Research news

How the cholera bacterium can outsmart a virus

Jun 16 2025

When cholera is mentioned, most people envisage contaminated water supplies and tragic outbreaks in vulnerable regions. Yet behind the scenes, the bacteria responsible for cholera are engaged in a relentless, microscopic conflict — one that may ultimately influence the trajectory of pandemics.

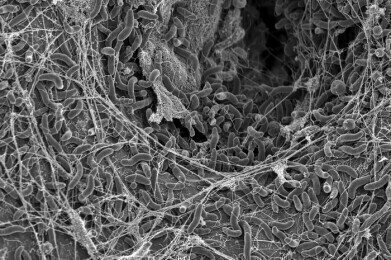

Cholera bacteria are not merely contending with antibiotics and public health interventions — they are also under constant siege by bacteriophages, or phages, which are viruses that infect and destroy bacteria. These viruses influence far more than isolated infections; they can determine the scope and severity of entire epidemics. Certain phages are believed to curtail the spread and duration of cholera outbreaks by targeting and killing Vibrio cholerae, the bacterium that causes the disease.

Since the 1960s, the ongoing seventh cholera pandemic has been driven by what are known as ‘seventh pandemic El Tor’ (7PET) strains of V. cholerae, which have propagated globally in successive waves. In this evolutionary arms race, the bacteria have developed sophisticated mechanisms to resist phage attacks. Many strains carry mobile genetic elements that equip them with anti-viral defences. But why are certain cholera strains particularly adept at evading these viral assaults — and could this ability intensify their impact on human populations?

A significant event in this narrative occurred in the early 1990s, when a cholera epidemic swept through Peru and much of Latin America, infecting over one million people and resulting in thousands of deaths. The causative strains belonged to the West African South American (WASA) lineage of V. cholerae. The reasons for the scale of this outbreak remain only partially understood.

Now, new research by Melanie Blokesch’s group at the Global Health Institute of the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), in France, has shed light on this mystery. The study, published in Nature Microbiology, reveals that the WASA lineage had acquired multiple, distinct bacterial immune systems that protected it from a variety of phages. This enhanced defence may have played a critical role in the extensive spread of the Latin American epidemic.

The researchers analysed Peruvian cholera strains from the 1990s, examining their resistance to key phages, particularly ICP1 — a dominant virus that has been extensively studied in Bangladesh, where it is believed to help limit cholera outbreaks. The Peruvian strains were found to be immune to ICP1, unlike other representative seventh pandemic strains.

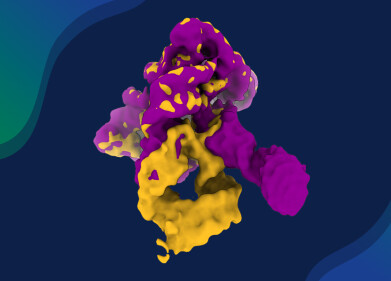

Through gene deletion and transfer experiments, the researchers identified two major genomic regions on the WASA strain that encode anti-phage systems: the WASA-1 prophage and the genomic island known as Vibrio seventh pandemic island II (VSP-II). These regions harbour a suite of specialised defences that together form a robust bacterial immune system capable of warding off phage infections.

One of these systems, known as WonAB, initiates an ‘abortive infection’ response — a self-sacrificial mechanism whereby infected bacterial cells are destroyed before the phages can replicate. This approach differs from classical bacterial immune systems, such as restriction–modification systems, which degrade phage DNA upon entry. “Instead, it stops the phage from replicating but only after it has already hijacked the cholera bacterium’s cellular machinery, effectively locking the infected bacteria in a standoff — but at least the phage doesn’t spread,” explains David Adams, the study’s lead author.

Two additional systems, GrwAB and VcSduA, offer further layers of protection. GrwAB targets phages that use chemically modified DNA to evade detection, while VcSduA defends against other viral families, including another common vibriophage. Together, these systems broaden the bacterial population’s resistance against a spectrum of phage threats.

In essence, the WASA lineage of cholera bacteria possesses an expanded array of anti-phage defence mechanisms, enabling it to withstand both ICP1 and other viral threats.

Understanding how epidemic bacteria resist phage predation is of growing importance, particularly as phage therapy — the use of viruses to combat bacterial infections — gains renewed interest as an alternative to antibiotics. If strains of V. cholerae can gain a transmission advantage through enhanced viral resistance, it could reshape strategies for cholera surveillance, control and treatment. Moreover, it underscores the importance of factoring in phage–bacteria dynamics when studying and managing infectious disease outbreaks.

For further reading please visit: 10.1038/s41564-025-02004-9

Digital Edition

Lab Asia Dec 2025

December 2025

Chromatography Articles- Cutting-edge sample preparation tools help laboratories to stay ahead of the curveMass Spectrometry & Spectroscopy Articles- Unlocking the complexity of metabolomics: Pushi...

View all digital editions

Events

Jan 21 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 28 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 29 2026 New Delhi, India

Feb 07 2026 Boston, MA, USA

Asia Pharma Expo/Asia Lab Expo

Feb 12 2026 Dhaka, Bangladesh