Research news

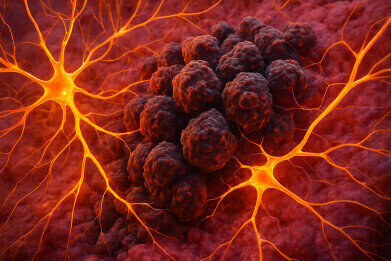

Lung cancer cells in the brain form synapses with neurons to drive tumour growth

Sep 17 2025

Small cell lung cancers that metastasise to the brain have been shown to establish functional electrical connections with neurons, in a discovery that has revealed a novel mechanism by which tumours exploit the central nervous system (CNS) to fuel their progression. The research, led by Stanford Medicine – of Palo Alto, California – has demonstrated that these synapses not only exist but play a central role in promoting the rapid growth of cancer cells.

Although scientists had already established that primary brain cancers could interact directly with neurons, this is the first evidence that small cell lung cancer cells, which originate outside the brain, can integrate into neuronal circuitry once they spread to the CNS. The findings highlight how cancer cells adapt to their environment, co-opting normal cellular processes to their advantage, and has opened the possibility of therapeutic strategies to interrupt such interactions or to repurpose psychiatric or neurological medicines that influence neural activity.

“We have seen metastatic cancer cells near neurons in the brain,” said Professor Michelle Monje, the Milan Gambhir Professor of Paediatric Neuro-Oncology at Stanford Medicine.

“But here, we show that in small cell lung cancer there are direct, bona fide, electrophysiologically functional synapses forming between neurons and cancer cells. And [that] these interactions are central to the cancer cells’ growth. It’s becoming ever clearer that the CNS plays an important role in many types of cancers,” she added.

Professor Monje was joint senior author of the paper with Dr. Humsa Venkatesh, a former postdoctoral scholar in her laboratory who is now Assistant Professor of Neurology at Harvard Medical School, Cambridge, Massachusetts. Stanford’s Dr. Solomiia Savchuk and Kaylee Gentry, MSc., of Harvard Medical School were co-lead authors.

“Understanding the emerging influence of neuronal activity has transformed how we think about brain-derived cancers, and we’re now thrilled to expand this insight to a completely new group of malignancies.

“For the first time, we find that metastatic cancers integrate with neuronal circuitry. This discovery has clear clinical relevance and opens promising new avenues for treatment,” said Dr Venkatesh.

The research builds on earlier work by Professor Julien Sage, Stanford’s Elaine and John Chambers Endowed Professor in Paediatric Cancer, whose laboratory showed in 2023 that small cell lung cancer cells in the brain began to emulate neurons, extending long axons and recruiting astrocytes to secrete protective factors that normally nurture developing neurons.

Monje and Venkatesh’s study has now gone further by demonstrating that cancer cells form genuine synaptic connections that provide them with growth-promoting signals.

“Small cell lung cancer remains one of the most fatal forms of human cancer.

“I am excited about this work because it provides some novel therapeutic directions to inhibit the growth of brain metastases, including molecules that have been used safely in patients with neurological disorders,” said Professor Sage.

Small cell lung cancer accounts for around 15% of all lung cancers and is responsible for more than 200,000 deaths worldwide each year. The disease arises from neuroendocrine cells, which release hormones in response to signals from the nervous system, and retains similarities to both neurons and endocrine cells. At the time of diagnosis, more than half of patients already have metastatic disease, most frequently in the brain.

Professor Monje has spent the past 15 years studying gliomas, including the rare and fatal childhood brain tumour diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. Her work has established the field of cancer neuroscience by demonstrating that neural signalling is a critical driver of brain tumour growth. In the current study, her team investigated how neuronal input affects small cell lung cancer progression both at the site of origin in the lungs and after metastasis to the brain.

Venkatesh and Savchuk used a mouse model developed in Sage’s laboratory to show that cutting off vagus nerve signalling before tumour development had a profound effect: in some cases, no primary lung tumours formed, and none metastasised to the liver. Control animals developed multiple tumours and widespread metastases.

“We saw a profound effect on the tumour burden in the animals from the initiation of the tumour and its spread,” Venkatesh said.

Interfering with vagus nerve activity after tumours had already formed slowed early growth but had little effect on advanced cancers, suggesting that neuronal signals are most important in the initiation and development phases.

The group then investigated the behaviour of human and mouse small cell lung cancer cells implanted into the brains of mice. Tumours that developed near neurons were infiltrated by neuronal processes and grew faster than those further from neuronal input. Biopsies from nine patients with metastatic small cell lung cancer showed the same pattern: neuronal axons were found intermingled with cancer cells, which proliferated more rapidly than cells located in axon-free regions.

To probe the mechanism further, the team applied optogenetics, a technique pioneered by Stanford’s Professor Karl Deisseroth, which uses light to control genetically modified neurons. Stimulating cortical neurons in mice caused implanted lung tumours to grow larger and become more invasive.

“When we stimulated these neurons, the lung cancer placed in the cortex grew much larger and invaded more,” Venkatesh said.

Further analysis showed that part of this growth was due to neuronal secretion of growth factors, but a significant component was mediated directly through functional synapses between neurons and cancer cells.

Culturing the two cell types together in the laboratory revealed that drugs which blocked neuronal electrical activity slowed cancer cell growth. Genes expressed by cancer cells co-cultured with neurons included those involved in synapse formation, and the same signatures were found in patient tumour biopsies. Electron microscopy confirmed that cancer cells participated in synaptic structures, and electrophysiological tests demonstrated that a subset of tumour cells generated electrical currents in response to neuronal signalling. An anti-seizure drug that interfered with synaptic transmission significantly reduced tumour growth in mice compared with controls.

“It’s humbling, as a clinician, to think about all of the ways that the cancer is taking advantage of the patient, and how much of this pathophysiology we have yet to understand,” Monje said.

“The electrical communication that drives this membrane depolarisation is triggering some form of voltage sensitive signalling and promoting growth in a way that as oncologists, we haven’t been thinking about enough. But now we know an important direction we need to pursue to achieve effective therapies for these currently intractable cancers,” she added.

The study received support from Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, and the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

For further reading please visit: 10.1038/s41586-025-09492-z

Digital Edition

Lab Asia Dec 2025

December 2025

Chromatography Articles- Cutting-edge sample preparation tools help laboratories to stay ahead of the curveMass Spectrometry & Spectroscopy Articles- Unlocking the complexity of metabolomics: Pushi...

View all digital editions

Events

Jan 21 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 28 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 29 2026 New Delhi, India

Feb 07 2026 Boston, MA, USA

Asia Pharma Expo/Asia Lab Expo

Feb 12 2026 Dhaka, Bangladesh