Research news

Vaccine candidate for Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever delivers rapid onset of protection in mice

Dec 04 2025

A virus-like particle vaccine candidate for Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever has shown experimental rapid onset and durable protection, raising hopes for novel coverage where no licensed vaccine exists

Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever (CCHF) is one of the world’s most dangerous yet neglected viral infections with no licensed vaccine or specific antiviral therapy. CCHF virus spreads mainly through infected tick bites or contact with infected livestock and animal blood. It typically presents with sudden high fever and intense malaise and can progress to organ failure and severe internal bleeding. In reported outbreaks, fatality rates reach up to 40 per cent. Endemic transmission has been recorded in parts of Africa, Asia, eastern Europe and the Middle East, and the virus has been recognised as a priority pathogen for pandemic preparedness.

Researchers have now reported promising preclinical results from a vaccine candidate in a mouse model. The international team, which included biomedical scientist Professor Scott Pegan at the University of California, Riverside, has developed a vaccine that uses a non-infectious mimic of CCHF virus to generate rapid and long-lasting immune protection. The candidate has delivered strong protection within days of administration and has maintained antibody responses in animals for extended periods.

Earlier studies by Pegan and others had shown that a single dose of this experimental vaccine could protect animals within three days, an unusually rapid onset of immunity for any vaccine platform. The latest work has now demonstrated that this early protection is not transient but can persist, and that booster dosing can strengthen and stabilise the immune response.

Is the Nipah virus the next emerging pathogen that will cause a pandemic?

Nipah virus (NiV), has shown itself to be an emerging zoonotic virus which may yet have severe human health implications. It has attracted attention due to its high fatality rates and growing poten... Read More

In the new study, the team evaluated how long vaccine-induced immunity lasted in mice after either one or two doses. The animals developed measurable antibody responses that remained detectable for up to 18 months after vaccination, which corresponds to several years of life in humans when comparable lifespan and immune kinetics are considered.

For about nine months, antibody concentrations remained broadly similar in the single-dose and two-dose groups. After that period, animals that received a booster dose showed higher and more stable antibody levels and – on challenge by the live virus – exhibited stronger and more durable protection against disease.

“CCHF is one of those viruses where you can’t simply use the outer coat proteins to make a vaccine,” said Pegan, a professor of biomedical sciences in the University of California, Riverside School of Medicine. Conventional approaches that rely on viral surface glycoproteins have not yet delivered a licensable candidate, in part because of the virus’s complex biology, high pathogenicity and its strict containment conditions required for laboratory work.

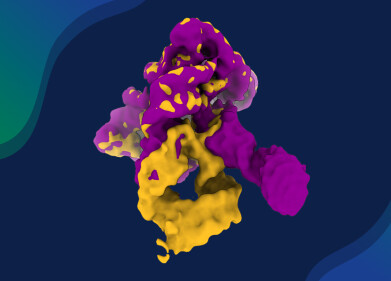

To sidestep these obstacles the group pursued a different strategy. The vaccine uses what is known as a virus-like replicon particle, a construct that resembles the virus in structure and cell entry but – crucially – lacks the genetic material required to complete a replication cycle.

“Made in the lab, this particle can enter cells like a normal virus, but it doesn’t have the genetic material to replicate,” Pegan said.

“That allows the immune system to respond to the virus-like particle without any risk of infection,” he added,

This approach allows researchers to present key viral antigens to the immune system without the hazards associated with handling fully replication-competent CCHF virus.

The choice of antigen has also set this candidate apart from many other viral vaccines. Pegan explained that most licensed vaccines train the immune system to recognise proteins on the outer surface of the virus, since these are the first structures that antibodies encounter when a virus attempts to infect cells. By contrast, this platform focuses on internal viral components, in particular the nucleocapsid, or N, protein, which packages the viral genome and usually remains hidden inside the viral particle.

“Our earlier work showed that the N protein, which is usually hidden inside the virus, turns out to be the key to protective immunity,” he said. That observation has challenged conventional assumptions about which antigens are most useful for protective responses against CCHF virus. And this unconventional focus on the N protein may help explain the unusually rapid onset of protection in vaccinated animals.

“We were amazed to see antibodies appear within just a few days. The rapid response is one reason this platform is succeeding where others haven’t,” Pegan added.

The data suggest that the virus-like replicon particle, with its internal antigen payload, can engage the immune system swiftly and efficiently, perhaps by mimicking key aspects of natural infection without the associated disease.

The evidence for long-term protection has strengthened the case for this candidate as a practical tool for outbreak control. A single dose appears sufficient to deliver meaningful protection in the short term – which would be invaluable in an emergency response situation – for instance for healthcare workers exposed to an outbreak. A booster dose then consolidates this immunity and maintains protective antibody levels for longer periods which could benefit people who live or work in endemic areas where repeated exposures may occur.

“That could be crucial for regions where people might not have easy access to follow-up vaccinations,” Pegan said. In many of the countries where CCHF circulates, health systems already operate under strain, and cold-chain and logistics constraints often limit vaccine deployment. A platform that combines a rapid single-dose response with the option to extend protection through a later booster may therefore offer an attractive balance between practicality and durability.

The team now aims to move the vaccine from laboratory-scale preparation into manufacturing processes that meet regulatory standards. The next stage involves large-scale production under Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) requirements, which govern consistency, purity and quality for products intended for clinical use.

“We can make the vaccine in the lab right now but GMP ensures it can be produced safely, consistently and at scale,” Pegan said.

Beyond CCHF, the virus-like replicon particle platform may provide a more general tool for pathogens that require high containment or that have complex surface antigens.

“Our partners at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) are already exploring this platform for diseases like Nipah virus. It’s a flexible system that could be adapted for a range of emerging pathogens,” Pegan said.

Nipah virus, another high-consequence zoonotic pathogen, has caused outbreaks with high mortality in South and South-East Asia and has also been recognised as a priority disease for research and development. A single, adaptable platform that can incorporate different viral proteins could therefore support rapid vaccine design against multiple threats.

Ultimately, the investigators argue that this candidate has the potential to alter the risk landscape for CCHF, particularly in rural communities where tick exposure is common and where healthcare workers face repeated contact with infected patients and livestock.

“Having something that can protect quickly and last a long time could save lives and change how we respond to outbreaks,” Pegan said. If safety and immunogenicity in humans reflect the encouraging mouse data, health authorities might in future deploy such a vaccine to protect frontline staff, to ring-fence outbreaks, or to immunise high-risk groups, such as abattoir workers and farmers, in endemic regions.

Pegan worked with collaborators from the CDC, the U.S. Department of Agriculture and Auburn University in Alabama. The study received support in part from the CDC and from the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, which forms part of the U.S. National Institutes of Health. The authors noted that the findings and conclusions in the publication do not necessarily represent the official position of the CDC or other funding bodies.

For further reading please visit: 10.1038/s41541-025-01293-9

Digital Edition

Lab Asia Dec 2025

December 2025

Chromatography Articles- Cutting-edge sample preparation tools help laboratories to stay ahead of the curveMass Spectrometry & Spectroscopy Articles- Unlocking the complexity of metabolomics: Pushi...

View all digital editions

Events

Jan 21 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 28 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 29 2026 New Delhi, India

Feb 07 2026 Boston, MA, USA

Asia Pharma Expo/Asia Lab Expo

Feb 12 2026 Dhaka, Bangladesh