News

Nobel Prize winners unravel how body’s immune system shows restraint

Oct 07 2025

2025 Nobel Prize in

Physiology or Medicine

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine has been awarded to Dr. Mary E. Brunkow, Dr. Fred Ramsdell and Dr. Shimon Sakaguchi for their discoveries that revealed how the immune system prevents itself from attacking the body. Their work on peripheral immune tolerance and the genetic control of regulatory T cells has reshaped the understanding of immune balance and opened the way to novel therapies for cancer, autoimmune disease and organ transplantation.

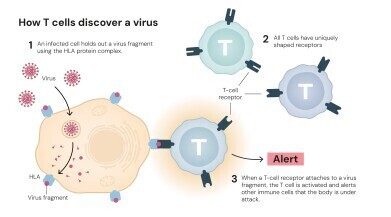

The immune system can be described as an evolutionary masterpiece, protecting the body each day from thousands of invading microbes. Brilliance lies in its ability to distinguish between harmful intruders and the body’s own cells – yet this precision is fragile. When immune regulation fails, it can lead to autoimmune disorders where the body’s defences turn upon itself.

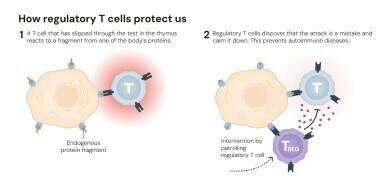

For much of the twentieth century, immunologists believed that immune tolerance was generated mainly in the thymus, the organ where T cells mature. In this view, self-reactive T cells that recognised the body’s own proteins were eliminated there through a process known as ‘central tolerance’. However, this explanation left important questions unresolved. Some self-reactive T cells escaped deletion, and researchers could not explain why autoimmune diseases often developed long after the thymus had completed its task.

The laureates’ discoveries transformed this understanding revealing an additional layer of control – peripheral immune tolerance – that operates outside the thymus and relies on a distinct population of cells called regulatory T cells, or ‘Tregs’. These cells function as the immune system’s security guards, suppressing excessive activity and preventing destructive overreactions. Their identification, and the discovery of the master gene that governs their development – FOXP3 – revolutionised modern immunology.

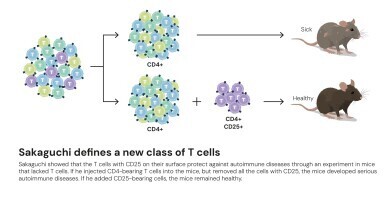

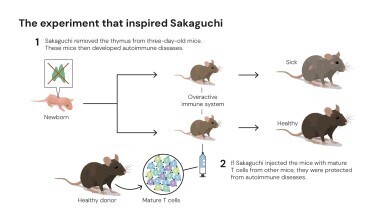

Since the 1970s, the existence of ‘suppressor T cells’ had been proposed which were capable of moderating immune activity. However, inconsistent experimental evidence caused the hypothesis to fall out of favour. But one scientist persisted: Dr Shimon Sakaguchi, working at the Aichi Cancer Center Research Institute in Nagoya, Japan, was intrigued by experiments in which newborn mice, deprived of their thymus, developed severe autoimmune conditions rather than weakened immunity. This paradox suggested that the thymus must produce not only aggressive defender cells but also a second population that restrained them.

To test the idea, Sakaguchi transplanted T cells from healthy mice into thymus-deficient ones and found that the recipients no longer had autoimmune disease. His results indicated that some T cells were actively maintaining immune equilibrium. After more than a decade of investigation, he identified the responsible subset. In 1995, writing in The Journal of Immunology, Sakaguchi demonstrated that these calming cells carried the same surface protein as helper T cells – CD4 – but also expressed another marker, CD25. This dual identity defined an entirely novel class – the regulatory T cell.

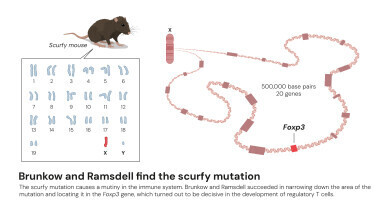

Although many immunologists were unconvinced, definitive genetic evidence soon followed. In the United States, molecular biologists Dr Mary E. Brunkow and Dr Fred Ramsdell were studying an unusual strain of laboratory mice first identified in the 1940s at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, Tennessee – formerly a site which formed part of the research that led to the Manhattan Project.

Male mice from this line, known as ‘scurfy’ mice, developed flaky skin, swollen lymph nodes and enlarged spleens before dying within weeks. The disorder, linked to a mutation on the X chromosome, hinted at a fundamental defect in immune regulation.

By the 1990s, with molecular techniques rapidly advancing, Brunkow and Ramsdell saw an opportunity to uncover the genetic cause. They meticulously mapped the affected region of the X chromosome, narrowing it down to about half a million nucleotides, then comparing twenty candidate genes. The final one proved crucial: an unknown gene resembling members of the ‘forkhead box’ (FOX) family of transcription factors, which regulate other genes during development. They named it FOXP3.

The discovery took on greater significance when the researchers connected the same gene to the human disorder: immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked syndrome (IPEX). Boys with IPEX experience catastrophic autoimmune damage to multiple organs. Brunkow and Ramsdell, working with paediatricians worldwide, sequenced the patients’ DNA and confirmed that harmful mutations in FOXP3 were responsible. Their findings, published in Nature Genetics in 2001, established the first direct link between defective immune regulation in both mice and humans.

Once FOXP3 had been identified, the missing link between Sakaguchi’s regulatory T cells and Brunkow and Ramsdell’s genetic discovery became clear. In 2003, Sakaguchi and colleagues showed that FOXP3 is the master regulator of these cells’ development and function. Without it, T cells fail to acquire the suppressive characteristics that prevent immune self-destruction. This discovery unified decades of conflicting research and founded a new field exploring how immune balance is preserved.

The implications for medicine have been profound. In cancer, tumours exploit regulatory T cells by attracting them into their microenvironment, where they shield malignant cells from immune attack. Researchers now aim to dismantle this barrier by disabling or reprogramming Tregs, enabling the immune system to destroy tumours more effectively. Some modern cancer immunotherapies incorporate strategies to target Tregs selectively.

In contrast, autoimmune diseases such as type 1 diabetes, multiple sclerosis and lupus result from insufficient immune restraint. Here, the therapeutic challenge is to strengthen Treg activity. Clinical trials are underway to assess low-dose interleukin-2, a signalling molecule that promotes Treg growth, in order to restore immune balance. Similar approaches may help prevent organ rejection following transplantation, potentially reducing dependence on toxic immunosuppressant drugs.

Another emerging strategy is to isolate regulatory T cells from a patient’s blood, expand them outside the body, and reinfuse them to restore tolerance. Some laboratories have even engineered these cells with surface antibodies that guide them to specific tissues – such as a transplanted kidney or liver – to protect them from immune attack. These techniques exemplify how fundamental discoveries in immunology can evolve into practical clinical applications.

The careers of the three laureates illustrate the persistence and collaboration required for major breakthroughs. Brunkow, born in 1961 and educated at Princeton University, is now Senior Programme Manager at the Institute for Systems Biology in Seattle. Ramsdell, born in 1960 and a graduate of the University of California, Los Angeles, is Scientific Adviser at Sonoma Biotherapeutics in San Francisco. And Sakaguchi, born in 1951, trained as both physician and scientist at Kyoto University, Japan and now serves as Distinguished Professor at the Immunology Frontier Research Center of Osaka University, in Japan.

Their combined efforts have provided the framework for understanding how the immune system achieves equilibrium – aggressive enough to defeat pathogens yet restrained enough to avoid self-inflicted harm. The 2025 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine therefore recognises a profound conceptual shift. Before their discoveries, the immune system was seen primarily as a force of attack, composed of killer and helper cells that sought to destroy foreign invaders. The Nobel laureates have demonstrated that an internal regulatory force also exists, constantly policing the body to prevent ‘friendly fire’.

Digital Edition

Lab Asia Dec 2025

December 2025

Chromatography Articles- Cutting-edge sample preparation tools help laboratories to stay ahead of the curveMass Spectrometry & Spectroscopy Articles- Unlocking the complexity of metabolomics: Pushi...

View all digital editions

Events

Jan 21 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 28 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 29 2026 New Delhi, India

Feb 07 2026 Boston, MA, USA

Asia Pharma Expo/Asia Lab Expo

Feb 12 2026 Dhaka, Bangladesh