Solutions in Science 2025

SinS 2025: PFAS pollution has been significantly underestimated by current monitoring methods: study

Jul 18 2025

“Existing regulatory approaches and analytical techniques are inadequate for the scope and diversity of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) contamination,” asserted Dr David Megson, Reader in Chemistry and Environmental Forensics at Manchester Metropolitan University, during his presentation to the Solutions in Science 2025 conference in Brighton, United Kingdom.

Megson delivered a detailed critique of environmental PFAS monitoring, warning that current detection strategies and regulatory frameworks have failed to reflect the true scale of chemical pollution. He argued that a fundamental shift in analytical methods, surveillance practices and legislation is required to safeguard human and environmental health.

Beginning by dispelling the misconception that PFAS denotes a small group of substances, Megson instead described how PFAS encompasses a vast and structurally diverse class of compounds defined by the presence of at least one fully fluorinated carbon moiety. These include perfluoroalkyl acids, fluorotelomers, perfluoropolyethers, volatile precursors and numerous emerging variants. Many of these compounds remain unregulated, despite widespread use in consumer products, industrial applications and pharmaceuticals.

Megson highlighted the inconsistency of global PFAS regulation. He contrasted the UK’s Environment Agency’s list of 47 priority PFAS with the narrower targets of the US’ Environmental Protection Agency and noted that European Union initiatives to regulate PFAS as a class remain uneven in implementation. In food safety, he observed, the UK continues to monitor only four PFAS routinely.

“Regulatory frameworks do not reflect the reality of PFAS exposure,” he said. “They are only the tip of the iceberg.”

Estimates suggest that more than 4,700 PFAS compounds fall under the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s definition, while the US’ CompTox Chemistry Dashboard lists more than 10,000 substances. Indeed Megson referenced one peer-reviewed study which has extrapolated the number of plausible PFAS structures to be more than 7 million in number.

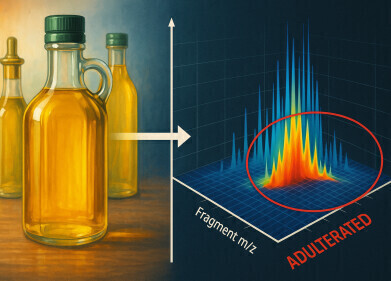

In addressing detection, Megson described the analytical bottleneck facing environmental scientists. The gold standard method – liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry – is limited to a narrow suite of well-characterised PFAS for which reference standards already exist. As a result, thousands of substances remain invisible to routine testing.

To broaden surveillance, researchers have turned to total fluorine-based methods, such as total oxidisable precursor assays, extractable organofluorine, and combustion ion chromatography. These techniques offer a cumulative measure of fluorine content but lack specificity and are prone to under- or overestimation depending on sample preparation and extraction efficiency.

“Not all total PFAS methods are created equal,” Megson cautioned.

His research group has also adopted non-targeted analysis using high-resolution mass spectrometry to detect previously unreported PFAS. This exploratory approach relies on suspect screening, which matches data against known substances, and unknown screening, which infers molecular structures de novo. He applies the Schymanski scale to rank levels of identification confidence, from confirmed structures – Level Level 1 – to exact mass only – Level 5.

In one study near a suspected emission source, his team detected nearly 100 PFAS at Level 4 or above, although very few could be confirmed using commercial reference standards.

Megson’s review of global non-targeted PFAS studies revealed a stark geographical bias. Most have originated from North America, China and Sweden. Not a single non-targeted PFAS study had been conducted in the UK prior to his group’s work. More data exists for parts of Africa than does for the UK, he noted. His review identified more than 40 PFAS classes globally and some studies reported in excess of 600 distinct PFAS in individual environmental samples.

He underscored that the most commonly detected PFAS – including perfluoroalkyl ether carboxylic acids and sulfonic acids – are frequently excluded from regulatory monitoring.

“There is a long tail of rarely detected PFAS that may pose cumulative or delayed risks,” he said.

To demonstrate real-world implications, Megson described a collaborative investigation with The Guardiannewspaper, which examined PFAS pollution in surface water near a chemical facility in the north-west of England. Targeted analysis revealed that several compounds exceeded US environmental thresholds, including for perfluorooctanoic acid. Non-targeted methods identified around 100 additional PFAS, many of which were consistent with industrial sources.

Megson outlined five priorities:

- Regulation must shift from individual substances to class- or subclass-based models to reflect PFAS diversity and environmental persistence.

- Analytical methods must evolve to include total fluorine and non-targeted workflows, with international standardisation and validation.

- Toxicological data must be expanded to support risk assessment for thousands of uncharacterised PFAS.

- Transparency and harmonisation, including open-access databases and consistent reporting metrics, are essential to improve reproducibility.

- The UK must improve its surveillance capabilities, which currently lag behind those of international peer nations.

Megson characterised the PFAS problem as one of the defining environmental challenges of the 21st century, calling for bold, coordinated action to address the analytical, regulatory and health implications of widespread and underreported contamination.

Digital Edition

Lab Asia Dec 2025

December 2025

Chromatography Articles- Cutting-edge sample preparation tools help laboratories to stay ahead of the curveMass Spectrometry & Spectroscopy Articles- Unlocking the complexity of metabolomics: Pushi...

View all digital editions

Events

Jan 21 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 28 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 29 2026 New Delhi, India

Feb 07 2026 Boston, MA, USA

Asia Pharma Expo/Asia Lab Expo

Feb 12 2026 Dhaka, Bangladesh