Abstract

Potential climate tipping points pose a growing risk for societies, and policy is calling for improved anticipation of them. Satellite remote sensing can play a unique role in identifying and anticipating tipping phenomena across scales. Where satellite records are too short for temporal early warning of tipping points, complementary spatial indicators can leverage the exceptional spatial-temporal coverage of remotely sensed data to detect changing resilience of vulnerable systems. Combining Earth observation with Earth system models can improve process-based understanding of tipping points, their interactions, and potential tipping cascades. Such fine-resolution sensing can support climate tipping point risk management across scales.

Subject terms: Climate-change impacts, Projection and prediction

Climate change could drive critical parts of the Earth system past tipping points, causing large-scale, abrupt and/or irreversible changes that harm societies. Here, the authors suggest that satellite remote sensing can play a unique role in helping manage these profound risks, by providing improved early warning of tipping points across scales.

Introduction

Climate change could drive some critical parts of the Earth system towards tipping points—triggering a ‘tipping event’ of abrupt and/or irreversible change into a qualitatively different state, self-propelled by strong amplifying feedback1,2. Crossing tipping points—triggering ‘regime shifts’3 or ‘critical transitions’4—may occur in systems across a range of spatial scales, from local ecosystems to sub-continental ‘tipping elements’1,2. Here, we refer to these collectively as tipping systems. The resulting magnitude, abruptness, and/or irreversibility of changes in system function may be particularly challenging for human societies and other species to adapt to, worsening the risks that climate change poses. Passing tipping points can feedback to climate change by e.g., triggering carbon release5, reducing surface albedo6, or altering ocean heat uptake7. Tipping one system can alter the likelihood of tipping another, with a currently poorly quantified risk that tipping can cascade across systems3,8,9 (meaning here that tipping one system makes tipping of another more likely10).

For all these reasons, an improved observational and modelling framework to sense where and when climate tipping points can be triggered, and how tipping systems interact, could have considerable societal value. Remote sensing data can make a unique contribution because of its global coverage at fine temporal and spatial resolution. It has played an increasingly important role in tipping point science. Early identification of tipping elements in the Earth’s climate system1 drew on remotely sensed evidence of accelerating loss of Arctic sea ice11, Antarctic Peninsula ice shelves12, and the Greenland13,14 and Antarctic13,15 ice sheets. Subsequently, remote sensing has provided key evidence on the location and proximity of tipping points in the polar ice sheets16,17, overturning classical assumptions on the pace of their response to climate change, with measurements of ice speedup18, thinning19, and grounding line retreat16,20, proving critical to identifying destabilisation of the West Antarctic ice sheet21 (WAIS). Satellite data has also been used to detect new candidate tipping elements including a strong shift in cloud feedbacks22, to reveal alternative stable states of boreal23,24 and tropical25–27 vegetation, and to track how vegetation resilience varies over space and time28,29.

Resilience is the ability of a system to recover from perturbations, which can be measured as the recovery rate. Resilience declines when approaching a tipping point30 providing potential early warning signals (EWS) due to critical slowing down4 (CSD) of system dynamics. However, resilience can also be lost in the absence of a tipping point31. Hence it is essential to independently identify tipping systems, e.g., using theory and evidence of alternative stable states and/or abrupt shifts in the past32, in spatial data, or in model simulations. Existing work30 proposed a resilience monitoring system for terrestrial ecosystems, irrespective of tipping, whereas here we focus on tipping systems throughout the Earth system. Previously identified tipping systems1,2,32 include the Greenland ice sheet33 (GrIS), the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation34,35 (AMOC), and the Amazon rainforest25. Recently, empirical evidence of resilience loss has been detected in all three29,36,37, which for the Amazon was based on remotely sensed vegetation optical depth38 (VOD). In fast-responding tipping systems, there is a clear opportunity to leverage remote sensing data to look more widely for resilience changes. For slower-responding tipping systems, the relatively short satellite era of ~50 years is insufficient39. However, space-for-time substitution25,26,40 and spatial stability indicators41 can leverage the fine spatial resolution of satellite records to help forewarn of approaching tipping points. Combining Earth observations and models can improve predictions of, e.g., abrupt droughts to avert food security crises42,43, or abrupt loss of ecosystem function and services to inform regional policy-making and land-use planning44.

Here we start by highlighting policy needs for improved and sustained information on climate change tipping points and remote sensing requirements to help address those needs. Then we delve deeper into how remote sensing can help identify potential tipping points, improve resilience monitoring and early warning of tipping events, and assess the potential for tipping systems to interact and possibly cascade. In the outlook, we suggest potential ways forward and future research avenues.

Policy needs

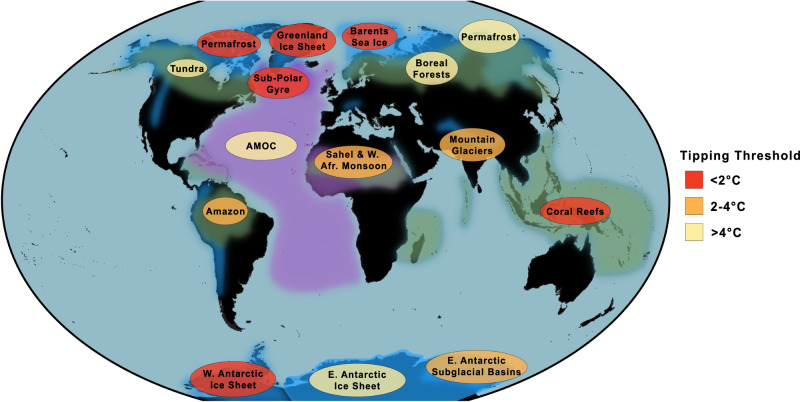

There are strong societal and policy drivers for improved information on potential climate tipping points because abrupt and/or irreversible, large-scale changes pose considerable risks. The risk of crossing a West Antarctic ice sheet tipping point45 has been recognised since the 1970s, and the IPCC’s ‘reasons for concern’ have included ‘large-scale discontinuities in the climate system’ since 2001. Over successive IPCC Reports their likelihood has been repeatedly revised upwards, such that there are now reasons for concern at present levels of global warming46. Figure 1 summarises currently identified climate tipping elements and their estimated sensitivity to global warming2, indicating that several major systems are at risk of being tipped below 2 °C. Considerable uncertainties remain and remote sensing data can help constrain them by, e.g., comparing model results to empirical evidence including identifying emergent constraints47, and estimating proximity to tipping points using CSD applied to remotely sensed data. Overall, interactions between tipping elements, including feedback to global temperature, are assessed to further increase the likelihood of tipping events9,48, although some specific interactions may decrease it48. The desire to avoid crossing climate tipping points has already informed mitigation policy targets including the 2015 Paris Agreement to limit warming to “well below 2 °C” and subsequent ‘net zero’ emissions pledges49. In our view, the risk of tipping was previously underestimated2,46, and this gives a compelling reason to strengthen such mitigation pledges and action to meet them.

Fig. 1. Climate tipping elements and their sensitivity to global warming based on a recent assessment2.

Tipping elements are categorised as cryosphere (blue), biosphere (green), or circulation (purple). Colours of labels denote temperature thresholds categorised into three levels of global warming above pre-industrial (key on the right), with darker red indicating lower temperature thresholds (greater urgency). Permafrost appears twice as some parts are prone to abrupt thaw (at lower temperatures) and some (organic-rich Yedoma) to self-propelling collapse (at higher temperatures).

At national-regional scales, climate tipping points could have severe impacts, such as stronger and more frequent extreme events, accelerated sea-level rise, and fundamental changes in climate variability50. These impacts are often distinct in their pattern and/or magnitude from those expected due to global warming alone, thus posing distinct adaptation challenges. Whether or not tipping points can be avoided by stronger mitigation policy, improved information on where and when they could occur can help guide stronger and more targeted adaptation policy. This can be aimed at reducing impacts of tipping points, exposure, and/or vulnerability to those impacts, and therefore risk51. Where biosphere tipping systems are (at least partly) within a national jurisdiction (e.g., boreal forests, Amazon rainforest, tropical coral reefs), remotely sensed information on an approaching tipping point could help inform national efforts to increase ecosystem resilience30. At local scales, the risk of climate change triggering tipping events, e.g., in ecosystems or glaciers, is a challenge for regional policy and management, which again can benefit from improved risk assessment and resilience monitoring30.

Remote sensing targets and requirements

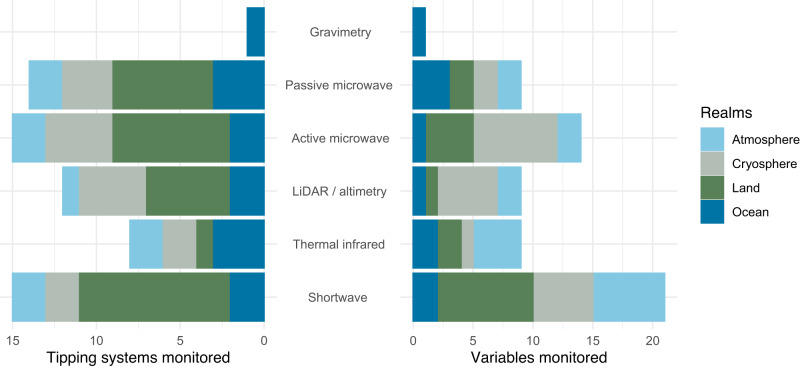

Given these needs, how can remote sensing of tipping systems help support policy-making and environmental management across scales? Table 1 summarises the tipping systems discussed herein, their key properties, the current utility of remote sensing for probing tipping processes, pertinent variables sensed, and methods of remotely sensing them. Figure 2 summarises the capacity of different remote sensing methods to monitor tipping systems and pertinent variables in different domains. Scientific targets for remote sensing of tipping systems include: monitoring relevant feedback processes to improve process understanding52; detecting alternative stable states and associated abrupt changes53; establishing links from alternative states and their stability to climate variables25,26,28; observing system dynamics over time including changes in stability or resilience, and associated early warning signals on regional16,29 and global54 scales, and; calibrating, constraining and evaluating models of tipping systems to improve predictions17,22.

Table 1.

Tipping systems, their properties, and means of remotely sensing them

| Realm | Tipping properties | Remote sensing | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tipping system | Type of tipping | Time-scale of event (yr) | Revers-iblity over 100yr?a | Ref(s) | Current utilityb in probing tipping processes | Properties sensed | Method(s) of sensing | ||||||

| Vis-Shortwavec | Thermal infrared | LiDAR / altimetryd | Active microwave | Passive microwave | Gravimetry | ||||||||

| Ocean circulation | Atlantic Overturning (AMOC) | Macro | ~10–100 | No | 58 | Low |

Sea surface temp. Sea surface salinity Sea level Major currents |

● | ● | ● |

● ● |

● | |

| Sub-Polar Gyre (SPG) | Macro | ~10 | No | 58 | Low | ||||||||

| Ocean biosphere | Pelagic ecosystems | Clustered | ~10 | Maybe | 150,151 | Mid |

Ocean colour Sea surface temp. Sea surface pHe |

● ● |

● ● |

● ● |

|||

| Coral reefs | Clustered | ~10–100 | Maybe | 152,153 | Mid |

Habitat Sea surface temp. Wave height |

● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| Terrestrial biosphere | Amazon forest | Propagating | ~10 | No? | 29,154,155 | High |

Productivity indices Land cover types Vegetation structure |

● ● ● |

● |

● ● |

● | ||

| Boreal forest | Clustered | ~10 | No? | 23,24 | High | ||||||||

| Forests (local) | Impact | ~1–10 | Yes? | 94 | Mid | ||||||||

| Savanna | Clustered | ~10 | Yes | 25,26,113,114 | High | ||||||||

| Patterned veg. | Impact | ~10 | Yes | 68 | Mid | ||||||||

| Tidal marshes | Impact | ~10 | Yes | 156 | Mid |

Productivity indices Water indices |

● ● |

||||||

| Lake ecosystems | Impact | ~1–10 | Yes | 157,158 | Mid | ||||||||

| Peatlands | Impact | ~10–100 | No | 159,160 | Mid |

Water table depth Burned area |

● ● |

● | |||||

| Permafrost soils | Clustered | ~10–100 | No | 58,161 | Low |

Soil propertiesf GHG concentration |

● ● |

● ● |

● | ● | |||

| Atmospheric circulation |

Monsoons (S. America, W. Africa, S. Asia) |

Macro | ~1–10 | Yes | 42,162 | Mid |

Precipitation Land cover change Aerosols Ozone concentration |

● ● ● ● |

● ● |

● ● |

● ● |

● | |

| Blocking events & heatwaves | Impact | ~0.01 | Yes | 42 | Mid |

Land surface temp. Cloud properties |

● |

● ● |

● | ||||

| Cryosphere | Sea ice | Impact | ~1–10 | Yes | 163–165 | High | Area and thickness | ● | ● | ● | |||

| Ice shelves | Macro | <1 | No | 163–165 | Low |

Area and thickness Surface melt |

● | ● |

● ● |

● | |||

| Ice sheets | Macro | ~100–104 | No | 163–165 | Low |

Velocity Surface elevation Grounding line Surface melt |

● | ● |

● ● |

● ● ● |

● | ||

| Mountain glaciers | Impact | ~1–10 | Yes | 165 | Mid |

Extent Snowline Surface elevation Velocity |

● ● ● ● |

● ● |

● ● ● |

||||

a Reversibility is considered on the timescale of a human lifespan. b Utility scale: high = key approach; mid = complementary addition to what is available from in situ data; low = offers monitoring of a process influencing tipping dynamics but insufficient to fully monitor the state of the tipping system. c Includes ultraviolet, visible to short-wavelength infra-red (VSWIR), multi-spectral and hyper-spectral methods. d Includes optical and radar. e Inferred from SST, SSS, chlorophyll. f Inferred from land cover types, land surface temperature and snow dynamics.

Fig. 2. The capacity of different remote sensing methods to monitor tipping systems and pertinent variables.

Summarises information in Table 1 (grouping ocean circulation and ocean biosphere together as the ‘ocean’ realm).

Building on previous work42, we propose a minimum set of ideal criteria for remotely sensed datasets to be useful in tipping point applications: (1) Salient variables correlated with key processes underlying tipping dynamics and their possible interactions. (2) Accurate, analysis-ready data. (3) Spatial coverage of the tipping systems of interest. (4) Spatial resolution sufficient to resolve key feedbacks involved in tipping dynamics. (5) Temporal resolution sufficient to resolve timescales of tipping or recovery (Table 1). (6) Temporal duration sufficient to estimate system resilience, and ideally to detect changes in forcing and resilience. (7) Low data latency to support timely detection and/or early warning of tipping points.

Box 1 expands on current remote sensing capabilities and limitations in relation to these criteria.

Box 1 Remote sensing capabilities and limitations in relation to tipping point criteria.

Current remote sensing has capabilities and limitations in relation to a minimum set of ideal criteria for tipping point applications42:

Salient variables correlated with tipping processes. The increasing diversity of geophysical parameters retrievable from satellites widens capabilities, but established metrics (e.g., normalised vegetation difference index; NDVI) can be limited in their ability to probe variables prone to tipping (e.g., biomass)30. Consistency between remote sensing data records also needs to be more extensively studied145 to reliably link tipping phenomena to climate variables.

Accurate, analysis-ready data. Several operational services make pre-processed, calibrated, and validated datasets available to defined standards, but accuracy and coverage can still be inconsistent in space and time, biasing resilience estimates. Notably optical and thermal infrared data require masking (e.g., for cloud) and correcting for atmospheric attenuation, adding to retrieval uncertainty and making inferences of resilience less reliable91. This is compounded by artefacts introduced by merging and harmonising observations from multiple sensors141 (see Box 2).

Spatial coverage of tipping systems. Polar-orbiting satellites help provide global coverage, but monitoring of below-surface ground and water is limited, restricting sensing of e.g., permafrost or the AMOC. Optical (passive shortwave) measurements are limited by sunlight availability and cloud cover, seasonally restricting sensing of e.g., sea ice, ice sheets, and tropical or boreal forest. Synthetic aperture radar (SAR) data (active microwave) are illumination independent, unaffected by cloud, and can monitor many tipping systems, but have inconsistent coverage due to frequent switching of modes according to user or security interests.

Spatial resolution is sufficient to resolve tipping dynamics. The wide range of very fine resolution (<1 m) and fine resolution (<10 m) satellite constellation missions and sensing types facilitate space-for-time substitution, derivation of spatial stability indicators, and pattern change detection. However, lack of open access to very fine-resolution data, short collection timespans, and computational overheads of data analysis pose challenges, whilst cross-calibration and co-registration of pixels restrict suitable precision for ecological applications.

Temporal resolution is sufficient to resolve timescales of tipping or recovery. Regular revisits (relative to system variability) allow the detection of abrupt changes, and perturbations, and the calculation of temporal resilience indicators (e.g., CSD indicators as proxies of recovery rate). Upscaling techniques using data from geostationary missions with sub-hourly observations and exploiting SAR or passive microwave sensor data (e.g., VOD products), may help fill data gaps due to cloud cover and insufficient revisits, particularly in the tropics.

Temporal duration is sufficient to estimate system resilience. Continuous time series of multi-decadal length for some variables are valuable for identifying acceleration of processes (e.g., ice melt; forest dieback), detection of abrupt shifts, and analysis of changing variability and resilience for potential early warning in fast (e.g., ecological) tipping systems, but are insufficient in slow tipping systems (e.g., AMOC or Greenland ice sheet).

Low data latency to support timely detection and early warning of tipping points. Near-real-time data are now available for many remote sensing products enabling resilience monitoring even for very fast tipping systems42,43. However, latencies are still limited by revisit frequency and the time of overpass, which may bias observations, e.g., to miss peaks in fire coverage, plant water stress, or meteorological extremes.

Remote sensing opportunities

Having established these criteria, we now identify and elaborate key opportunities for remote sensing to advance the understanding and detection of different tipping phenomena, of changing resilience, and of interactions between tipping systems.

Detecting different tipping phenomena

Remote sensing can advance the detection of different types of tipping phenomena across scales (Table 1), which pose different remote sensing challenges and opportunities.

Crossing scales

The most impactful tipping points can be divided into four categories: Impacts can result from tipping inherently large-scale tipping elements (macro tipping), or from localised tipping points that interact to cause larger-scale change (propagating tipping) or are crossed coherently across a large area (clustered tipping) or initiate significant consequences in social systems (societal impact tipping). Large-scale tipping elements have generally been identified1,2 from the ‘top down’, e.g., from conceptual models, understanding of key feedbacks, and/or paleoclimate records of large-scale past abrupt changes32. Meanwhile, localised tipping systems have principally been identified from the ‘bottom up’ by direct observations55,56. Remote sensing can simultaneously identify and monitor tipping systems, phenomena, and their interactions across scales.

Macro tipping

For tipping elements involving atmospheric circulation (e.g., monsoons), ocean circulation (e.g., AMOC, sub-polar gyre; SPG), or ice sheets (e.g., GrIS, WAIS), the crucial reinforcing feedback mechanisms that can propel tipping operate across large spatial scales. The global coverage of remote sensing uniquely enables comprehensive observation at the large scale of those feedbacks. Even where a system is only partially observable, remotely sensed data can reveal underlying (in)stability. For example, remote sensing provides unique opportunities to identify large-scale expressions of SPG and AMOC circulation strength and associated stability changes in fingerprint patterns in sea surface temperature (SST), salinity (SSS), or height (SSH) in specific areas (e.g., Labrador Sea and Nordic Seas) where models suggest a link between these observable fingerprints and proximity to tipping points57. Remote sensing of deep ocean pressure from gravity field changes also reveals below-surface characteristics relating to AMOC strength58. Remote sensing of fine-scale properties across large areas can be used to recalibrate process-based models to improve assessments of large-scale tipping potential. For example, assimilating remotely sensed rainfall data can improve short-term monsoon forecasts59. Correcting modelled cloud ice particle content has revealed the possibility of much higher long-term climate sensitivity22. Furthermore, progress is being made assimilating remotely sensed ice-surface velocity and elevation changes into high-resolution models of Antarctica60.

Propagating tipping

Large-scale tipping elements can in some cases (e.g., WAIS, Amazon rainforest), be considered as networks of smaller, coupled components within which propagating tipping may occur due to causal interactions. In rare cases, tipping of the most sensitive components may ultimately destabilise the rest in a ‘domino cascade’10. The comprehensive coverage of remote sensing at high spatial and temporal resolution is uniquely able to detect propagating tipping by monitoring pertinent localised phenomena and larger-scale responses. For example, several localised tipping points of the Pine Island glacier are theoretically able to destabilise the Amundsen basin61, in turn risking the whole West Antarctic ice sheet62. Satellite-based radar altimetry has detected both the localised grounding line retreat of glaciers16 and confirmed that ice dynamical imbalance has spread to one-quarter of the WAIS since the 1990s19. Another example is the Amazon rainforest, where if dieback starts in the northeast it may propagate southwest—along the prevailing low-level wind and moisture transport direction—through the reduction of rainfall recycling by the forest63. Alternatively, dieback or deforestation starting in the drier southeast may propagate through drying the local climate and enhancing fires. Continuous satellite-based drought42 and fire monitoring are crucial to detect where the forest is at risk of tipping and any propagating tipping. Remote sensing can also track human activities of deforestation, land-use change64, and associated forest fragmentation65 that may trigger tipping. At ecosystem scales, remote sensing can detect propagating tipping, e.g., in the form of propagating ‘invasion fronts’ where one bi-stable ecosystem state replaces another66. It can also monitor potential inhibition of propagating tipping by damping feedback at larger scales, for example in patterned vegetation systems67,68.

Clustered tipping

Where spatial coupling is less strong, localised tipping may still occur in clusters near-synchronously across a large area, due to a spatially coherent climate or anthropogenic forcing reaching a common threshold, e.g., widespread coral bleaching, thermokarst, and lake formation in degrading permafrost, or synchronous forest disturbances69 and dieback. Remote sensing is key to detecting clustered tipping and assessing its spatial scale, for example through the application of abrupt change detection algorithms70—e.g., change point analysis applied to dryland ecosystems53,71 or general trend retrieval applied to thaw lakes across the Arctic72. Remote sensing across environmental gradients is also key to assessing where clustered tipping could occur, helping detect multiple attractors and thus the potential for local tipping points, using e.g., tree cover with respect to rainfall. Early studies suggested widespread multi-stability of tree cover along rainfall gradients in tropical25,26 and boreal23 regions. However, other potential causal drivers of multimodality—notably human activities—can shrink the areas of true bistability24,27,73. Remote sensing of the Global Climate Observing System’s Essential Climate Variables74 (GCOS ECV) can also provide evidence of pertinent feedbacks, e.g., localised forest-cloud feedbacks75 or large-scale alteration of carbon sinks76 (e.g., by permafrost thaw or forest dieback).

Societal impact tipping

Remote sensing can detect localised tipping points in the provision of ecosystem services, which can have substantial impacts on societal systems, where tipping intersects with high human population density. For example, the abrupt loss of glaciers that feed dry-season runoff can have severe impacts on agricultural irrigation downstream77, and agricultural systems may exhibit their own tipping points in the delivery of ecosystem services78. Another example is the amplification of persistent heatwaves by land surface drying and atmospheric heat storage79, with potentially severe impacts—e.g., Europe 2003, Russia 2010, and North America 2021. Remote sensing data are already an essential part of ensemble forecasting of atmospheric blocking events and helped detect amplifying feedbacks and resultant impacts on the biosphere80, including wildfires81, affecting air pollution and human health82. Remote sensing is also used for early warning of droughts and food security crises42,43. Impacts of heatwaves and drought can further cascade through social systems, e.g., when the 2010 drought in Russia harmed wheat production, exports were restricted, contributing to an escalating global wheat price, which is implicated in the ‘Arab Spring’83. However, empirical research is needed to establish what is a social tipping point to avoid misuse of the concept84,85.

Resilience monitoring and tipping point early warning

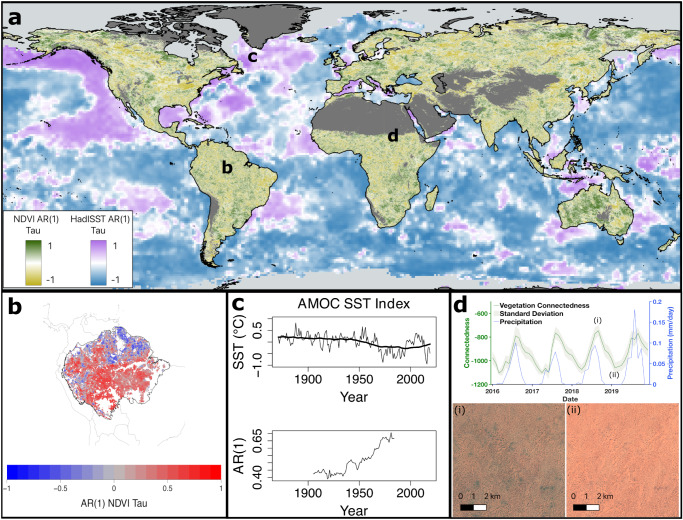

Relatively long remote sensing records, and new techniques to harmonise continuous observations over time for Essential Climate and Biodiversity Variables86,87, offer new opportunities for monitoring resilience (Box 2) and providing early warning signals (EWS) of some tipping points (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Sensing the changing resilience of tipping systems directly from observations.

Examples over different time intervals using directly and remotely sensed data: a Trends in lag-1 temporal autocorrelation (AR(1)) of global vegetation30 from monthly MODIS NDVI for 2001-2020, and of global sea surface temperatures (following the approach of ref. 166) from monthly HadISST for 1982-2021 (which includes AVHRR data). AR(1) trends are measured with Kendall’s τ rank correlation coefficient, with darker green (vegetation) and darker purple (SST) indicative of greater loss of resilience. Light grey areas correspond to pixels with sea ice and dark grey areas to those with low NDVI ( < 0.18) values. b Trends in AR(1) in the Amazon rainforest (Kendall τ) from AVHRR NDVI for 2003-2016 (redrawn from ref. 29). c Changes in SST in the Sub-Polar Gyre region from HadISST for 1870-2019 (upper panel) and associated upward trend in AR(1) (lower panel) suggesting loss of resilience of the AMOC (redrawn from ref. 37). d Fluctuations in patterned vegetation connectedness and rainfall at a site in the Sahel68 (11°37’12”N, 27°51’36”E) from Sentinel-2 and ERA5 precipitation data for 2016–2019 (upper panel), between seasonal extremes of (i) maximum and (ii) minimum connectedness (lower panels). Connectedness is quantified from feature vectors with an ‘Offset50’ metric defined in ref. 68. By measuring the decay rate of connectedness between maxima and minima, averaged over years, and compared across sites, the resilience of these dryland systems is found to decline with rainfall68.

Critical slowing down

Established early warning methods hinge on the phenomenon of critical slowing down (CSD): relatively slow forcing towards a tipping point where a system’s state loses stability, causing overall negative feedback to get weaker, slowing system dynamics including the recovery rate from small perturbations—i.e., loss of resilience. Non-tipping systems may also lose resilience31, hence additional, independent evidence of strongly amplifying feedback and/or empirical or paleoclimate evidence of past tipping, should be used to identify tipping systems. For candidate biosphere tipping systems such as tropical rainforests, boreal forests, and possibly drylands53, remote sensing provides unique opportunities to monitor resilience changes that have only begun to be exploited. Vegetation Optical Depth (VOD) data recently enabled the first global-scale empirical confirmation of CSD theory, by comparing recovery rates from perturbations with estimates based on the CSD indicators variance and lag-1 autocorrelation54.

Temporal resilience indicators

Where repeated perturbations are known to occur, changes in recovery rate can be directly monitored54,88,89. However, in most cases, resilience can only be inferred from changes in temporal autocorrelation (e.g., at lag-1; AR(1)) and variance90. These temporal EWS all require a separation of timescales: a system should be forced slower than its intrinsic response timescale for it to remain close to equilibrium. Furthermore, to detect CSD, a system must be monitored over the forcing timescale, and at a higher frequency than its response timescale. The intrinsic recovery timescales of different tipping systems range from the order of days (atmospheric circulation) or months (vegetation) to millennia (ice sheets). Climate forcing is occurring on multi-decadal to centennial timescales hence some intrinsically ‘slow’ tipping systems may not show CSD in practice. The longest ~50-year remote sensing records (i.e., Landsat) manage to capture the forcing timescale, but only the responses of relatively ‘fast’ tipping systems are monitorable with temporal EWS (those in Table 1 with a timescale of change ~10 years).

Resilience sensing of vegetation

Ecosystems are highly complex and only a subset are tipping systems, but they risk abrupt losses of functionality, with the potential to find CSD in remotely sensed data. The reliability of temporal resilience indicators, given measurement noise and data gaps, has been carefully assessed for NDVI and similar optical indices across major biomes91 and at the global scale92. The predicted relationships between recovery rate and autocorrelation or variance resilience indicators have also recently been confirmed for vegetated ecosystems at a global scale54, based on VOD and NDVI. Hence autocorrelation and variance can be used to measure vegetation resilience changes over time at high spatial resolution using remotely sensed data (Fig. 3a, b). Globally, during the last two decades, the fraction of land surface exhibiting resilience losses has increased54 compared to the 1990s. Focusing on tipping systems: The Amazon rainforest shows a large-scale loss of resilience29 over the past 20 years in VOD and NDVI (Fig. 3b), which peaked during two severe Amazon drought events in 2005 and 2010 and is greatest in drier parts of the forest and places closer to human activities (whereas during the 1990s resilience was being gained29,54). For boreal forests, NDVI fluctuations have a poor fit to an autoregressive model across large areas93, whilst VOD fluctuations54 suggest slow recovery rates (low resilience), with a heterogeneous pattern of resilience losses and gains across space. Smaller scale, societal impact tipping systems (Table 1) include forest regions subject to dieback, and analysis of Californian forests has shown CSD in NDVI prior to forest dieback events94. Opportunities for future progress depend crucially on improvements in remote sensing datasets highlighted in Box 2.

Application to other tipping systems

Although some ocean and cryosphere tipping elements are expected to be too slow to show temporal EWS in current Earth observation records, changes in the mean state, more localised tipping events, and some crucial feedbacks may be faster, more detectable, and informative of resilience changes. CSD has been detected in the analysis of ice-core-derived height variations of the central-western Greenland ice sheet36 over the last ~170 years—although contrasting patterns of mass loss acceleration in different basins indicate a complex picture95,96. As remote sensing records get longer, they can play a key role in comprehensively monitoring the dynamic state of the Greenland ice sheet. CSD has also been detected in proxies of AMOC strength37 from Atlantic SST (Fig. 3c) and SSS fluctuations observed over the last ~150 years and reconstructed over the last millennium97. Remote sensing can offer additional process-based monitoring of tipping processes in the Atlantic circulation. For instance, a large change in the sub-polar gyre (SPG) should be preceded98 by large and characteristic changes in SST and SSS, followed by changes in SSH as regional circulation changes. The same may be true for deep convection in the Nordic Seas, a key part of the AMOC. Other relatively fast tipping systems with the potential for remotely sensed temporal EWS include coral reefs99, monsoons, and atmospheric blocking events100 (Table 1). Although highly uncertain, the risks from very fast tipping in atmospheric circulation systems, including monsoons, demand continuous monitoring that remote sensing can provide59. Moreover, consistent increases in lag-1 autocorrelation of soil moisture have recently been found prior to drought-related changes in food security43, demonstrating EWS as an important potential driver of societal impact tipping.

Noise-induced tipping

Where the resilience of a tipping system is low and short-term variability in forcing (‘noise’) is sufficiently high, noise-induced tipping may occur without forewarning101. This includes cases of fast forcing of slower tipping systems (where CSD is not expected or detectable) and of increasing climate variability and extremes triggering tipping102. Remote sensing can help assess the statistical likelihood of noise-induced tipping103 through monitoring both system resilience and forcing variability (see ‘Deriving tipping probabilities’, below).

Box 2 Improving remote sensing of resilience.

Recent studies29,30,54,91–94 analysing vegetation resilience using remotely sensed data have highlighted some limitations and opportunities for improvement that are also relevant beyond the biosphere:

Data discontinuities. Even geostationary satellites do not continuously measure surface parameters. Temporal aggregation (e.g., MODIS vegetation data is provided as 8-day composites) can create pseudo-continuous records from discontinuous data, but cannot reliably fill long gaps e.g., due to cloud cover. Discontinuities in data records can have strong impacts on inferred system resilience and changes therein by biasing the variance and autocorrelation of a data set91. Novel resilience estimates that account for these discontinuities—or that do not require continuous data in the first place—are needed to take full advantage of remote sensing data.

Uncertain data. Satellite missions have been flown with vastly different design parameters and are often repurposed for novel applications. For example, AVHRR data has been used in several long-term studies of vegetation resilience29,54,93, despite being originally designed for atmospheric monitoring. The value of its relatively long sensing period (1979-) is limited by calibration problems, orbital drift, and wide sensing bands; while long-term trends in the mean provide valuable insight, changes in higher-order statistics throughout the lifespan of a sensor can propagate into resilience metrics141, and hence add uncertainty to any resilience analysis. Modern sensors provide better data, with the constraint of a relatively short instrument record; cross-referencing lower-quality data records with their modern improvements helps bridge this temporal gap (e.g., ESA’s Climate Change Initiative146).

Merging sensors. Composite data records combine multiple satellite missions into a single continuous record; VODCA is composed of passive microwave data from seven satellites with similar spectral properties38. While providing a single long-term record, this also introduces potential biases when used29,54 to estimate resilience. Changes in sensor fidelity and merging overlapping measurements both alter data quality through time; all else being equal, this will drive anti-correlation in AR(1) and variance141. This behaviour is opposite to the positively correlated increases in both metrics experienced by a system moving towards a tipping point, providing a means to distinguish their signals141. Nevertheless, single-sensor instrument records should be preferred for the estimation of resilience, and special attention must be paid to the construction of multi-instrument records so that they do not bias the inferred resilience of a system.

Interpretation. How to interpret remotely sensed resilience estimates remains a fundamental issue30. Most studies focus on NDVI which relates a spectral ratio to vegetation properties, most notably chlorophyll content and photosynthetic activity30,147. However, optical data only sample the canopy surface—particularly when vegetation is dense. Hence NDVI resilience is not whole-plant resilience30. VOD is influenced by plant water content and structure, which in turn can be correlated with biomass29, suggesting VOD resilience is closer to whole-plant resilience30. However, passive microwave (e.g., VOD) can also be influenced by surface water148, suggesting active microwave149 (radar) is slightly more robust for monitoring biomass resilience. In general, translating spectral properties into in situ ecosystem changes involves many simplifying assumptions, adding uncertainty to resilience assessments. A systemic effort to deduce which remotely sensed properties best reflect vegetation resilience is overdue.

Leveraging spatial data

The spatial coverage and fine resolution of remotely sensed data offer additional underutilized opportunities for resilience sensing and potential tipping point early warning, especially where the temporal duration of data is limited.

Space-for-time substitution

Space-for-time substitution assumes that changes in properties along spatial environmental gradients are equivalent to the response of a system to temporal changes in the same environmental driver(s). For example, where temporal remotely sensed data is sufficient to estimate resilience indicators (e.g., AR(1)) at each location, but not to detect changes in them, looking across gradients in environmental drivers can reveal how resilience varies, e.g., how resilience of tropical forests is generally lower in regions with less mean annual precipitation28. It is important to account (where possible) for other factors that also vary spatially and may influence resilience, e.g., using a linear additive model28, recognising that data for some of these factors may not be remotely sensed, e.g., soil fertility28. Also, additional information should be used to determine whether declining resilience may indicate an approach to a tipping point.

Deriving tipping probabilities

Using space-for-time substitution, remotely sensed data can be used to derive probability density functions for vegetation states, for different climate boundary conditions, e.g., mean annual precipitation. Characterising how weather variability drives vegetation variability, the resilience and size of the basin of attraction (of a current stable state) can be inferred, and from that, probabilities of leaving that state (through noise-induced tipping). Applying this approach to remotely sensed annual tree cover fraction reveals that the most resilient parts of the Amazon rainforest are those that have experienced stronger interannual rainfall variability in their long-term past40. In cases where available time series show frequent transitions between alternative attractors, tipping probabilities can be estimated directly103,104, e.g., using paleoclimate data and lake data103. Hence, remote sensing data for systems that have undergone multiple abrupt shifts, such as lakes105, could be used to estimate tipping probabilities.

Spatial early warning indicators

EWS in spatially extended systems depends on the nature of spatial interactions, which remote sensing can help resolve. For macro tipping, responses are expected to be spatially homogeneous, whereas, for other tipping phenomena involving heterogeneous feedbacks and spatial interactions, these can determine the scale of tipping106 and where EWS are expected107. For example, reduced rainfall could lead to vegetation change at different times in different places, but the locations may be causally linked via moisture recycling feedbacks107–109. Spatial EWS can be expected as increases in spatial variance or skewness4,110,111 and cross-correlations41. The detection of spatial EWS requires that a tipping system is monitored at least at the spatial resolution over which its reinforcing feedbacks manifest spatially112. Fine-resolution remote sensing can enable this, as demonstrated across rainfall gradients in the tropics where spatial EWS have been found before the switch of savanna/forest vegetation types113,114.

Spatially patterned systems

In systems with regular spatial structure, such as the patterned vegetation found in drylands68 (Fig. 3d), spatial self-organisation (creating multiple stable patterns states at low rainfall) may enable ecosystems to evade a tipping point and associated abrupt loss of ecosystem services67. Plant-soil feedback can be key to spatial self-organisation and affect community assembly and resilience above and below ground66. Fine spatial resolution remote sensing data that are continuous in time across large areas has enabled quantification of pattern connectedness and monitoring of its temporal variation as an aboveground resilience indicator68 (Fig. 3d). However, to fully unravel ecosystem complexity also requires complementary approaches, including on-site field studies.

Combining data and models

Combining remotely sensed data and Earth system models offers opportunities to improve forecasting of tipping points, which is crucial given persistent parametric and structural errors in the ability of models to predict tipping points32.

Designing remote sensing strategies

Earth system models can guide where spatially to look for temporal EWS, for example in ocean circulation39 or ice sheets61. Model simulations could also help identify which processes and where best to remotely monitor for spatial EWS of a tipping point. For example, examining simulated SSH, SST, and SSS data prior to modelled abrupt shifts in the sub-polar gyre57,98, incorporating known uncertainties in remote sensing, could determine which remotely sensed data are most informative for EWS and where additional monitoring could add value.

Emergent constraints

Emergent constraints47 describe a semi-empirical method whereby models identify observable targets that can constrain future predictions115. Emergent constraints allow observational (including remotely sensed) data to constrain the distribution of long-term projections from a large multi-model ensemble. Most focus has been on linear responses, e.g., precipitation forecasts116, but emergent constraints can be developed and applied to tipping responses, as has been done for SPG instability57,98 and Amazon dieback117. Theoretical progress is needed to build confidence in this relatively sensitive and empirical approach.

Decadal predictions

Decadal climate predictions already highlight the benefit of initialising climate models from observed states118, assimilating the best available observations, including from remote sensing for spatial-temporal coverage119. This approach greatly improves the predictability of the North Atlantic Oscillation120. There is a clear opportunity to apply it to tipping elements with a decadal memory component. For instance, the SPG shows abrupt changes in several CMIP5 and CMIP6 model simulations57,98, but it is unclear how close this tipping point is or how it is mechanistically related to the AMOC. Initialising those models with remotely sensed data could provide an improved assessment of tipping event timing, tipping system interactions, and, through large ensembles, a statistical assessment of likelihood. Decadal prediction systems are now going beyond climate models to full Earth system models121,122, opening further opportunities for the assimilation of remotely sensed data to improve forecasting of ‘fast’ biogeochemical tipping systems e.g., Sahel vegetation.

Assessing tipping interactions

Remote sensing can provide critical information to improve the assessment of interactions between tipping systems, including the potential for cascades10, by regularly and consistently observing multiple modelled variables across space and time.

Current understanding

Current assessments of tipping interactions come from paleoclimate proxy data8, expert elicitation for a subset of tipping elements123, model studies of specific tipping element interactions124, or qualitative assessment across different scales of tipping system3. Idealised models have been used to assess the transient48 or eventual equilibrium9 response to the combined effects of interactions amongst a subset of tipping elements—suggesting they increase risk overall9,48, lowering tipping point thresholds48—but this is based on a dated expert elicitation123. Large uncertainties remain over whether particular interactions are net stabilising or destabilising123.

Detecting interactions

Remotely sensed data (Table 1) can provide crucial information to detect or validate tipping system interactions predicted by Earth system models and constrain their signs and strengths. Taking a previously identified example of a key interaction chain46, backed up by detailed model studies125: Rapid melting of the GrIS is already well-observed by altimetry and gravimetry and is predicted to increase the likelihood of crossing tipping points in the sub-polar gyre (SPG) circulation and the AMOC124—albeit dependent on model and resolution126–128. Associated changes in North Atlantic SSS, SST, and the SPG circulation should be observable through passive microwave, thermal infrared, and altimetry, respectively. Effects on AMOC strength should also become detectable in SST and SSS spatial fingerprints. Models, paleo-data129,130 and the observational record show that AMOC weakening shifts the intertropical convergence zone (ITCZ) southwards, affecting tropical monsoon systems, but whether this has a destabilising9,123 or stabilising131,132 effect on the Amazon rainforest is currently unclear. Remotely sensed data can help resolve this through detecting movements in the position of the ITCZ, variations in tropical Atlantic SSTs, and resulting changes in precipitation, water level, and storage over the Amazon region in outgoing longwave radiation, radar, radar altimetry, and gravimetry. Destabilisation of the Amazon rainforest is already identifiable in VOD and NDVI29. Amazon deforestation and/or climate change-induced dieback might trigger monsoon shifts because the South American monsoon depends critically on evapotranspiration from the rainforest108, which can be probed with a combination of remote sensing and models.

Inferring causality

Applying methods of data-driven causality detection133 to time series134 and across spatial135 remotely sensed data can help establish causal relationships between tipping systems and eliminate confounding factors in apparently coupled changes. Remotely sensed data provide a promising basis to recover the network of interactions between faster tipping systems, building on the successful recovery of causal connections between geophysical variables136, including ice cover in the Barents Sea tipping element2 and mid-latitude circulation134 and Walker circulation couplings in the equatorial Pacific137. Remotely sensed data could also be used to infer causal effects of climate on this network, building on success for vegetation138,139. For fast tipping systems that have undergone abrupt shifts, convergent cross-mapping140 could be attempted to establish whether a deterministic nonlinear attractor can be recovered from remotely sensed data.

Outlook

We have highlighted the unique value that satellite remote sensing, with its global coverage, fine resolution, and increasing diversity of variables, can bring to advancing the understanding, detection and anticipation of climate change tipping points, and their interactions, across scales. Given the risk that tipping points pose this should be urgently informing both future missions and the extraction of information from existing remotely sensed data. Here we recommend key areas for advancing research to remotely sense climate change tipping points across scales.

Sensing system

Establishing a tipping point sensing system would provide a unifying research framework to bring together the Earth system and Earth observation communities. It would combine data and models to identify and anticipate potential tipping points, demanding advances in data, methods, and analysis. This should start with a systematic scan of existing remotely sensed data to detect abrupt shifts and regions of multi-stability with the potential for future tipping, and a systematic analysis of the potential for temporal and spatial EWS in faster tipping systems, given current data or prospective missions. Models should guide what and where to monitor tipping processes and temporal and spatial EWS in remotely sensed data. Conversely, remote sensing data should be used to constrain model projections of the location and timing of tipping points under specific forcing scenarios. The resulting tighter integration of observations, models, and theory would address the urgent need for improved scientific information on tipping point risks to inform policy.

Improving data

The veracity of a tipping point sensing system depends crucially on improving the salience, accuracy, continuity, and consistency of remotely sensed data. We recommend revising acquisition strategies and exploiting special constellations (e.g., synchronised orbits, bistatic or multi-static radar) toward smarter use of existing remotely sensed data. To make ecosystem monitoring more salient, calls for improved vegetation indices that link to key properties such as biomass (e.g., utilising active microwave). Enhancing data accuracy calls for ongoing utilisation of cloud-insensitive wavelengths (e.g., SAR) with improved consistency of coverage. Temporal resilience sensing would benefit from enhanced access to single-sensor data, and improved multi-instrument records that minimise introducing artefacts141 (see Box 2). Spatial resilience sensing would benefit from open access to very high-resolution spatial data and computational power to analyse it.

Refining methods

The veracity of a tipping point sensing system also depends on refining methods of analysing remotely sensed data. Recent advances in training deep learning to detect and provide early warning of tipping points142,143 should be applied to remotely sensed data, including using segmentation algorithms to complement edge detection in spatial data144. Methods of estimating resilience based on spatial statistics should be applied to the high spatial but low temporal resolution of some existing (e.g., Landsat) and new (e.g., GEDI) data, and duly refined. New data (e.g., GEDI, Sentinel-6, EnMAP) demand resilience sensing methods that limit the impacts of data discontinuities, of merging signals from different sensors, and of low temporal resolution. The comparison of recovery rates measured after perturbation and inferred from AR(1) and variance should be extended beyond vegetation indexes54 to underpin the wider application of temporal EWS. Multivariate Earth observations should be used to help resolve different mechanistic explanations for observed increases in autocorrelation and variance, e.g., combining vegetation indexes (such as NDVI and VOD), rainfall statistics, and deforestation data to understand signals of changing Amazon rainforest resilience29.

Conclusion

The resulting fine-resolution spatial-temporal sensing of tipping systems can support policy-making and risk management at regional, national, and international scales. It can actively help to protect numerous human lives and livelihoods that are at risk from climate change tipping points. Return on investment is also expected to be good, as the framework for Earth observation technology is largely in place and expanding rapidly with commercial partnerships with public agencies. Key opportunities lie in smarter use and combination of existing remote sensing data to detect and forewarn of tipping points across scales.

Acknowledgements

This paper is an outcome of the ‘Tipping Points in the Earth’s Climate’ Forum held at the International Space Science Institute (ISSI), Bern, Switzerland (26-29 January 2021). T.M.L., C.A.B., and J.E.B. were supported by the Leverhulme Trust (RPG-2018-046). T.M.L., J.F.A., C.A.B., and J.E.B. were also supported by DARPA. A.B. was supported by the European Space Agency through Permafrost_cci (4000123681/18/INB) and AMPAC-Net (4000137912/22/I-DT), and the European Research Council project No. 951288 (Q-Arctic). S.B. and N.B. acknowledge funding from the Volkswagen Stiftung, the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement number 820970 (TiPES contribution #273) and under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement number 956170, as well as from the Federal Ministry of Education and Research under grant number 01LS2001A. A.M.C was supported by the Oppenheimer Programme in African Landscape Systems co-funded by Oppenheimer Generations Research and Conservation. T.S. acknowledges support from the DFG STRIVE project (SM 710/2-1). D.S. received financial support from the French government in the framework of the University of Bordeaux’s IdEx “Investments for the Future” programme/RRI Tackling Global Change and from the UKRI DECADAL project.

Author contributions

T.M.L. led the writing with J.F.A., A.B., S.B., C.A.B., J.E.B., A.C., A.M.C., S.H., T.L., B.P., A.S., T.S., D.S., R.W., and N.B. all inputting. A.B. and A.S. helped refine the table. J.F.A., C.A.B. and J.E.B. produced the figures.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Data availability

All data used in Fig. 3 are freely available from the following sources: MODIS data from NASA: https://modis.gsfc.nasa.gov/data/. HadISST data from the Met Office: https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/hadobs/. AVHRR NDVI data from USGS: https://www.usgs.gov/centers/eros/science/usgs-eros-archive-avhrr-normalized-difference-vegetation-index-ndvi-composites. Sentinel-2 data from Copernicus: https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/explore-data/data-collections/sentinel-data/sentinel-2. ERA5 precipitation data from Copernicus: 10.24381/cds.adbb2d47. The AMOC SST Index can be found as ‘SST_SG_GM’ in ref. 37.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

3/1/2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41467-024-45881-0

References

- 1.Lenton TM, et al. Tipping elements in the Earth’s climate system. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:1786–1793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705414105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armstrong McKay DI, et al. Exceeding 1.5 C global warming could trigger multiple climate tipping points. Science. 2022;377:eabn7950. doi: 10.1126/science.abn7950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rocha JC, Peterson G, Bodin Ö, Levin S. Cascading regime shifts within and across scales. Science. 2018;362:1379–1383. doi: 10.1126/science.aat7850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scheffer M, et al. Early warning signals for critical transitions. Nature. 2009;461:53–59. doi: 10.1038/nature08227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gasser T, et al. Path-dependent reductions in CO2 emission budgets caused by permafrost carbon release. Nat. Geosci. 2018;11:830–835. doi: 10.1038/s41561-018-0227-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wunderling N, Willeit M, Donges JF, Winkelmann R. Global warming due to loss of large ice masses and Arctic summer sea ice. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:5177. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18934-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu W, Fedorov AV, Xie S-P, Hu S. Climate impacts of a weakened Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation in a warming climate. Sci. Adv. 2020;6:eaaz4876. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaz4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brovkin V, et al. Past abrupt changes, tipping points and cascading impacts in the Earth system. Nat. Geosci. 2021;14:550–558. doi: 10.1038/s41561-021-00790-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wunderling N, Donges JF, Kurths J, Winkelmann R. Interacting tipping elements increase risk of climate domino effects under global warming. Earth Syst. Dynam. 2021;12:601–619. doi: 10.5194/esd-12-601-2021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klose AK, Karle V, Winkelmann R, Donges JF. Emergence of cascading dynamics in interacting tipping elements of ecology and climate. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2020;7:200599. doi: 10.1098/rsos.200599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Comiso, J. C., Parkinson, C. L., Gersten, R. & Stock, L. Accelerated decline in the Arctic sea ice cover. Geophys. Res. Lett.35, L01703 (2008).

- 12.Cook AJ, Vaughan DG. Overview of areal changes of the ice shelves on the Antarctic Peninsula over the past 50 years. Cryosphere. 2010;4:77–98. doi: 10.5194/tc-4-77-2010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Velicogna I, Wahr J. Measurements of time-variable gravity show mass loss in Antarctica. Science. 2006;311:1754–1756. doi: 10.1126/science.1123785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rignot E, Kanagaratnam P. Changes in the velocity structure of the Greenland ice sheet. Science. 2006;311:986–990. doi: 10.1126/science.1121381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas R, et al. Accelerated sea-level rise from West Antarctica. Science. 2004;306:255–258. doi: 10.1126/science.1099650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rignot E, Mouginot J, Morlighem M, Seroussi H, Scheuchl B. Widespread, rapid grounding line retreat of Pine Island, Thwaites, Smith, and Kohler glaciers, West Antarctica, from 1992 to 2011. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2014;41:3502–3509. doi: 10.1002/2014GL060140. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joughin I, Smith BE, Medley B. Marine ice sheet collapse potentially under way for the Thwaites Glacier Basin, West Antarctica. Science. 2014;344:735–738. doi: 10.1126/science.1249055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rignot E, et al. Four decades of Antarctic ice sheet mass balance from 1979–2017. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2019;116:1095–1103. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1812883116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shepherd A, et al. Trends in Antarctic ice sheet elevation and mass. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2019;46:8174–8183. doi: 10.1029/2019GL082182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Konrad H, et al. Net retreat of Antarctic glacier grounding lines. Nat. Geosci. 2018;11:258–262. doi: 10.1038/s41561-018-0082-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mouginot J, Rignot E, Scheuchl B. Sustained increase in ice discharge from the Amundsen Sea Embayment, West Antarctica, from 1973 to 2013. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2014;41:1576–1584. doi: 10.1002/2013GL059069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bjordal J, Storelvmo T, Alterskjær K, Carlsen T. Equilibrium climate sensitivity above 5 °C plausible due to state-dependent cloud feedback. Nat. Geosci. 2020;13:718–721. doi: 10.1038/s41561-020-00649-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scheffer M, Hirota M, Holmgren M, Van Nes EH, Chapin FS. Thresholds for boreal biome transitions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:21384–21389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219844110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abis B, Brovkin V. Environmental conditions for alternative tree-cover states in high latitudes. Biogeosciences. 2017;14:511–527. doi: 10.5194/bg-14-511-2017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirota M, Holmgren M, Van Nes EH, Scheffer M. Global resilience of tropical forest and savanna to critical transitions. Science. 2011;334:232–235. doi: 10.1126/science.1210657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Staver AC, Archibald S, Levin SA. The global extent and determinants of Savanna and forest as alternative biome states. Science. 2011;334:230–232. doi: 10.1126/science.1210465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wuyts B, Champneys AR, House JI. Amazonian forest-savanna bistability and human impact. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:15519. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Verbesselt J, et al. Remotely sensed resilience of tropical forests. Nat. Clim. Change. 2016;6:1028–1031. doi: 10.1038/nclimate3108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boulton CA, Lenton TM, Boers N. Pronounced loss of Amazon rainforest resilience since the early 2000s. Nat. Clim. Change. 2022;12:271–278. doi: 10.1038/s41558-022-01287-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lenton TM, et al. A resilience sensing system for the biosphere. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2022;377:20210383. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2021.0383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kéfi S, Dakos V, Scheffer M, Van Nes EH, Rietkerk M. Early warning signals also precede non-catastrophic transitions. Oikos. 2012;122:641–648. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0706.2012.20838.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boers N, Ghil M, Stocker TF. Theoretical and paleoclimatic evidence for abrupt transitions in the Earth system. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022;17:093006. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/ac8944. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Robinson A, Calov R, Ganopolski A. Multistability and critical thresholds of the Greenland ice sheet. Nat. Clim. Change. 2012;2:429–432. doi: 10.1038/nclimate1449. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu, W., Xie, S.-P., Liu, Z. & Zhu, J. Overlooked possibility of a collapsed Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation in warming climate. Sci. Adv.3, e1601666 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Jackson LC, Wood RA. Hysteresis and Resilience of the AMOC in an Eddy-Permitting GCM. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2018;45:8547–8556. doi: 10.1029/2018GL078104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boers N, Rypdal M. Critical slowing down suggests that the western Greenland ice sheet is close to a tipping point. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2021;118:e2024192118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2024192118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boers N. Observation-based early-warning signals for a collapse of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation. Nat. Clim. Change. 2021;11:680–688. doi: 10.1038/s41558-021-01097-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moesinger L, et al. The global long-term microwave Vegetation Optical Depth Climate Archive (VODCA) Earth Syst. Sci. Data. 2020;12:177–196. doi: 10.5194/essd-12-177-2020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boulton CA, Allison LC, Lenton TM. Early warning signals of Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation collapse in a fully coupled climate model. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:5752. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ciemer C, et al. Higher resilience to climatic disturbances in tropical vegetation exposed to more variable rainfall. Nat. Geosci. 2019;12:174–179. doi: 10.1038/s41561-019-0312-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dakos V, van Nes E, Donangelo R, Fort H, Scheffer M. Spatial correlation as leading indicator of catastrophic shifts. Theor. Ecol. 2010;3:163–174. doi: 10.1007/s12080-009-0060-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krishnamurthy R PK, Fisher JB, Schimel DS, Kareiva PM. Applying tipping point theory to remote sensing science to improve early warning drought signals for food security. Earth’s Future. 2020;8:e2019EF001456. doi: 10.1029/2019EF001456. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krishnamurthy R PK, Fisher JB, Choularton RJ, Kareiva PM. Anticipating drought-related food security changes. Nat. Sustain. 2022;5:956–964. doi: 10.1038/s41893-022-00962-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thellmann K, et al. Tipping points in the supply of ecosystem services of a mountainous watershed in Southeast Asia. Sustainability. 2018;10:2418. doi: 10.3390/su10072418. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mercer JH. West Antarctic ice sheet and CO2 greenhouse effect: a threat of disaster. Nature. 1978;271:321–325. doi: 10.1038/271321a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lenton TM, et al. Climate tipping points—too risky to bet against. Nature. 2019;575:592–595. doi: 10.1038/d41586-019-03595-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hall A, Cox P, Huntingford C, Klein S. Progressing emergent constraints on future climate change. Nat. Clim. Change. 2019;9:269–278. doi: 10.1038/s41558-019-0436-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cai Y, Lenton TM, Lontzek TS. Risk of multiple interacting tipping points should encourage rapid CO2 emission reduction. Nat. Clim. Change. 2016;6:520–525. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2964. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Committee on Climate Change. Net Zero—The UK’s Contribution to Stopping Global Warming. (Committee on Climate Change, 2019).

- 50.Lenton TM, Ciscar J-C. Integrating tipping points into climate impact assessments. Clim. Change. 2013;117:585–597. doi: 10.1007/s10584-012-0572-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Collins, M. et al. in The Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate: Special Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds H.-O. Pörtner et al.) 589–656 (Cambridge University Press, 2019).

- 52.Sellers PJ, Schimel DS, Moore B, Liu J, Eldering A. Observing carbon cycle-climate feedbacks from space. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:7860–7868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1716613115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Berdugo M, Gaitán JJ, Delgado-Baquerizo M, Crowther TW, Dakos V. Prevalence and drivers of abrupt vegetation shifts in global drylands. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2022;119:e2123393119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2123393119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smith T, Traxl D, Boers N. Empirical evidence for recent global shifts in vegetation resilience. Nat. Clim. Change. 2022;12:477–484. doi: 10.1038/s41558-022-01352-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Scheffer M, Carpenter S, Foley JA, Folke C, Walker B. Catastrophic shifts in ecosystems. Nature. 2001;413:591–596. doi: 10.1038/35098000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Biggs, R., Peterson, G. D. & Rocha, J. C. The Regime Shifts Database: a framework for analyzing regime shifts in social-ecological systems. Ecol. Soc.23, 9 (2018).

- 57.Swingedouw D, et al. On the risk of abrupt changes in the North Atlantic subpolar gyre in CMIP6 models. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2021;1504:187–201. doi: 10.1111/nyas.14659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Swingedouw D, et al. Early warning from space for a few key tipping points in physical, biological, and social-ecological systems. Surv. Geophys. 2020;41:1237–1284. doi: 10.1007/s10712-020-09604-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kumar P, Kishtawal CM, Pal PK. Impact of satellite rainfall assimilation on Weather Research and Forecasting model predictions over the Indian region. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 2014;119:2017–2031. doi: 10.1002/2013JD020005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pattyn F, Morlighem M. The uncertain future of the Antarctic ice sheet. Science. 2020;367:1331–1335. doi: 10.1126/science.aaz5487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rosier SHR, et al. The tipping points and early warning indicators for Pine Island Glacier, West Antarctica. Cryosphere. 2021;15:1501–1516. doi: 10.5194/tc-15-1501-2021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Feldmann J, Levermann A. Collapse of the West Antarctic ice sheet after local destabilization of the Amundsen Basin. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 2015;112:14191–14196. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1512482112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Staal A, et al. Forest-rainfall cascades buffer against drought across the Amazon. Nat. Clim. Change. 2018;8:539–543. doi: 10.1038/s41558-018-0177-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hansen MC, et al. High-Resolution Global Maps of 21st-Century Forest Cover Change. Science. 2013;342:850–853. doi: 10.1126/science.1244693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hansen MC, et al. The fate of tropical forest fragments. Sci. Adv. 2020;6:eaax8574. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aax8574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Inderjit, Callaway RM, Meron E. Belowground feedbacks as drivers of spatial self-organization and community assembly. Phys. Life Rev. 2021;38:1–24. doi: 10.1016/j.plrev.2021.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rietkerk M, et al. Evasion of tipping in complex systems through spatial pattern formation. Science. 2021;374:eabj0359. doi: 10.1126/science.abj0359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Buxton JE, et al. Quantitatively monitoring the resilience of patterned vegetation in the Sahel. Glob. Change Biol. 2021;28:571–587. doi: 10.1111/gcb.15939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Druckenbrod DL, et al. Redefining temperate forest responses to climate and disturbance in the eastern United States: New insights at the mesoscale. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2019;28:557–575. doi: 10.1111/geb.12876. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Boulton C, Lenton T. A new method for detecting abrupt shifts in time series. F1000Research. 2019;8:746. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.19310.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bernardino PN, et al. Global-scale characterization of turning points in arid and semi-arid ecosystem functioning. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2020;29:1230–1245. doi: 10.1111/geb.13099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nitze I, Grosse G, Jones BM, Romanovsky VE, Boike J. Remote sensing quantifies widespread abundance of permafrost region disturbances across the Arctic and Subarctic. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:5423. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07663-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kumar SS, et al. Alternative vegetation states in tropical forests and Savannas: the search for consistent signals in diverse remote sensing data. Remote Sens. 2019;11:815. doi: 10.3390/rs11070815. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zeng Y, et al. Towards a traceable climate service: assessment of quality and usability of essential climate variables. Remote Sens. 2019;11:1186. doi: 10.3390/rs11101186. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Duveiller G, et al. Revealing the widespread potential of forests to increase low level cloud cover. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:4337. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24551-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Deng Z, et al. Comparing national greenhouse gas budgets reported in UNFCCC inventories against atmospheric inversions. Earth Syst. Sci. Data. 2022;14:1639–1675. doi: 10.5194/essd-14-1639-2022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sorg A, Bolch T, Stoffel M, Solomina O, Beniston M. Climate change impacts on glaciers and runoff in Tien Shan (Central Asia) Nat. Clim. Change. 2012;2:725–731. doi: 10.1038/nclimate1592. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Watson SCL, et al. Does agricultural intensification cause tipping points in ecosystem services? Landsc. Ecol. 2021;36:3473–3491. doi: 10.1007/s10980-021-01321-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Miralles DG, Teuling AJ, van Heerwaarden CC, Vilà-Guerau de Arellano J. Mega-heatwave temperatures due to combined soil desiccation and atmospheric heat accumulation. Nat. Geosci. 2014;7:345–349. doi: 10.1038/ngeo2141. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Reichstein M, et al. Reduction of ecosystem productivity and respiration during the European summer 2003 climate anomaly: a joint flux tower, remote sensing and modelling analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 2007;13:634–651. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2006.01224.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Witte JC, et al. NASA A-Train and Terra observations of the 2010 Russian wildfires. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2011;11:9287–9301. doi: 10.5194/acp-11-9287-2011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shaposhnikov D, et al. Mortality related to air pollution with the Moscow heat wave and wildfire of 2010. Epidemiology. 2014;25:359–364. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hunt E, et al. Agricultural and food security impacts from the 2010 Russia flash drought. Weather Clim. Extremes. 2021;34:100383. doi: 10.1016/j.wace.2021.100383. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kopp RE, Shwom RL, Wagner G, Yuan J. Tipping elements and climate–economic shocks: Pathways toward integrated assessment. Earth’s Future. 2016;4:346–372. doi: 10.1002/2016EF000362. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Milkoreit M. Social tipping points everywhere?—Patterns and risks of overuse. WIREs Clim. Change. 2022;14:e813. doi: 10.1002/wcc.813. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mortimer C, et al. Benchmarking algorithm changes to the Snow CCI+ snow water equivalent product. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022;274:112988. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2022.112988. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Paul S, Hendricks S, Ricker R, Kern S, Rinne E. Empirical parametrization of Envisat freeboard retrieval of Arctic and Antarctic sea ice based on CryoSat-2: progress in the ESA Climate Change Initiative. Cryosphere. 2018;12:2437–2460. doi: 10.5194/tc-12-2437-2018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wissel C. A universal law of the characteristic return time near thresholds. Oecologia. 1984;65:101–107. doi: 10.1007/BF00384470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.De Keersmaecker W, et al. Evaluating recovery metrics derived from optical time series over tropical forest ecosystems. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022;274:112991. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2022.112991. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kubo R. The fluctuation-dissipation theorem. Rep. Prog. Phys. 1966;29:255–284. doi: 10.1088/0034-4885/29/1/306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.De Keersmaecker W, et al. How to measure ecosystem stability? An evaluation of the reliability of stability metrics based on remote sensing time series across the major global ecosystems. Glob. Change Biol. 2014;20:2149–2161. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Forzieri G, Dakos V, McDowell NG, Ramdane A, Cescatti A. Emerging signals of declining forest resilience under climate change. Nature. 2022;608:534–539. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04959-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.De Keersmaecker W, et al. A model quantifying global vegetation resistance and resilience to short-term climate anomalies and their relationship with vegetation cover. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2015;24:539–548. doi: 10.1111/geb.12279. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Liu Y, Kumar M, Katul GG, Porporato A. Reduced resilience as an early warning signal of forest mortality. Nat. Clim. Change. 2019;9:880–885. doi: 10.1038/s41558-019-0583-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.King MD, et al. Dynamic ice loss from the Greenland ice sheet driven by sustained glacier retreat. Commun. Earth Environ. 2020;1:1. doi: 10.1038/s43247-020-0001-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Khan SA, et al. Accelerating ice loss from peripheral glaciers in North Greenland. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2022;49:e2022GL098915. doi: 10.1029/2022GL098915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Michel SLL, et al. Early warning signal for a tipping point suggested by a millennial Atlantic Multidecadal Variability reconstruction. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:5176. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-32704-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sgubin, G., Swingedouw, D., Drijfhout, S., Mary, Y. & Bennabi, A. Abrupt cooling over the North Atlantic in modern climate models. Nat. Commun.8, 14375 (2017). Identifies a tipping point of deep convection collapse in the North Atlantic subpolar gyre occurring in several climate models at low levels of global warming.

- 99.Knudby A, Jupiter S, Roelfsema C, Lyons M, Phinn S. Mapping coral reef resilience indicators using field and remotely sensed data. Remote Sens. 2013;5:1311–1334. doi: 10.3390/rs5031311. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Tantet A, van der Burgt FR, Dijkstra HA. An early warning indicator for atmospheric blocking events using transfer operators. Chaos: Interdiscip. J. Nonlinear Sci. 2015;25:036406. doi: 10.1063/1.4908174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lenton TM. Early warning of climate tipping points. Nat. Clim. Change. 2011;1:201–209. doi: 10.1038/nclimate1143. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Turner MG, et al. Climate change, ecosystems and abrupt change: science priorities. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2020;375:20190105. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2019.0105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Arani BMS, Carpenter SR, Lahti L, Nes EHV, Scheffer M. Exit time as a measure of ecological resilience. Science. 2021;372:eaay4895. doi: 10.1126/science.aay4895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hassanibesheli F, Boers N, Kurths J. Reconstructing complex system dynamics from time series: a method comparison. N. J. Phys. 2020;22:073053. doi: 10.1088/1367-2630/ab9ce5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Gilarranz LJ, Narwani A, Odermatt D, Siber R, Dakos V. Regime shifts, trends, and variability of lake productivity at a global scale. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2022;119:e2116413119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2116413119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.van Nes EH, Scheffer M. Implications of spatial heterogeneity for catastrophic regime shifts in ecosystems. Ecology. 2005;86:1797–1807. doi: 10.1890/04-0550. [DOI] [Google Scholar]