Research news

Virus that causes glandular fever is identified as trigger behind lupus disease

Nov 19 2025

A landmark Stanford Medicine study has shown that latent Epstein–Barr virus infection in B cells appears to drive almost all cases of systemic lupus erythematosus, establishing a novel mechanistic link between this common herpesvirus and autoimmune disease and pointing towards future vaccines and Epstein–Barr virus targeted therapies

Stanford Medicine investigators have reported that one of humanity’s most widespread infectious pathogens, the Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) appears to drive almost every case of systemic lupus erythematosus, commonly known simply as Lupus. EBV is a human herpesvirus that infects B lymphocytes and epithelial cells and then usually persists in the body for life in a latent state and is often called ‘glandular fever’. The work has identified a direct chain of causation from latent viral infection in immune cells to a body-wide autoimmune assault on healthy tissues.

Epstein–Barr virus which infects about 95% of adults worldwide, typically persists silently in the body after an initial infection in childhood or adolescence. The Stanford-led team has now shown that EBV can take control of a small subset of immune cells and push them to activate other immune cells on a large scale, so that the immune system begins to attack the body itself.

“This is the single most impactful finding to emerge from my lab in my entire career,” said Dr. William Robinson, both a medical doctor and research PhD holder, who is professor of immunology and rheumatology at Stanford Medicine and senior author of the study.

“We think it applies to 100% of lupus cases,” he said.

The study’s lead author was Dr. Shady Younis, whose research addresses a long-standing suspicion in immunology that EBV plays a central part in lupus but which had previously lacked a definitive mechanistic explanation.

Lupus is a chronic autoimmune disease in which the immune system targets components inside cell nuclei affecting about five million people worldwide. The condition can damage skin, joints, kidneys, heart, nerves and other organs, and symptom patterns may differ widely between individuals. For reasons that remain unclear, about 90% of patients are women.

With timely diagnosis and appropriate medication, many people with lupus can live relatively normal lives. However, about 5% of cases become life-threatening said Robinson who holds the James W. Raitt professorship. Existing treatments can slow disease progression and reduce flares but they do not eradicate the underlying autoimmune process.

EBV is usually transmitted in saliva. Infection often occurs in childhood through everyday contact such as shared cutlery or glasses, or later during adolescence through kissing. The virus can cause infectious mononucleosis, sometimes called ‘the kissing disease’ which typically starts with fever and sore throat, followed by a deep fatigue that may persist for months.

“Practically the only way to not get EBV is to live in a bubble,” Robinson said.

“If you’ve lived a normal life, the odds are nearly 20 to 1 you’ve got it.”

Once a person acquires EBV, the virus embeds its genetic material inside the nuclei of host cells and remains there permanently. EBV belongs to the herpesvirus family, which includes the agents that cause chickenpox and herpes simplex infection. In this latent state, EBV keeps a low profile and evades immune surveillance. Latency may last as long as the infected cell remains alive. Under certain triggers, however, the virus can reactivate and co-opt the cell’s machinery to produce large numbers of viral copies that go on to infect other cells and other people.

Among the cell types in which EBV settles are B lymphocytes – or B cells – a key arm of the adaptive immune system. After B cells encounter pieces of a pathogen, they can perform at least two vital functions. They can produce antibodies, highly specific proteins that recognise and bind foreign molecules known as antigens on microbes that have invaded or threaten to invade the body.

They can also act as so-called professional antigen-presenting cells: they process antigens internally, then display fragments on their surface to alert and stimulate other immune cells to intensify their response. This role effectively amplifies and coordinates an immune attack.

The human body contains hundreds of billions of B cells. Through repeated rounds of cell division and deliberate imprecision in copying the genes that encode antibodies, this population generates an immense range of different antibodies, capable in aggregate of recognising an estimated 10 billion to 100 billion distinct antigen shapes. This diversity underpins our ability to respond to the extraordinary variety of pathogens that can invade the human body.

However, a proportion of B cells – about 20 per cent – are autoreactive. They recognise components of the body’s own tissues rather than external threats. This arises not by design but as a side-effect of the random diversification process that creates antibody variety. Usually, such autoreactive cells remain inert or ‘anergic’, in effect switched off, and do not attack the body.

Autoimmune disease emerges when some of these dormant autoreactive B cells become activated. In lupus, certain activated B cells produce antibodies that bind to proteins and DNA inside cell nuclei. These antinuclear antibodies are the hallmark of the disease. Because nearly all cells contain nuclei, such antibodies can cause tissue damage in many parts of the body, leading to the wide dispersal of symptoms that clinicians observe.

Most people who carry EBV never develop lupus and may be unaware that the virus remains latent in their bodies. However, almost all people with lupus are infected with EBV, as previous epidemiological studies have shown. This correlation has suggested a link for decades, but it has not previously been possible to demonstrate how a small reservoir of latent virus in B cells could precipitate a full-scale autoimmune response.

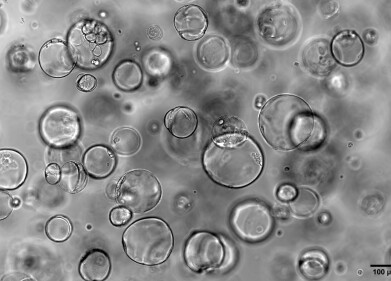

One technical obstacle has been the scarcity of infected cells at any given time. Although latent EBV is nearly universal, it resides in only a tiny fraction of a person’s B cells. Existing methods could not reliably distinguish infected from uninfected B cells within this vast population. Robinson and colleagues addressed this by developing an extremely high-precision sequencing system capable of detecting viral genomes in single B cells.

Using this approach, they found that in a typical EBV-infected but otherwise healthy individual, fewer than one in 10,000 B cells harbours a dormant EBV genome. In contrast, in patients with lupus, about one in 400 B cells carries latent EBV, a 25-fold increase that, according to the authors, has major functional consequences.

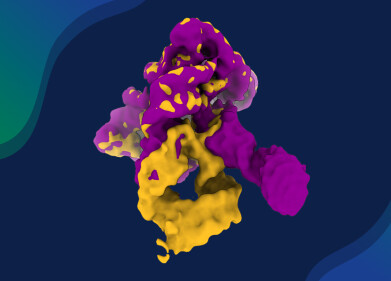

The team combined this EBV-infected-cell detection technology with bioinformatics analyses and cell-culture experiments to uncover how such a small number of infected cells can provoke a strong autoimmune response. They focused on a viral protein called Epstein–Barr virus nuclear antigen 2 (EBNA2). Even in latency, EBV can occasionally induce the infected B cell to produce EBNA2.

The researchers showed that EBNA2 acts as a molecular switch – in genetic terms a transcription factor – that binds to specific locations on the host cell’s DNA and turns on a set of previously silent human genes. At least two of these human genes encode transcription factors that themselves activate many other pro-inflammatory genes. In effect, a single viral protein pushes the B cell towards a highly inflammatory state.

Once in this activated state, the EBV-infected B cell behaves as an especially potent professional antigen-presenting cell. It presents nuclear antigens in a way that preferentially stimulates helper T lymphocytes, or helper T cells, that already tend to recognise nuclear components. These helper T cells, once activated, recruit large numbers of additional antinuclear B cells and cytotoxic ‘killer’ T cells into the response. The result is a substantial barrage of antinuclear immune cells poised to attack.

At that point, it no longer matters whether most of the newly mobilised antinuclear B cells are infected with EBV. The vast majority are not. Nevertheless, if sufficient numbers of them join the response, the outcome is a clinical episode of lupus.

Robinson said he suspects that this EBV-driven cascade of autoreactive B-cell activation may extend beyond lupus to other autoimmune disorders, including multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis and Crohn’s disease, where other researchers have reported hints of EBNA2 activity in relevant immune cells.

If about 95% of people carry latent EBV in their B cells, why does only a minority develop autoimmune diseases such as lupus? Robinson suggested that genetic susceptibility in the host and variation between EBV strains are both likely to play roles. Some viral strains may be especially prone to drive infected B cells into the abnormal antigen-presenting ‘driver’ state that sparks large-scale activation of antinuclear B cells.

Several biopharmaceutical companies are currently developing EBV vaccines, and clinical trials of at least one candidate vaccine are in progress. However, Robinson noted that a preventive vaccine would need to be administered soon after birth to block EBV infection in the first place, since available vaccine strategies cannot clear the virus once it has established latency in host cells.

The work has implications not only for vaccination strategies but also for potential therapies that directly target EBV-infected B cells in patients with established lupus. Stanford University’s Office of Technology Licensing has filed a provisional patent application in relation to intellectual property arising from the study’s findings and from the technologies used. Robinson, Younis and co-author Dr. Mahesh Pandit, a postdoctoral scholar in immunology and rheumatology, are listed as inventors on the application.

The three scientists are co-founders and shareholders of EBVio Incorporated (EBVio Inc.), a company that explores a prospective lupus therapy, ultradeep B-cell depletion. In this experimental procedure, clinicians would eliminate essentially all circulating B cells, which the bone marrow would then replace over several months with fresh B cells that are free of EBV. By uncovering how a latent virus in a tiny fraction of B cells can orchestrate a broad autoimmune attack, the study has provided a mechanistic framework that may guide both preventive vaccination and targeted therapy for lupus and perhaps for other autoimmune conditions that have long puzzled immunologists.

Digital Edition

Lab Asia Dec 2025

December 2025

Chromatography Articles- Cutting-edge sample preparation tools help laboratories to stay ahead of the curveMass Spectrometry & Spectroscopy Articles- Unlocking the complexity of metabolomics: Pushi...

View all digital editions

Events

Jan 21 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 28 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 29 2026 New Delhi, India

Feb 07 2026 Boston, MA, USA

Asia Pharma Expo/Asia Lab Expo

Feb 12 2026 Dhaka, Bangladesh