. S cerevisiae remains the principal yeast species that drives the fermentation process that generates ethanol. A variety of non-Saccharomyces yeasts can also produce alcohol and contribute distinct taste characteristics but the central role of S cerevisiae in wine production has become a cornerstone of modern oenology.

Contemporary wineries usually add cultured S cerevisiae strains in a controlled way, in order to standardise fermentation and flavour profiles. By contrast, historical assumption has been that ancient wine production was relied on natural fermentation after winemakers had stored crushed grapes in jars and vessels.

However, microbiological research has revealed that S cerevisiae rarely colonises the surface of fresh grape skins in vineyards. That observation has cast doubt on the idea that early winemakers could consistently have produced alcoholic wine by relying on fresh grapes and spontaneous fermentation alone.

A research team at Kyoto University, Japan, has now explored an alternative scenario that places the humble raisin at the centre of ancient winemaking. In an earlier study, the group reported that S cerevisiae appeared in high abundance on the surface of raisins. This finding suggested that dried grapes could have acted as an effective source of alcohol-producing yeast and that ancient producers may have used raisins to inoculate grape must or even plain water.

To test this hypothesis, the scientists collected fresh grapes from an orchard and subjected them to three drying regimes over 28 days. One set dried in an incubator, a second set dried in direct sunlight, and a third set underwent a combination of incubator drying and sun exposure. The team then submerged the resulting raisins in water and stored them in bottles at room temperature for two weeks, with three replicate bottles for each drying method.

This simple protocol was intended to mimic – but in a controlled way – how ancient communities might have added dried fruit to vessels of liquid and waited for fermentation to occur with access to only rudimentary equipment.

The results have provided strong support for the raisin hypothesis. Soaking naturally sun-dried raisins in water proved to be a consistently successful way to generate wine. Only one of the incubator-dried bottles and two of the combination-dried bottles fermented to produce detectable alcohol. In contrast, all three bottles that contained sun-dried raisins underwent fermentation and yielded markedly higher ethanol concentrations than the other groups.

Microbial profiling of the successful samples showed an overall decline in species diversity during fermentation, alongside a rise in the relative abundance of alcohol-producing yeasts such as S cerevisiae. In other words, the community of microorganisms shifted towards a yeast-dominated flora that favours alcohol production.

Taken together, the data suggest that raisins which have dried naturally in the sun can act as a robust reservoir of fermentative yeasts. This, in turn, supports the idea that winemakers in antiquity may have discovered a practical way to ‘turn water into wine’ by adding sun-dried raisins to vessels of liquid.

“By clarifying the natural fermentation mechanism that various microorganisms facilitate at the molecular level, we would like to connect our study to the creation of unique alcoholic beverages,” said first author Dr. Mamoru Hio. The team views this work not only as a window into the past, but also as a route to design novel fermentation processes that could diversify flavour and texture in future drinks.

Although the study has shown that sun-drying strongly favours colonisation by S cerevisiae, the pathway by which these yeasts move from the broader environment onto the grape surface has remained unclear. Wild yeasts can reside in soil, on plant leaves and bark, on insects, and in dust particles in the air. Any of these sources might contribute to the microbial load on drying fruit.

In addition, the researchers noted that their experiments involved a relatively small production scale and that the work took place outside the main regions that supply raisins to the global market. Larger-scale studies in traditional raisin-producing areas with drier climates would provide a closer match to the environmental conditions that ancient winemakers faced.

The team has therefore argued that future research should pay particular attention to low-abundance yeast species that might only be detectable in larger sample sets. These minor components of the microbial community could still influence aroma, mouthfeel and stability in ancient and modern styles of wine. A better understanding of how climatic conditions, drying methods and local ecology shape yeast populations on raisins would also refine reconstructions of early winemaking practices.

“We aim to uncover the molecular mechanism behind this interaction between microbial flora and microorganisms that reside in various fruits, including grapes,” said team leader Dr. Wataru Hashimoto.

“Through natural fermentation, we also hope to develop novel food products and prevent food loss,” he added.

In this context, raisin-based fermentation might offer a route to use surplus or cosmetically imperfect fruit that would otherwise go to waste and hence improve sustainability at this link in the food supply chain.

Hashimoto, however, noted a practical caveat for any reader who may wish to reproduce the method in a domestic setting.

“This [process] only works with naturally sun-dried raisins that are untreated. Most store-bought raisins have an oil coating which prevents fermentation from taking place,” he concluded.

For further reading please visit: 10.1038/s41598-025-23715-3

Digital Edition

Lab Asia Dec 2025

December 2025

Chromatography Articles- Cutting-edge sample preparation tools help laboratories to stay ahead of the curveMass Spectrometry & Spectroscopy Articles- Unlocking the complexity of metabolomics: Pushi...

View all digital editions

Events

Jan 21 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 28 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 29 2026 New Delhi, India

Feb 07 2026 Boston, MA, USA

Asia Pharma Expo/Asia Lab Expo

Feb 12 2026 Dhaka, Bangladesh