-

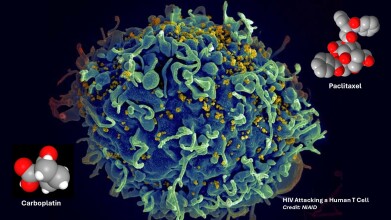

Scanning electron micrograph showing HIV (yellow) attacking a human T cell (blue). In a new study, Johns Hopkins Medicine-led researchers report on a person living with HIV who had a dramatic drop in infected T immune cells after receiving two anticancer drugs (seen as molecular models in the image). Credit: National Institute of Allergies and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health

Scanning electron micrograph showing HIV (yellow) attacking a human T cell (blue). In a new study, Johns Hopkins Medicine-led researchers report on a person living with HIV who had a dramatic drop in infected T immune cells after receiving two anticancer drugs (seen as molecular models in the image). Credit: National Institute of Allergies and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health

Research news

Chemotherapy-linked action on HIV-infected T cell clones points to potential strategy to find a cure for disease

Dec 18 2025

Researchers at Johns Hopkins Medicine have reported evidence that standard chemotherapeutic drugs may selectively suppress HIV-infected immune cell clones, an observation that could inform future strategies to eliminate persistent viral reservoirs without high-risk bone marrow transplantation

Since its identification in 1980s, decades of advances in HIV viral research, development of drug therapies and refining clinical practice have made it possible for people to live with the virus and have long and productive lives. Antiretroviral therapy has been developed which can effectively suppress viral replication to undetectable and non-transmissible levels for as long as treatment continues. However, a definitive cure, with complete eradication of the virus from the body, has remained elusive and has only been documented in a small number of patients who underwent complex and high-risk bone marrow transplantation.

Now, researchers at Johns Hopkins Medicine have reported what they have described as an initial step towards a more practical approach to an HIV cure. In their paper the team described findings from a federally-funded study that focused on a patient living with HIV who underwent chemotherapy for metastatic lung cancer. Following treatment, the patient showed a marked reduction in the number of CD4-positive T lymphocytes that contained an HIV provirus, a form of viral genetic material that plays a central role in the virus’ mechanism to permit long-term persistence in the body.

In people living with HIV, proviruses, which are strands of HIV DNA, typically integrate into the genome of CD4-positive T cells and become a permanent part of the cell’s genetic makeup. This integration allows the provirus to pass to daughter cells when an infected T cell divides, a process known as clonal expansion of HIV-infected T cells. Over time, clonal expansion increases the frequency of infected cells in the body. Proviruses in these daughter cells may remain dormant for long periods or may become active and produce infectious virus, particularly if antiretroviral therapy stops.

CD4-positive T cells – also known as helper T cells – play a central role in immune defence. They recognise pathogens and stimulate antibody production by B lymphocytes, and support CD8-positive T cells – killer T cells – to identify and eliminate infected cells. The persistence of dormant HIV proviruses within this cell population represents one of the main obstacles to viral eradication.

“CD4-positive T cells with dormant HIV proviruses make it difficult to eradicate the virus from the body because the potential is always there for a renewed HIV infection,” said Professor Joel Blankson of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and co-senior author of the study.

“It is vitally important for us to learn why there were significantly fewer clonally expanded, infected CD4-positive T cells in the patient who received chemotherapy.

“If we can understand the mechanism by which that happened, perhaps it can translate into a means to cure HIV,” he added.

Blankson reported that the patient received two chemotherapeutic agents – paclitaxel and carboplatin – as part of treatment for metastatic lung cancer. He explained that the research team suspected HIV-infected CD4-positive T cells may have shown heightened susceptibility to these drugs and therefore failed to proliferate. The study set out to test whether this hypothesis could explain the reduction in infected cell clones observed in the patient.

To investigate the mechanism, the researchers examined an HIV-infected CD4-positive T cell clone isolated from the patient. This clone contained an active, replication-competent provirus integrated into its genome, meaning it retained the ability to infect other T cells. The team stimulated the clone with its cognate peptide, a specific fragment of HIV protein that activates the infected T cell and permits proliferation.

“We treated the stimulated T cells with paclitaxel and carboplatin in one experimental group, and an antiproliferative drug, mycophenolate mofetil, in another experimental group, while we left stimulated clones in the control group untreated.

“The untreated infected clones continued to proliferate but the treated infected ones did not. This was a significant finding, because it suggests a means by which infected cells could be selectively eliminated,” said Blankson.

The researchers emphasised that this phenomenon has so far appeared in T cell clones derived from a single patient. As a result, the team has planned further work to assess whether CD4-positive T cells from other people living with HIV show similar susceptibility to chemotherapy or antiproliferative drugs.

“We suspect the reason that the infected T cell clones we studied were so susceptible to chemotherapy and the antiproliferative drug is because they rely on frequent proliferation to persist in the body,” said Professor Francesco Simonetti, an assistant professor of medicine at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and co-senior author of the study.

“To show this effect in other people living with HIV will provide evidence that this suspicion is correct and, in turn, will direct future research towards HIV cure strategies,” he said.

Simonetti added that a key advantage of this approach lies in its ability to eliminate infected T cells without the need to address multiple other mechanisms that allow HIV to persist in the body. Such strategies could – in principle – complement existing antiretroviral therapy and reduce reliance on high-risk interventions such as bone marrow transplantation.

The authors disclosed that Simonetti has received payments from Gilead Sciences to participate in scientific meetings. Smith was listed as an inventor on a subset of technologies related to the FEST assay described in the paper, has received research support from AbbVie and Bristol-Myers Squibb, and holds founder’s equity in Clasp Therapeutics.

For further reading please visit: 10.1172/JCI197266

Digital Edition

Lab Asia Dec 2025

December 2025

Chromatography Articles- Cutting-edge sample preparation tools help laboratories to stay ahead of the curveMass Spectrometry & Spectroscopy Articles- Unlocking the complexity of metabolomics: Pushi...

View all digital editions

Events

Jan 21 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 28 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 29 2026 New Delhi, India

Feb 07 2026 Boston, MA, USA

Asia Pharma Expo/Asia Lab Expo

Feb 12 2026 Dhaka, Bangladesh