-

-

Adolfo Garcia-Ocaña, Ph.D., City of Hope’s Ruth B. and Robert K. Lanman Chair in Gene Regulation & Drug Discovery Research and chair of the Department of Molecular & Cellular Endocrinology. Credit: City of Hope, Los Angeles

Adolfo Garcia-Ocaña, Ph.D., City of Hope’s Ruth B. and Robert K. Lanman Chair in Gene Regulation & Drug Discovery Research and chair of the Department of Molecular & Cellular Endocrinology. Credit: City of Hope, Los Angeles

Research news

Scientists identify SMOC1 as a driver of beta-to-alpha cell conversion in T2DM

Oct 24 2025

Scientists at City of Hope have identified the gene SMOC1 as a driver of beta-cell dysfunction in type 2 diabetes. The discovery explains how insulin-producing cells begin to mimic glucagon-secreting cells, leading to elevated blood sugar levels and opening a potential route to restore normal insulin production

A research team at City of Hope, Los Angeles – which is one of the leading centres for cancer and metabolic disease research in the United States – has identified a gene that appears to reprogramme pancreatic cells, thereby contributing to the onset and progression of type 2 diabetes (T2DM). The discovery has revealed how the gene known as SMOC1 converts insulin-producing beta cells into glucagon-secreting alpha cells, disrupting the delicate hormonal balance that regulates blood glucose.

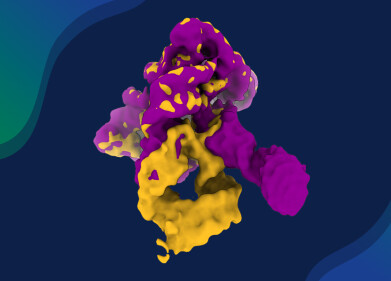

The findings have highlighted SMOC1 as a potential therapeutic target and provided a detailed account of how beta cells lose their identity in T2DM. Pancreatic islets comprise clusters of hormone-secreting cells. Within these clusters, beta cells release insulin to lower blood sugar, while alpha cells release glucagon to raise it. The equilibrium between the two hormones is vital to maintain normal metabolism. In people with T2DM, however, beta cells often malfunction and begin to act like alpha cells, reducing insulin output and exacerbating hyperglycaemia.

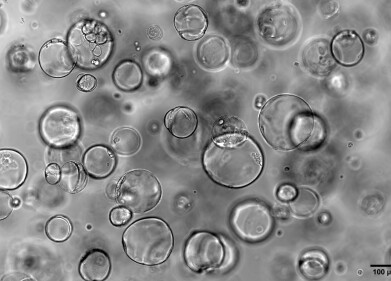

To investigate how this cellular identity shift occurs, the City of Hope scientists performed single-cell RNA sequencing on pancreatic islet samples from 26 individuals, half of whom had T2DM. The analysis allowed the team to classify each cell by its gene expression profile and trace its developmental trajectory over time.

The researchers identified five distinct types of islet cells, each with a unique genetic signature and potential pathway of maturation. In healthy islets, cells could follow branching routes to become either alpha or beta cells, indicating a degree of flexibility. In diabetic islets, this flexibility was lost, beta cells followed a single path that ended with their transformation into alpha-like cells.

“In healthy people, islet cells can mature in different directions – some become more like alpha cells, others like beta cells,” said Dr Adolfo Garcia-Ocaña, who led the study.

“But in T2DM, the path only goes one way: beta cells start imitating alpha cells. This shift may explain why insulin levels drop and glucagon levels rise in people with the disease,” he added.

The team also discovered hybrid ‘AB cells’ that produced both insulin and glucagon, suggesting that these may represent a transitional state capable of developing into either cell type. Among the ten genes linked to this shift, SMOC1 emerged as the principal regulator.

“Normally, SMOC1 is active only in healthy people’s alpha cells,” explained Dr Geming Lu, co-corresponding author of the study.

“But we saw it start showing up in the diabetic beta cells, too. It should not have been there,” he said.

When SMOC1 became active in beta cells, the cells’ insulin-producing machinery slowed, while genes essential to beta-cell identity were silenced. At the same time, markers of immaturity and alpha-cell behaviour increased. These combined effects caused a reduction in circulating insulin and an accompanying rise in blood sugar levels.

“Our results indicate that SMOC1 drives beta-cell dysfunction and the cells’ shift toward an alpha-like state. It helps to explain the fundamental imbalance in hormone production that characterises T2DM,” said Dr Garcia-Ocaña.

The SMOC1 gene has received little attention in diabetes research but the protein it encodes is known to interact with growth factors that promote tissue development and with calcium, which is essential for insulin release. The authors propose that SMOC1 may therefore influence both the differentiation and the function of beta cells.

The implications of this discovery extend far beyond understanding disease progression. By mapping the genetic pathways that underlie beta-cell conversion, researchers can identify potential intervention points to halt or reverse the process. SMOC1 may also serve as a biomarker to detect early dysfunction in beta cells. Moreover, drugs that inhibit SMOC1 activity could preserve insulin production, while regenerative or cell-reprogramming strategies might restore beta-cell populations.

In future work, the City of Hope team intends to determine what causes SMOC1 expression in beta cells, how it can be controlled and what therapeutic agents might block its activity. Their findings mark a significant advance in understanding the molecular roots of T2DM and open the way for treatments that aim to preserve, rather than replace, the body’s own insulin-producing cells.

For further reading please visit: 10.1038/s41467-025-62670-5

Digital Edition

Lab Asia Dec 2025

December 2025

Chromatography Articles- Cutting-edge sample preparation tools help laboratories to stay ahead of the curveMass Spectrometry & Spectroscopy Articles- Unlocking the complexity of metabolomics: Pushi...

View all digital editions

Events

Jan 21 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 28 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 29 2026 New Delhi, India

Feb 07 2026 Boston, MA, USA

Asia Pharma Expo/Asia Lab Expo

Feb 12 2026 Dhaka, Bangladesh