Research news

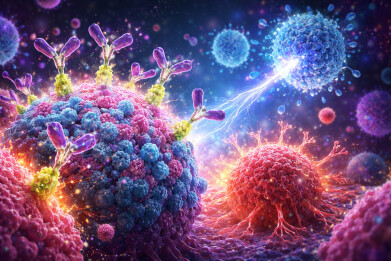

Reprogrammed sugar signals help the immune system to attack cancer cells

Dec 22 2025

Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Stanford University have reported a novel immunotherapy strategy that targets sugar-based immune checkpoints on tumour cells, with the potential to benefit a broader group of cancer patients

A research team drawn from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Stanford University has described a novel approach to cancer immunotherapy that aims to restore immune activity against tumours by blocking sugar-based signals that suppress immune responses. The strategy has focused on reversing a molecular brake that tumour cells use to evade immune attack with encouraging results reported in both laboratory and mouse models.

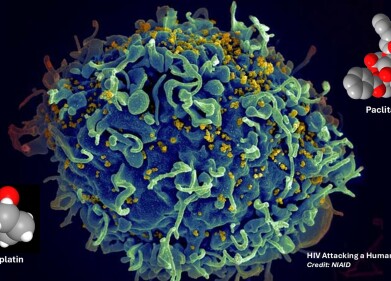

The work has centred on glycans, complex sugar molecules that coat the surface of most cells. Tumour cells frequently express distinctive glycan patterns that dampen immune activity. In particular, many cancers display glycans containing sialic acid, a monosaccharide that can engage inhibitory receptors on immune cells and suppress their activation.

To counter this effect, the researchers have developed a class of multifunctional protein therapeutics termed AbLecs. These molecules combine a lectin, which binds to specific glycans, with an antibody that targets tumour-associated antigens. The design allows lectins to accumulate at the cancer cell surface in sufficient numbers to block immunosuppressive glycan interactions.

“We created a novel kind of protein therapeutic that can block glycan-based immune checkpoints and boost anti-cancer immune responses,” said Professor Jessica Stark, of the departments of biological engineering and chemical engineering at MIT.

“Because glycans are known to restrain the immune response to cancer in multiple tumour types, we suspect our molecules could offer novel and potentially more effective treatment options for many cancer patients.”

Stark, who is also a member of the Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, was lead author of the study with Professor Carolyn Bertozzi, a professor of chemistry at Stanford University and director of the Sarafan ChEM Institute, acting as the study’s senior author.

Cancer immunotherapy seeks to harness the immune system to recognise and eliminate malignant cells. One of the most successful approaches has involved immune checkpoint inhibitors, which block suppressive interactions such as that between programmed cell death protein 1 and programmed death-ligand 1. These drugs have achieved durable remissions in some patients but many individuals have shown limited or no response.

This variability has driven efforts to identify additional immune checkpoints that tumours exploit. One such pathway involves interactions between sialic acid-containing glycans on tumour cells and sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-type lectins – known as Siglecs – on immune cells. When these receptors engage sialic acids, they activate immunosuppressive signalling pathways that inhibit immune cell activation in a manner comparable to established protein-based checkpoints.

“When Siglecs on immune cells bind to sialic acids on cancer cells, it puts the brakes on the immune response. It prevents that immune cell from becoming activated to attack and destroy the cancer cell, just like what happens when programmed cell death protein 1 binds to programmed death-ligand 1,” said Stark.

Despite growing interest in this pathway, no approved therapies have yet targeted the Siglec–sialic acid interaction. Previous attempts have included the use of free lectins to sequester sialic acids but these molecules were found to bind relatively weakly and failed to accumulate at tumour sites in sufficient concentrations for therapeutic effect.

To overcome this limitation, the researchers linked lectins to high-affinity antibodies that specifically recognise cancer cells. This antibody component delivered the lectin domain directly to the tumour surface where it could block sialic acids and prevent engagement with Siglec receptors on immune cells. The result was restoration of immune activity against the tumour.

“This lectin binding domain typically has relatively low affinity, so you cannot use it by itself as a therapeutic. But, when the lectin domain is linked to a high-affinity antibody, you can get it to the cancer cell surface where it can bind and block sialic acids,” said Stark.

In their study, the team designed an AbLec based on trastuzumab, an antibody approved to treat cancers that overexpress human epidermal growth factor receptor 2. One arm of the antibody was replaced with a lectin domain derived from either Siglec-7 or Siglec-9. In cell-based experiments, these AbLecs altered immune cell behaviour and promoted the destruction of cancer cells.

The researchers then evaluated the approach in a mouse model engineered to express human Siglec receptors and human antibody receptors. After injection with cancer cells that formed lung metastases, animals treated with the AbLec developed fewer metastatic lesions than those treated with trastuzumab alone.

Further experiments demonstrated the modular nature of the AbLec platform. The researchers showed that they could substitute trastuzumab with other tumour-targeting antibodies, including rituximab, which targets cluster of differentiation 20, and cetuximab, which targets epidermal growth factor receptor. They also showed that different lectins could be incorporated to block alternative glycan-mediated immunosuppressive pathways.

“AbLecs are really plug-and-play. They’re modular,” said Stark.

“You can imagine swapping out different decoy receptor domains to target different members of the lectin receptor family, and you can also swap out the antibody arm.

“This is important because different cancer types express different antigens, which you can address by changing the antibody target.”

For further reading please visit: 10.1038/s41587-025-02884-6

Digital Edition

Lab Asia Dec 2025

December 2025

Chromatography Articles- Cutting-edge sample preparation tools help laboratories to stay ahead of the curveMass Spectrometry & Spectroscopy Articles- Unlocking the complexity of metabolomics: Pushi...

View all digital editions

Events

Jan 21 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 28 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 29 2026 New Delhi, India

Feb 07 2026 Boston, MA, USA

Asia Pharma Expo/Asia Lab Expo

Feb 12 2026 Dhaka, Bangladesh