-

Terence Crofts’ research group, including paper co-authors Ezabelle Frank (far left), Terence Crofts (behind the group), Elizabeth Bernate (center, in purple), and Hayden Allman (far right). Credit: University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign

Terence Crofts’ research group, including paper co-authors Ezabelle Frank (far left), Terence Crofts (behind the group), Elizabeth Bernate (center, in purple), and Hayden Allman (far right). Credit: University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign

Research news

Illinois researchers develop method to isolate antibiotic resistance genes in tiny DNA samples

Sep 12 2025

A team of from University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, Illinois, has developed a method to isolate genes from microbial DNA samples so small that 20,000 of them would only weigh as much as a single grain of sugar. In a recent study, they discovered previously unidentified antibiotic resistance (AMR) genes in bacterial DNA taken from human stool samples but also from fish tanks at Chicago’s Shedd Aquarium.

“With AMR on the rise, it’s more important than ever to understand the full diversity of mechanisms bacteria may use to inactivate or avoid antibiotics,” said Dr. Terence Crofts, assistant professor in the Department of Animal Sciences at the College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences.

“If we can get a clearer view of the AMR genes that exist out in the environment, that will give biomedical researchers a chance to look out for them in the clinic and potentially design more effective drugs,” he added.

Crofts created their method – known as METa assembly – to refine a microbiology tool called a functional metagenomic library, which captures bacterial genes from the environment. The technique enables researchers to test for microbial genes in soil, stool, or other samples without the need to culture microbes or sequence entire genomes.

Unlike conventional functional metagenomic libraries, METa assembly requires 100 times less DNA, which makes it suitable for studies where microbes are scarce or where sample collection is limited.

“We used to take the DNA out of the bacteria and just sequence it, but there are so many novel genes in those environments that our sequencing ability has far outstripped our ability to guess at the functions of those genes.

“A lot of these genes have unknown functions, so functional metagenomic screens are a [practical] way to get around that problem,” Crofts said.

Instead of sequencing the DNA directly, the team used an enzyme to cut it into gene-sized fragments before inserting these into Escherichia coli (E. coli) in the laboratory. The bacteria, which grow more readily in laboratory settings than many other microbes, incorporated the DNA into their genetic machinery and displayed the new traits.

Crofts explained that AMR is particularly well-suited for this approach because it is often controlled by a single gene and the result is easy to identify. It is a zero sum situation bacteria either survive or perish when exposed to an antibiotic.

“If E. coli has a resistance gene, it can survive an antibiotic. If it doesn’t, it dies. We might have 10 million E. coli cells in a petri dish with 10 million unique random chunks of environmental DNA.

“If we expose it to a particular antibiotic and only 10 colonies survive, we know those 10 had a resistance gene. Then it becomes very easy to take those colonies and sequence the chunk of DNA they grabbed from that environmental sample,” said Crofts.

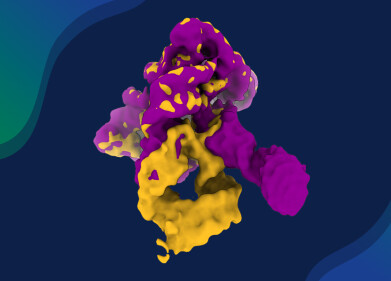

The team has shown that even if sequencing identifies genes for previously unknown proteins, they can be linked directly to AMR and studied further. Using samples from Chicago’s Shedd Aquarium, the researchers identified novel types of efflux pumps – protein channels that expel tetracycline from cells – in tetracycline-resistant sequences.

From the human stool sample, the team found colonies resistant to a class of antibiotics known as streptothricins. Although abandoned in the 1940s due to kidney toxicity, streptothricins have re-emerged as potential candidates for clinical use.

“We found what looks like an entirely new family of streptothricin resistance proteins in our sequences.

“Streptothricin is being brought up as this potentially clinically useful antibiotic, but we should really be trying to find out what resistance is already out there in the environment.

“And instead of making traditional streptothricins less toxic, maybe we should make a next-generation analogue that can beat the AMR mechanisms that may already exist in nature,” he explained.

Crofts has said he intends to extend the METa assembly method to agricultural systems, including soil and livestock samples. He noted that soils, which naturally contain antibiotic-producing bacteria, act as a rich reservoir of resistance genes.

“Agriculture puts all these mammals in close association with this reservoir of AMR genes in the soil. Since we’re giving these animals large amounts of antibiotics it becomes a very ripe environment for resistance to develop and jump into bacteria that can impact our own health,” he concluded.

For further reading please visit: 10.1128/msystems.01039-25

Digital Edition

Lab Asia Dec 2025

December 2025

Chromatography Articles- Cutting-edge sample preparation tools help laboratories to stay ahead of the curveMass Spectrometry & Spectroscopy Articles- Unlocking the complexity of metabolomics: Pushi...

View all digital editions

Events

Jan 21 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 28 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 29 2026 New Delhi, India

Feb 07 2026 Boston, MA, USA

Asia Pharma Expo/Asia Lab Expo

Feb 12 2026 Dhaka, Bangladesh