-

-

“Finding a structural change that explains a specific memory loss in Alzheimer’s is very exciting,” said Harald Sontheimer, PhD, chair of the University of Virginia School of Medicine's Department of Neuroscience and a member of the UVA Brain Institute. “It is a completely new target, and we already have suitable drug candidates in hand.” Credit: University of Virginia School of Medicine

“Finding a structural change that explains a specific memory loss in Alzheimer’s is very exciting,” said Harald Sontheimer, PhD, chair of the University of Virginia School of Medicine's Department of Neuroscience and a member of the UVA Brain Institute. “It is a completely new target, and we already have suitable drug candidates in hand.” Credit: University of Virginia School of Medicine

Research news

Alzheimer’s social memory loss linked to loss of protective nets around neurons

Nov 25 2025

Scientists at the University of Virginia in the United States have shown, in mouse models, that the breakdown of perineuronal nets around brain cells can drive loss of social memory in Alzheimer’s disease, and that matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors may preserve recognition of family and friends

A research team from the University of Virginia (UVA) has identified a specific structural change in the brain that appears to underlie one of the most distressing features of Alzheimer’s disease – the moment when a person no longer recognises family members and close friends. The work, in mouse models, has pointed to a potential way to preserve this form of ‘social memory’ and could open a path towards future therapies that protect patients from this particular loss.

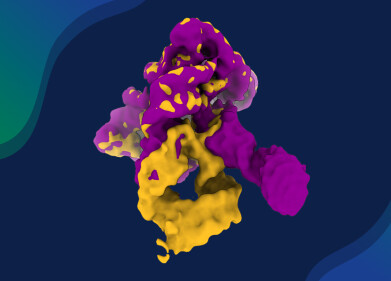

The team, led by Dr. Harald Sontheimer, who is the chair of the Department of Neuroscience at UVA – together with graduate student Lata Chaunsali – focused on specialised extracellular structures known as perineuronal nets. These net-like sheaths surround certain neurons and help stabilise the synaptic connections that underpin specific types of memory. The researchers have shown that when these nets break down, animals lose memories of social encounters, even though their ability to remember objects in their environment remains relatively intact.

Previous work by Sontheimer’s group had already highlighted the importance of perineuronal nets for healthy brain function. These lattice structures wrap around particular inhibitory neurons and act as barriers that regulate which inputs can influence those cells. This regulation helps to maintain precise patterns of neuronal firing that encode and store memories. When the nets remain intact, neurons can continue to participate reliably in the circuits that support learning and recall. When the nets deteriorate, however, those circuits become unstable.

In this study, the researchers studied mice to mimic key aspects of Alzheimer’s pathology. They found that animals with damaged or insufficient perineuronal nets lost the ability to remember other mice that they had met before, a faculty known as social memory. However, the same animals could still learn and recall information about inanimate objects, which indicates that the disruption affected specific memory circuits rather than memory in general. This pattern closely resembled the clinical picture in many people with Alzheimer’s disease, in whom recognition of loved ones often fails before recognition of everyday objects.

“Finding a structural change that explains a specific memory loss in Alzheimer’s is very exciting. It is a completely novel target, and we already have suitable drug candidates in hand,” said Sontheimer, who is also a member of the UVA Brain Institute.

Alzheimer’s disease affects more than 55 million people worldwide, and projections suggest that this figure will rise by more than one-third within the next five years. UVA has established the Harrison Family Translational Research Center in Alzheimer’s and Neurodegenerative Diseases as part of the Paul and Diane Manning Institute of Biotechnology to study the disease. The institute aims to accelerate the development of novel treatments and cures for complex conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease, in which traditional approaches that focus on amyloid plaques and tau tangles have so far delivered only modest clinical benefits.

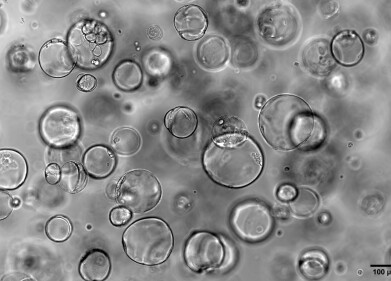

To test whether perineuronal nets could serve as a viable intervention point, Sontheimer and colleagues turned to a class of compounds known as matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) inhibitors. Matrix metalloproteinases are enzymes that can degrade components of the extracellular matrix, including elements of perineuronal nets. MMP inhibitors are already under investigation in oncology and in inflammatory joint disease, because excessive matrix breakdown contributes to tumour spread and tissue damage. The UVA team reasoned that if matrix metalloproteinases mediate the loss of perineuronal nets in Alzheimer’s disease, then inhibition of these enzymes might preserve net integrity and – by extension – social memory.

When the researchers treated Alzheimer’s-model mice with matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors, they observed that the perineuronal nets remained far more intact. Crucially, the treated animals retained their social memory: they continued to distinguish between familiar and unfamiliar mice and to behave in ways that indicated recognition of previous social interactions. The intervention did not simply protect brain tissue in a generalised manner; it appeared to preserve a specific memory system that is highly relevant to the human experience of the disease.

“In Alzheimer’s disease, people have trouble remembering their family and friends due to the loss of a memory known as social memory. We found that the net-like coating known as perineuronal nets protects these social memories.

“In our research with mice, when we kept these brain structures safe early in life, the mice suffering from this disease were better at remembering their social interactions,” Chaunsali said.

“Our research will help us get closer to finding a novel, non-traditional way to treat or better yet prevent Alzheimer’s disease, something that is much needed today,” she added.

The changes observed in the mouse brains appeared to align closely with alterations that neuropathologists have documented in tissue from people with Alzheimer’s disease, which suggests that perineuronal nets may play a similar role in human social memory. That correspondence strengthens the case for perineuronal nets as a translational target, although much work will be necessary before any treatment could reach clinical trials. Researchers will need to establish how best to deliver matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors or related agents to the brain, how early in the disease course intervention would be effective, and whether long-term inhibition of these enzymes is safe.

“Although we have drugs that can delay the loss of perineuronal nets, and thereby delay memory loss in disease, more research needs to be done regarding safety and effectiveness of our approach before this can be considered in humans,” Sontheimer said.

“One of the most interesting aspect of our research is the fact that the loss of perineuronal nets observed in our studies occurred completely independent of amyloid and plaque pathology, adding to the suspicion that those protein aggregates may not be causal of disease,” he added.

If confirmed in further animal studies and in human tissue, the idea that a structural scaffold around neurons helps to safeguard social memory, and that the failure of this scaffold accelerates the loss of recognition, would represent a significant shift in how scientists think about Alzheimer’s disease. Rather than focus solely on the accumulation of misfolded proteins inside or outside cells, future work may place equal emphasis on the integrity of the extracellular architecture that supports neuronal networks.

In practical terms, that could expand the therapeutic landscape to include drugs that stabilise the matrix around vulnerable neurons, protect perineuronal nets from enzymatic attack, or even promote controlled restoration of these structures in patients who already show symptoms.

For families who face the reality of Alzheimer’s disease, the prospect of an intervention that helps maintain recognition of loved ones would not alter every aspect of the condition, but it could preserve a core element of personal identity and relationship.

The UVA team’s findings have not yet reached that stage, and caution remains appropriate. Nevertheless, the identification of perineuronal net loss as a driver of social memory failure in Alzheimer’s disease, independent of amyloid plaques, has added a compelling new dimension to the search for ways to protect the brain from one of the most feared consequences of ageing.

For further reading please visit: 10.1002/alz.70813

Digital Edition

Lab Asia Dec 2025

December 2025

Chromatography Articles- Cutting-edge sample preparation tools help laboratories to stay ahead of the curveMass Spectrometry & Spectroscopy Articles- Unlocking the complexity of metabolomics: Pushi...

View all digital editions

Events

Jan 21 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 28 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 29 2026 New Delhi, India

Feb 07 2026 Boston, MA, USA

Asia Pharma Expo/Asia Lab Expo

Feb 12 2026 Dhaka, Bangladesh