Abstract

Quality control (QC) in mass spectrometry (MS)-based proteomics is mainly based on data-dependent acquisition (DDA) analysis of standard samples. Here, we collect 2754 files acquired by data independent acquisition (DIA) and paired 2638 DDA files from mouse liver digests using 21 mass spectrometers across nine laboratories over 31 months. Our data demonstrate that DIA-based LC-MS/MS-related consensus QC metrics exhibit higher sensitivity compared to DDA-based QC metrics in detecting changes in LC-MS status. We then prioritize 15 metrics and invite 21 experts to manually assess the quality of 2754 DIA files based on those metrics. We develop an AI model for DIA-based QC using 2110 training files. It achieves AUCs of 0.91 (LC) and 0.97 (MS) in the first validation dataset (n = 528), and 0.78 (LC) and 0.94 (MS) in an independent validation dataset (n = 116). Finally, we develop an offline software called iDIA-QC for convenient adoption of this methodology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rapid advancement of mass spectrometry (MS) fosters the evolution of high-throughput, multi-batch, and large-scale quantitative proteomics1,2,3. A high-performing and stable liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) workflow is essential for the precise identification and quantification of proteins4,5,6. Currently, the assessment of instrument performance relies primarily on the periodic analysis of a quality control (QC) sample. The stability of the instrument is evaluated based on variations of the QC data. In a typical proteomics experiment, the optimal condition results in a satisfactory outcome as reflected by the number of peptide and protein identifications. Therefore, in most cases, proteomics practitioners adopt the number of identified peptides and proteins as a simple and direct measure for quality control of LC-MS. Nonetheless, pinpointing the cause is usually challenging, time-consuming and highly empirical when the figures fall below the anticipated range. In quantitative experiments, it is not uncommon for the quantitative accuracy and reproducibility to be compromised without reducing the peptide and protein identifications. Therefore, the development of more sophisticated and elegant parameters involving the LC and MS systems has been proposed. Most QC studies focused on data-dependent acquisition (DDA) MS experiments using a specific LC-MS system. Rudnick et al.7 published the milestone paper in the field, introducing 46 metrics related to the QC of DDA data. The 46 metrics concern chromatography, ion source, MS1, dynamic sampling, MS2, and peptide identification. The Tabb team further refined these parameters and developed QuaMeter for DDA QC of multivendor LC-MS instruments8,9. Matzke10 et al. reported a multivariate statistical strategy to identify outlier LC-MS runs. The Payne team manually curated 1150 multivendor DDA-MS raw files and developed machine learning models for QC11. The Laukens team and the Martens team have developed new file format and software tools to describe and evaluate the quality of DDA-MS files12,13,14. The MacCoss team have reported Skyline-based QC software tools SProCoP15 and Panorama AutoQC webserver16 for targeted proteomics experiments, i.e. selected/multiple reaction monitoring (SRM/MRM).

Nevertheless, these QC studies and software tools are exclusively for DDA-MS and/or SRM-based targeted proteomics. Currently, there has been no systematic investigation of data-independent acquisition (DIA) QC. This lack of investigation is not surprising, considering that the generation of large DIA data sets only emerged recently thanks to the rapid progresses of LC and MS systems2,17,18,19. Nowadays, DIA-MS has become arguably the method of choice for large-scale label-free quantitative proteomics experiments, not only for body fluid20,21, bulk cell and tissue specimens22,23,24, but also for single cell proteomics25,26. The success of DIA experiments requires robust LC and MS systems, therefore QC is crucial. However, the existing QC pipelines mentioned above cannot be directly applied to analyze large-scale DIA experiments.

In this work, we establish a computational pipeline demonstrating that DIA-based quality control outperforms DDA-based approaches in detecting changes in LC-MS status across multivendor systems, validated through data from 21 mass spectrometers over 31 months and further supported by an AI model built from expert-inspected QC metrics. Nine laboratories dedicate 21 high-resolution mass spectrometers of eight models, including Orbitrap, TripleTOF, and timsTOF Pro series instruments, for this comprehensive QC study. The same mouse liver digests are injected into these mass spectrometers for both DDA and DIA analyses. The MS operators monitor the performance of these instruments for up to 31 months, and all the maintenance data are recorded. This allows an unbiased comparison of DDA and DIA for LC-MS QC. Our data show that the DIA-based QC outperforms the DDA-based QC in detecting changes in LC-MS status. Twenty-one experts are recruited from 10 laboratories for manual inspection of the 2754 DIA QC files based on 15 prioritized consensus QC metrics. These original manually inspected data are then used to build an AI model, which is further implemented as a standalone software tool for community applications.

Results

Longitudinal monitoring the performance of 21 mass spectrometers

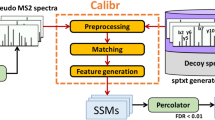

Firstly, we generated paired DDA and DIA files as QC using a homogenous mouse liver digest samples from six mice, called Westlake Mouse Liver Digests (WMLD), employing pressure cycling technology (PCT)-assisted sample preparation27,28 (Fig. 1). The WMLD aliquots, reconstituted using a standardized protocol, were distributed to nine different laboratories. Altogether, 21 mass spectrometers of eight different types were included in this study, including Orbitrap, TripleTOF, and timsTOF Pro series mass spectrometers (Fig. 1; Supplementary Fig. 1). Each instrument was operated to generate a pair of DDA and DIA runs using a 250 to 1000 ng WMLD sample over an effective LC gradient of 30 min, with the corresponding run-to-run time ranging from 40 to 55 min with different LC systems (Supplementary Data 1). The 21 LC-MS systems from nine laboratories were monitored for a period ranging from 91 to 873 days, with a median duration of 321 days (Fig. 2A). The entire project spans over 125 weeks. Detailed data acquisition parameters are provided in Supplementary Data 1.

A Generation of 2754 annotated DIA files using 21 mass spectrometers of eight types from nine platforms. B Peptide precursors pre-selection from retrospective datasets of 221 DIA files. C Establishment of a machine learning model for quality control of DIA-based proteomics. FWHM full width at half maximum, RT retention time, PIC precursor ion chromatogram.

A The landscape of 2638 DIA files and 785 LC-MS maintenance events for 21 MS instruments over 873 days of data acquisition. Each MS instrument is represented by two circles of the same color, with the acquired DIA files shown as triangles positioned at the outermost part of the circle. The circles in different colors represent different instruments. The varied sizes of rings in the innermost circle represent the number of maintenance events performed on each day. The icons, distinguished by their colors and shapes, represent different types of maintenance. D, timsTOF Pro; W, TripleTOF series; R, Orbitrap series instruments. Bar chart (B) shows the frequency of LC-MS maintenance events for each instrument. Box plot (C) illustrates the distribution of identified proteins across the 2638 DIA files for the 21 MS instruments. The boxes, displayed in various colors, represent different types of instruments. Boxes are first and third quartiles, the center line is median, whiskers are ± 1.5 interquartile range, and dots are individual data points. Source data are provided with this paper.

A total of 2638 DIA raw files and 2638 paired DDA raw files were obtained, accompanied by a detailed maintenance log (Supplementary Data 2). Throughout this period, we conducted a total of 785 LC-MS maintenance procedures, which could be categorized into three primary groups: LC maintenance, MS front-end maintenance, and MS back-end maintenance (Fig. 2). Additionally, these maintenance procedures were further categorized into 27 subtypes, as listed in Fig. 2. The five most frequently performed subtypes included changing analytical column, changing trap column, calibrating MS accuracy, cleaning quadrupole, and cleaning S-lens (specific to certain Orbitrap instruments). On average, maintenance was carried out 0.6 to 5 times per month across various laboratories. The number of proteins identified varied widely across different instruments. The timsTOF Pro instrument had the highest number of protein identifications, followed by the Orbitrap series, with the TripleTOF series ranking third (Fig. 2C). The quality of these QC files was examined by 21 MS experts from 10 different participating laboratories using 15 LC-MS-related consensus metrics (Fig. 1A).

DIA-based QC is more sensitive than DDA-based QC in detecting LC-MS system faults

We first selected commonly used metrics for both DDA and DIA, encompassing both quantitative and qualitative measures such as peptide number, protein number, and MS signals. For MS signals, we used the MS1 area of targeted peptide precursors for DDA data, while the MS2 intensities of targeted peptide precursors were used for DIA files. We monitored a QE HF-X instrument for 280 days, selecting four representative time periods of 30 to 40 days each. During these periods, we analyzed various maintenance activities (Fig. 3). Each figure in Fig. 3A–D represents a specific time frame. Our data showed that while DDA and DIA metrics were generally consistent, the DIA-based QC were more sensitive in detecting various system faults. Additionally, we observed that MS1 signals from DDA were more sensitive indicators of instrument performance compared to peptide and protein identifications in DDA QC files. Similarly, MS signals in DIA files were more sensitive than peptide and protein identifications in those files. This is not unexpected, as most MS signals are not interpreted by current software. Overall, our results demonstrate that metrics from DIA files provide superior sensitivity in monitoring fluctuations across multiple LC-MS systems.

A–D Illustrates four distinct time periods, each randomly selected by the QE-HF X instrument’s longitudinal monitoring system, spanning 0 to 280 days. Each period lasts between 30 and 40 days and highlights various maintenance activities conducted during these intervals. For each time period, we selected three metrics to characterize the differences between DDA and DIA: peptide number, protein number, and MS signal. The MS signal is represented by the MS1 area from the DDA files and the MS2 intensities from the DIA files. The y-axis of each figure represents the ratio of metric values between selected raw files collected at time points n and 1. The ratio of change is calculated as follows: Ratio of change = (Yn - Y1)/Yn. The green vertical lines represent the types of instrument maintenance, which include the following four categories: a) Clean ion funnel, b) Clean quadrupole, c) Change pre-column, and d) Change analytical column. The red line indicates the performance of the current metric in DIA, while the black line represents its performance in DDA. Detailed information about the metric values is provided in the titles of each figure. For instance, in the first row of three figures, the red line represents the number of peptide identifications for DIA in each time period. Source data are provided with this paper.

Performance metric prioritization for DIA-based QC

Despite numerous proposed performance metrics in prior articles8,9,29, relatively few studies have delved into DIA-based QC30. To assemble a comprehensive set of performance metrics for evaluating DIA files, we adopted six metrics from previous publications30 and assembled 135 additional candidate metrics from papers related to DDA and selected reaction monitoring (SRM) (Fig. 4A). More details are provided in Supplementary Data 3. First, we categorized those 141 metrics into eight main groups based on the concerned sample issue and LC-MS system components: sample preparation, LC system, ion source, MS1 scan, MS2 scan, peptide and protein identification, and peptide and protein quantification, statistical analysis (Supplementary Data 3). We first removed metrics used for evaluating sample preparation that did not align with the quality control criteria of our study. Then we eliminated redundant metrics7, including those unsuitable for DIA files, such as ion injection time, TopN, and identified PSM. We also removed 14 multivariate statistics-related metrics, including MBR alignment29 that are specific to MaxQuant results, PCA analysis9, and correlation coefficient analysis9,31. We reassigned the remaining metrics to the five categories (Fig. 4B) and conducted independent evaluation for each category to ensure both the completeness and simplicity of the metrics. Since most metrics reported in the literature are specific to DDA, we also selected a few metrics from SRM-MS for evaluating DIA data.

After the above-mentioned filtering, we focused on 13 metrics. To further refine the selection, we sought input from 21 MS experts, including instrument operators, application engineers, and service engineers from analytical instrument companies including SCIEX, Thermo Fisher Scientific, and Bruker Daltonics. After discussion, the experts proposed to add two additional metrics, namely precursor ion chromatogram (PIC)32 and ion mobility accuracy to evaluate the chromatography and ion mobility specifically for diaPASEF acquired by timsTOF Pro instruments. Thereby, we assembled 15 metrics corresponding to five characteristics of the LC-MS system, including chromatography, ions source, MS1 scan, MS2 scan, identification and quantification. More details are provided in Supplementary Data 3 and Fig. 4B.

To evaluate whether these 15 metrics can capture common LC-MS system faults during maintenance, we constructed a Sankey diagram illustrating the relationship between these metrics and common instrument faults. These faults include the decline in MS2 signal and good MS1 signal with poor identification, good MS1 and MS2 signals with poor identification, similar proportional decline in MS1 and MS2 signals with poor identification, unstable spray, loss of hydrophilic peptides, loss of hydrophobic peptides, retention time shift with poor peptide identification, and poor peak shape as shown in the 1st node of Fig. 5A. Our data suggested that combinations of the 15 metrics (2nd node, Fig. 5A) can effectively detect all these LC-MS faults. For instance, the combination of F4 (charge state distribution) and F5 (intensity variation of adjacent MS1 scans) could be utilized to detect a raw file acquired with an unstable ion source spray, typically stemming from anomalies in the spray needle and fluctuations in the LC gradient flowrate (4th node, Fig. 5A). It’s worth noting that this Sankey diagram is concluded for the 20 LC instruments (Supplementary Data 1) evaluated in this study. Other types of LC instruments, such as Evosep33, are not included. We have uploaded the 15 metrics to the mzQC34 Format Specification Group from the Human Proteome Organization−Proteomics Standards Initiative (HUPO-PSI) Quality Control working group to ensure that more people are aware of and can use these metrics for quality assessment. The controlled vocabulary terms of those metrics are provided in Supplementary Data 3.

A Sankey diagram illustrates the relationship between instrument configuration issues and the metrics. Different flows are associated with various issues that contribute to a decline in instrument performance. B displays a heatmap illustrating the distribution of the 21 raters across the 21 instruments. The letters in panel (B) represent abbreviations for the experts who annotated the raw files. Panel (C) shows the observed agreement values among 11 technical replicates. Panels (D) and (E) depict the frequency of agreement among raters on 17 metrics, categorized by four and five raters’ instruments, respectively. In (D and E), the differently colored bar charts represent the proportions of the same labels for various sample sizes (2, 3, 4 or 5 people). Source data are provided with this paper.

Manual inspection of 2638 DIA QC data files using the 15 metrics

The 15 metrics were utilized to assess the performance of the 2638 DIA raw files. For reliable annotation results, 21 expert raters were recruited from 10 different institutions, including instrument operators and application engineers from manufacturers. Each DIA file underwent an independent review by four or five experts possessing extensive hands-on experience with their respective MS instruments. More details are provided in Fig. 5B. The DIA raw files were evaluated by raters and categorized as either qualified or unqualified based on the 15 metrics. In addition, raters were requested to evaluate the overall LC and MS status of each raw file, respectively, and make a conclusion of either qualified or unqualified based on their empirical overall judgment. The qualified tag indicates that the performance, although not optimal, is deemed acceptable. The 17 metrics were assessed using an inter-rater algorithm known as “observed agreement”35. The final quality label for each file was determined through a majority voting system36.

To assess the reliability of this extensive manual inspection, we randomly chose 11 DIA files from various instruments and, without informing the annotators, replicated these files twice within the entire dataset slated for annotation. This was carried out to assess the precision of the annotators’ file labeling. The median observed agreement for the technical replicates was 100%, indicating high consistency and reproducibility of this data evaluation process (Fig. 5C)35,37. Afterwards, we compiled annotation results of 2638 DIA files. Our raters demonstrated a strong consensus on metric F4 (charge state distribution), F5 (intensity variation of adjacent MS1 scans), F6 (precursor mass accuracy), F8 (fragment mass accuracy), F11 (number of identified peptides), and F12 (number of identified proteins), with consistency rates from 65% to 83% (blue bars in Fig. 5D, E). Conversely, achieving consensus on F10 (ratio of peak area of MS1 to MS2), F13 (MS1 area of targeted precursors), and F14 (MS2 intensities of targeted precursors) proved to be more challenging. Next, we employed an inter-rater algorithm termed “observed agreement” to gauge the reliability of the evaluation (Supplementary Fig. 2A). The median observed agreement across the 21 instruments ranged from 73% to 90% (Supplementary Fig. 2A and Supplementary Fig. 3), indicating that the manual inspection by 21 experts was reasonably reliable and reproducible. 73–80% of the DIA files were annotated as qualified across the majority of the 17 metrics (Supplementary Fig. 2B). The fewest faults were observed in terms of F4 (charge state distribution), F5 (intensity variation of adjacent MS1 scans), and F6 (precursor mass accuracy), since 88% to 90% of the DIA files were marked as qualified based on these three metrics.

Development of a DIA-based classifier for QC

Next, we tried to pinpoint a concise selection of peptide precursors from the mouse liver digest that exhibit robust identification across various instruments. We generated 221 liver digests as biological replicates from four mice. These were subsequently analyzed in DIA mode in seven cohorts using four types of mass spectrometers. Using DIA-NN and an in-house built spectral library, we identified 176,304 peptide precursors, with missing values ranging from 50% to 66%. Based on the inclusion criteria outlined in Fig. 6A, we narrowed our focus to peptide precursors that were consistently expressed across all DIA files, with appropriate length and no missed cleavage. We additionally excluded peptides containing reactive residues like methionine and N-terminal glutamine, along with those featuring inhibitory motifs for trypsin, such as Lys-Lys and Arg-Arg following previous publication38. We also manually inspected each of these peptide precursors using Skyline to verify their quality, particularly in terms of transition peak shape. This process boiled down to 934 high-quality peptide precursors. The physicochemical properties of these peptide precursors are illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 4. Ninety percent of the peptide precursors consist of 7 to 15 amino acids, with the GRAVY value39 of the 934 peptide precursors ranging from −2.5 to 2.3. Mean retention time of the 934 peptide precursors corresponds to 90% of the elution time across datasets. Intensities of the remaining peptide precursors span 3.5 to 4 orders of magnitude. The 934 peptide precursors were used for the development of subsequent classifier.

A Workflow for selecting peptide candidates. B Workflow for developing the classifier, including training, and testing of the LC and MS models using 20 features based on the XGBoost algorithm. C Importance distribution of the 20 features in the LC model. D Importance distribution of the 20 features in the MS model. E Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for the LC model with three features in the 1st validation dataset. F ROC curves for the MS model with 12 features in the 1st validation dataset. G ROC curves for the LC model with three features in the 2nd validation dataset. H ROC curves for the MS model with 12 features in the 2nd validation dataset. I Physicochemical properties of the 33 peptides selected both in the LC and MS models. In figures (E–H), the differently colored lines represent the AUC curves for various features across the models. Source data are provided with this paper.

Subsequently, the 2638 DIA files were analyzed using DIA-NN and an in-house built spectral library for mouse liver, leading to identification of a total of 220,514 peptides from 11,970 proteins (Supplementary Fig. 1B; Fig. 2C). Among the four TripleTOF series instruments, a median of 2916 proteins were identified. The 13 Orbitrap series instruments identified a median of 4381 proteins, while four timsTOF Pro instruments identified a median of 6070 proteins. As expected, the data from each instrument were well resolved in t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding40 (t-SNE) plot (Supplementary Fig. 5). This indicates that relying solely on data dimensionality reduction analysis to differentiate the quality among different instruments poses challenges. Conversely, t-SNE analysis of the data acquired by a particular instrument at various time points exhibited no obvious batch effects, indicating that the data from a specific MS instrument can be considered comparable (Supplementary Fig. 6).

These files were then divided into a training set containing 2110 DIA files, and a validation set (n = 528) (Fig. 6B). Based on the training set, we extracted the precursor-related features (F2, F13 and F14) of the 934 peptide precursors, along with the DIA raw file-based features (F1, F3 ~ F12), prior to applying XGBoost-based machine learning algorithms41 with five-fold cross-validation. To ensure that our selected features could be practically measured following QC sample acquisition, we constrained the number of features to twenty or fewer. A panel of 19 peptide precursors along with F3 achieved the optimal accuracy in distinguishing qualified and unqualified DIA files at the LC level (Fig. 6C), while another panel composed of 14 peptide precursors, along with F4, F5, F6, F7, F11, and F12, achieved the highest accuracy in segregating qualified and unqualified DIA files at the MS level (Fig. 6D). The contribution of each feature to the LC and MS classifiers was subsequently evaluated using the SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) algorithm (Figs. 6C, D). We further evaluated the performance of the LC and MS models using the validation dataset containing 528 DIA files. The annotations were blinded during feature extraction and machine learning model development, ensuring an unbiased evaluation. The receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) plot for these independent test sets, using the 20 independent features for LC and MS quality control, yield an area uner curve (AUC) of 0.91 for the LC model (Fig. 6E) and an AUC of 0.97 for the MS model (Fig. 6F).

To further validate the machine learning features, we additionally used 116 DIA datasets collected by a QE HF instrument from December 2023 to August 2024 for quality control. During these eight months, the QE HF instrument conducted QC twice a week using a 30-minute DIA method with an effective LC gradient during normal operation, and additional QC data were collected before and after any instrument malfunctions. The identified proteins in those 116 DIA files ranged from 1983 to 4794 with a median of 4634 proteins (Supplementary Fig. 7A). We invited three experts to annotate 116 raw files based on the 14 aspects mentioned previously in the article. The observed agreement among each pair of experts ranged from 0.85 to 0.87 (Supplementary Fig. 7B), indicating a good level of consistency. For most metrics, our raters demonstrated a consensus, with consistency rates between 82% and 99% (Supplementary Fig. 7C). To improve the consistency and accuracy of high-quality labels while minimizing the bias or errors of individual reviewers, we applied the principle of majority rule in determining the final labels. Ultimately, 68% to 99% of the files were classified as qualified across most of the 16 metrics (Supplementary Fig. 7D). The ROC plot for these independent test sets, utilizing 20 independent features for the LC and MS systems, yielded an AUC of 0.78 for the LC model (Fig. 6G) and an AUC of 0.94 for the MS model (Fig. 6H). These results demonstrate that the model is highly effective and practical for monitoring LC-MS instruments.

To test the stability of these 33 selected peptide precursors in real-world applications, we conducted additional experiments to monitor them over time. We analyzed a WMLD sample using DIA in a TripleTOF 5600+ over 31 days. The retention time, GRAVY value and coefficient of variation (CV) of peptide precursors are shown in Fig. 6I. The two panels had no overlapped peptide precursors, suggesting each of them captures unique characteristic of the LC and MS system. Their retention time values spanned from 7.67 to 33.07 min, while the GRAVY values ranged from −1.97 to 1.83, indicating a diverse distribution of hydrophilic and hydrophobic properties. All except one peptide precursor exhibited a CV lower than 5.8%. The highest CV was 11.2%. The median CV was 2.9%, while the mean CV was 3.5%. The data strongly indicate that these peptides are consistently detected over time, thus enabling the derivation of reliable QC metrics.

iDIA-QC software tool for quality control evaluation of DIA files

Finally, we built a software tool called iDIA-QC to automate the thus described QC and troubleshooting. The metric extraction process within the software depends on two independent software tools, namely msConvert and DIA-NN. Specifically, msConvert was utilized for extracting F3 and F5, F15 was obtained from MGF files acquired with timsTOF Pro instrument, and the remaining metrics were extracted using DIA-NN (Supplementary Fig. 8). Given a 30-min DIA analysis of the mouse liver digest, iDIA-QC outputs a comprehensive report of the 17 metrics based on a machine learning models for assessing the LC and MS. The tool not only reports whether the LC and MS systems are qualified, but also provides guidance pinpointing the potential cause of the faults as exemplified in Fig. 5A.

Discussion

Quality control for quantitative MS-based proteomics is predominantly conducted using DDA and SRM/MRM analyses of certain QC samples. In 2010, Rudnick et al.7 proposed 46 system performance metrics which are currently the most comprehensive scheme for QC and widely adopted by the community in integrative computational modeling8,9. However, they lack essential information for evaluating MS2-based quantitation of peptide precursors. This could be attributed to the fact that the paper was published before DIA-MS prevailed in quantitative proteomics17. Xuan et al.30 discussed six metrics used for evaluating the MS instrument status based on the DIA files when they presented the MS1-based DIA workflow. However, the community still lacks a comprehensive investigation of QC for DIA experiments which require more rigorous performance for both MS1- and MS2-based quantitation of peptide precursors. The SRM-based QC software tools are more rigorous in terms quantitative proteomics, however, it cannot be directly applied to large scale quantitative proteomics experiments concerning thousands of peptide precursors15,16,42.

The first contribution of our study is the demonstration that DIA-MS is more sensitive and precise indication of the quality of LC and MS systems. Moreover, we generated the so-far most well-designed and comprehensive QC data sets using both DDA-MS and DIA-MS in multivendor LC and MS instruments over a period of 125 weeks in different laboratories. We further recruited 21 LC-MS experts to annotate the resultant 2754 DIA files. In addition, we compiled over 140 potentially informative QC metrics, and, through group efforts, narrowed down to 15 practically applicable metrics. Some of the metrics, for instance that evaluating ion mobility, have not been reported before.

While various QC samples are being used in different laboratories, we proposed a mouse liver digest sample, which is relatively abundant and cheap, from which we proposed two peptide precursor panels which are robustly measurable in all the MS instruments used in our study. With two machine learning models, the performance of LC and MS can be reliably predicted (AUC values is higher than 91% in independent validation set). The models are condensed in a convenient software tool called iDIA-QC. To the best of our knowledge, this is the primary software tool which not only evaluates the quality of a raw DIA file, but also offers guidance to the potential causes (Fig. 5).

Of the 15 prioritized QC metrics, only three are peptide precursors from mouse liver digests, while the remaining 12 are generic metrics independent of the mouse sample. This suggests that the workflow could potentially be applied to various QC and experimental samples, though further investigation is needed to fully generalize its application. While our study covers a broader range of commonly used instrument types in the participating laboratories, it is not possible to include all LC and MS instruments, particularly those emerging new instruments. However, we think it won’t be too difficult to extend the metrics, the standard operating procedures, the computational models, and the software tool, as established here, to evaluate the performance of additional instruments.

In conclusion, we established a strategy to adopt DIA-MS for QC of MS-based quantitative proteomics experiments. All the potentially informative QC metrics have been investigated in a comprehensive manually curated QC dataset. We proposed two machine learning models to evaluate the performance of various LC and MS systems and present a software tool, namely iDIA-QC, for automated QC and troubleshooting of LC-MS instruments.

Methods

Preparation of mouse liver digest

Fresh frozen mouse liver tissues were harvested from six C57BL/6 J mice (3 males and 3 females), with the approval of the Animal Care and Ethics Committee of Westlake University (No. 2019-027-GTN). Pressure cycling technology (PCT)28,43 based preparation methods were used for mouse liver tissue lysis and protein digestion respectively44. Unless otherwise noted, all reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. For PCT-based sample preparation, sample lysis and protein digestion were performed using the PCT workflow28,43. In brief, 1 mg of each mouse liver sample was weighed and reconstituted in a lysis buffer containing 6 M urea and 2 M thiourea in 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate (ABB) with a pH of 8.5, The sample was then transferred to a PCT-MicroTube for subsequently PCT-assisted tissue lysis. Next, add 5 µL of a 100 mM Tris(2-carboxyethyl)- phosphine (TCEP) solution (final concentration 10 mM) and 2.5 µL of an 800 mM iodoacetamide solution (final concentration 40 mM) to facilitate reduction and alkylation. Following this, 75 µL of a 100 mM ABB solution was added to each PCT-MicroTube. Lys-C was incorporated at an enzyme-to-substrate ratio of 1:80 (wt/wt), and trypsin at a ratio of 1:20 (wt/wt) to initiate protein digestion. Tissue lysis, reduction, alkylation, and protein digestion were conducted using the Barocycler NEP2320-45K (Pressure Biosciences Inc., MA). The tryptic peptides were cleaned using Sep-Pak C18 1cc Vac Cartridge (Waters, MA). Finally, the peptide solutions were pooled, aliquoted into tubes, lyophilized into powder, and stored at −80 °C for subsequent analysis.

DIA library construction

We constructed three mouse liver-specific spectral libraries for two MS vendors, and a published mouse spectral library45 to analyzed the 2754 DIA files. About 200 µg of mouse liver digests were initially separated and fractionated using a Thermo Scientific UltiMateTM 3000 RSLC LC system equipped with a reversed-phase LC into 90 fractions, then combined into 30 fractions using a specific strategy and evaporated and resuspended for next analysis. Each fraction was injected and trapped on an Acclaim PepMap RSLC C18 column, followed by elution using a linear ramping gradient. The analysis was conducted using the UltiMateTM 3000 RSLCnano LC system from Thermo Fisher Scientific, coupled with QE-HF X and a nanoElute system from Bruker Daltonics, which was coupled with the timsTOF Pro instrument.

FragPipe computation platform (version 13), incorporating with MSFragger46 (version 2.4) and Philosopher47 (version 3.2.5) components, was employed to generate three spectral libraries for FAIMS-DIA, DIA and diaPASEF48 analysis of mouse liver tissues. The FragPipe software searched a mouse Swiss-Prot FASTA database against all DDA files, encompassing 20,269 protein sequences (downloaded on May 21, 2021), with default settings.

For DIA files produced by TripleTOF series instruments, a previously established spectral library containing 110,126 precursors and 10,542 protein groups was utilized45. The spectral library used to analyze the data generated from the Orbitrap instruments without FAIMS contains 161,081 peptide precursors from 8513 protein groups, while the libraries for FAIMS-Exploris 480 and timsTOF Pro contain 154,452 peptide precursors from 8593 protein groups and 305,630 peptide precursors from 9488 protein groups, respectively.

DDA-MS analysis

The FragPipe computational platform (version 14), incorporating MSFragger (version 3.1.1), Philosopher (version 3.2.5), and IonQuant (version 1.4.4) components, was utilized for the analysis of the DDA files. The mouse Swiss-Prot FASTA database (downloaded on May 21, 2021), comprising 20,269 protein sequences, was queried, permitting a maximum of two missed cleavages. Cysteine carbamidomethyl was established as a fixed modification, while methionine oxidation was designated as a variable modification. We opted for comprehensive identification and false discovery rate (FDR) analysis, with an FDR threshold set at 1%.

DIA-MS analysis

We used DIA-NN (v1.7.15)49 to analyze data acquired through various data-independent acquisition methods, encompassing FAIMS-DIA and DIA files acquired from Orbitrap instruments with and without FAIMS devices, SWATH files from TripleTOF series instruments, and diaPASEF files from timsTOF Pro instruments. We applied a data filtration criterion of 1% FDR at both peptide precursor and protein levels and configured the quantification strategy to robust LC (high accuracy) mode. All 2754 DIA files analyzed in the study have been uploaded to Proteomics IDEntifications database (PRIDE).

Description of the 15 metrics

The 15 metrics can be divided into five sections: liquid chromatography, ion source, MS1 scan, MS2 scan, and the identification and quantification of peptides and proteins. The names of these 15 metrics are shown in Fig.4B.

LC-MS sample analysis was evaluated using three key metrics. The first metric, peak width (FWHM), assesses column performance, with wider peaks indicating decreased performance, especially for hydrophobic peptides. Sharper peaks produce higher signal intensities and improve the signal-to-noise ratio, increasing the number of identified peptides. The second metric, retention time of targeted precursors, measures the elution time and order of targeted peptide precursors, allowing for comparison between raw files. The third metric, precursor ion chromatogram (PIC), provides comprehensive information on peptide elution, with a focus on hydrophilic and hydrophobic peptides. The number of MS1 signals from the 2754 DIA files showed varying distributions due to differences in LC-MS systems. Consequently, the MS1 scan was scaled using linear interpolation50, generating 1000 additional data points within the existing range.

The fourth metric, charge state distribution, is crucial for peptide identification. Charge state distribution can vary based on peptide length, composition, and experimental ionization conditions. By monitoring this distribution, we can assess the quality of peptide identification and identify potential factors affecting result accuracy. The fifth metric, intensity variation of adjacent MS1 scans, is a critical factor in achieving reliable and reproducible mass spectra. It is monitored by analyzing the ratio of MS1 total ion current between adjacent MS1 scans. By tracking the frequency of changes in MS1 intensity, we can detect issues with electrospray stability and take corrective actions to ensure data reliability. Factors such as sample quality, spray needle condition, and the applied voltage of the ion source can impact electrospray stability, leading to inconsistent results.

The sixth metric, precursor mass accuracy, was extracted from the DIA-NN mainoutput. Mass shifts can be caused by various factors such as temperature, airflow, or instrument calibration. The seventh metric, TIC MS1 signal, was obtained by integrating the MS1 chromatogram profile. This signal can be influenced by contamination on the MS front-end, retention time shifts, or loss of hydrophilic/hydrophobic peptides. While comparability between raw files from different instrument types is limited, data from the same instruments can be used to assess consistency with this parameter. Metric 15 evaluates the ion mobility accuracy of a standard sample with an m/z of 622.0290, featuring a reduced ion mobility coefficient (1/K0) of 0.9915, as extracted from diaPASEF files. The standard sample, ESI-L Low Concentration Tuning Mix from Agilent, was introduced into the ion source filter of the timsTOF Pro instrument. This metric is specifically designed for analyzing raw files generated by timsTOF Pro instruments. The eighth metric evaluates the mass accuracy of identified peptide fragment ions, extracted from the DIA-NN mainoutput.stats.tsv file. The ninth metric quantifies TIC MS2 signal, obtained by integrating the MS2 chromatogram profile. Several factors, such as contamination at the MS front-end and fragmentation efficiency, can adversely affect the MS2 signal. The tenth metric, which represents the ratio of the peak area of the MS1 signal to the MS2 signal, was introduced to distinguish between these two issues. This ratio is calculated by dividing the value of the metric seven by that of the metric nine. Together, the metric seven, metric nine and metric ten enable a more precise identification of the underlying factors affecting MS performance.

Metrics 11 and 12 reflect the number of identified peptides and proteins, respectively. These values are obtained by matching MS2 spectra to those in a spectral library and are extracted from the DIA-NN mainoutput. Several factors can influence the results of these metrics, including the peak width and retention time distribution during chromatography, as well as the TIC MS1 and MS2 signals. Additionally, metrics 13 and 14 provide the MS1 area and MS2 intensities of targeted peptide precursors, respectively, also extracted using DIA-NN. Unlike metric seven and metric nine, metrics 13 and 14 offer detailed insights into changes in targeted peptide precursors based on their varying physicochemical properties and signal characteristics.

Metrics 3 and 5 are extracted from mzXML files, while metric 15 is derived from MGF files from timsTOF Pro instruments. The remaining metrics are sourced from DIA-NN result files. Details on the sources of all metrics can be found in Supplementary Data 3.

Machine learning

The datasets acquired from 21 instruments were used to develop and validate the XGBoost model, including both the discovery and test datasets. Model building comprised three steps, data preprocessing, model training, and testing. During data preprocessing, features with high missing rates ( > 70% NA) were removed, and other missing values were imputed by the minimum of each respective feature. Data preprocessing was performed using the ‘pandas’ library in Python. During model training, the discovery dataset was used to develop the model, and the test dataset was utilized for model evaluation. In machine learning, the importance of peptide features is determined by summing up the importance of corresponding F2, F13, and F14 metrics of the peptide precursors. Furthermore, the evaluation metric was set to the AUC. ROC) curves and AUCs were generated to assess the model performance with the Proc package.

Development of iDIA-QC software

The complete algorithmic process of iDIA-QC consists of four steps, as depicted in Supplementary Fig. 8. Firstly, the. d /.raw /.wiff files were converted to mzXML format using the msConvert software. Subsequently, the DIA files were analyzed using DIA-NN (v1.7.15) to derive peptide and protein quantification results. Secondly, numerical metrics were extracted from each DIA raw file using the mzXML files and DIA analysis results obtained from DIA-NN. Thirdly, we fed the metric extraction results into a machine learning model, which assigns an evaluation result (qualified or unqualified) to each metric, generating a performance assessment for both LC and MS across all evaluated aspects.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis of the data was performed using R software (version 4.1.2), which included the use of heatmap, t-SNE, observed agreement, and R package plot functions. The proteins in the heatmaps were hierarchically clustered using the centroid method for each instrument. The CV was calculated by dividing the standard deviation by the mean.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

iDIA-QC is developed in Python and is freely available. The latest software version is available at https://github.com/guomics-lab/iDIA-QC. The mass spectrometry raw data and spectral libraries generated and analyzed during the current study have been deposited with the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE51 partner repository. Specifically, the training set and retrospective dataset, which include 2638 files, have been deposited in the PRIDE under dataset identifier PXD051878, while the prospective dataset, containing 116 files, is stored under identifier PXD055173. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Code relevant to data analysis in this study is available at https://github.com/guomics-lab/iDIA-QC.

References

Domon, B. & Aebersold, R. Options and considerations when selecting a quantitative proteomics strategy. Nat. Biotechnol. 28, 710–721 (2010).

Xiao, Q. et al. High-throughput proteomics and AI for cancer biomarker discovery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 176, 113844 (2021).

Aebersold, R. & Mann, M. Mass-spectrometric exploration of proteome structure and function. Nature 537, 347–355 (2016).

Mann, M. Comparative analysis to guide quality improvements in proteomics. Nat. Methods 6, 717–719 (2009).

Bittremieux, W. et al. Quality control in mass spectrometry-based proteomics. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 37, 697–711 (2018).

Bittremieux, W., Valkenborg, D., Martens, L., Laukens, K. Computational quality control tools for mass spectrometry proteomics. Proteomics 17 https://doi.org/10.1002/pmic.201600159 (2017).

Rudnick, P. A. et al. Performance Metrics for Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry Systems in Proteomics Analyses. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 9, 225–241 (2010).

Ma, Z.-Q. et al. QuaMeter: Multivendor Performance Metrics for LC MS/MS Proteomics Instrumentation. Anal. Chem. 84, 5845–5850 (2012).

Wang, X. et al. QC Metrics from CPTAC Raw LC-MS/MS Data Interpreted through Multivariate Statistics. Anal. Chem. 86, 2497–2509 (2014).

Matzke, M. M. et al. Improved quality control processing of peptide-centric LC-MS proteomics data. Bioinformatics 27, 2866–2872 (2011).

Amidan, B. G. et al. Signatures for Mass Spectrometry Data Quality. J. Proteome Res. 13, 2215–2222 (2014).

Bittremieux, W., Meysman, P., Martens, L., Valkenborg, D. & Laukens, K. Unsupervised Quality Assessment of Mass Spectrometry Proteomics Experiments by Multivariate Quality Control Metrics. J. Proteome Res. 15, 1300–1307 (2016).

Bittremieux, W., Kelchtermans, P., Valkenborg, D., Martens, L. & Laukens, K. jqcML: An Open-Source Java API for Mass Spectrometry Quality Control Data in the qcML Format. J. Proteome Res. 13, 3484–3487 (2014).

Walzer, M. et al. qcML: An Exchange Format for Quality Control Metrics from Mass Spectrometry Experiments. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 13, 1905–1913 (2014).

Bereman, M. S. et al. Implementation of Statistical Process Control for Proteomic Experiments Via LC MS/MS. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 25, 581–587 (2014).

Bereman, M. S. et al. An Automated Pipeline to Monitor System Performance in Liquid Chromatography Tandem Mass Spectrometry Proteomic Experiments. J. Proteome Res. 15, 4763–4769 (2016).

Gillet, L. C. et al. Targeted Data Extraction of the MS/MS Spectra Generated by Data-independent Acquisition: A New Concept for Consistent and Accurate Proteome Analysis Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 11 https://doi.org/10.1074/mcp.O111.016717 (2012).

Guo, T. et al. Rapid mass spectrometric conversion of tissue biopsy samples into permanent quantitative digital proteome maps. Nat. Med. 21, 407–413 (2015).

Zhu, Y., Aebersold, R., Mann, M. & Guo, T. SnapShot: Clinical proteomics. Cell 184, 4840–4840 e4841 (2021).

Niu, L. et al. Noninvasive proteomic biomarkers for alcohol-related liver disease. Nat. Med. 28, 1277–1287 (2022).

Cai, X. et al. Population serum proteomics uncovers a prognostic protein classifier for metabolic syndrome. Cell Rep. Med 4, 101172 (2023).

Sun, Y. et al. Artificial intelligence defines protein-based classification of thyroid nodules. Cell Discov. 8, 85 (2022).

Sun, R. et al. Proteomic Dynamics of Breast Cancer Cell Lines Identifies Potential Therapeutic Protein Targets. Mol. Cell Proteom. 22, 100602 (2023).

Guo, T. et al. Quantitative Proteome Landscape of the NCI-60 Cancer Cell Lines. iScience 21, 664–680 (2019).

Derks, J. et al. Increasing the throughput of sensitive proteomics by plexDIA. Nat. Biotechnol. 41, 50–59 (2023).

Rosenberger, F. A. et al. Spatial single-cell mass spectrometry defines zonation of the hepatocyte proteome. Nat. Methods 20, 1530–1536 (2023).

Gao, H. et al. Accelerated Lysis and Proteolytic Digestion of Biopsy-Level Fresh-Frozen and FFPE Tissue Samples Using Pressure Cycling Technology. J. Proteome Res. 19, 1982–1990 (2020).

Cai, X. et al. High-throughput proteomic sample preparation using pressure cycling technology. Nat. Protoc. 17, 2307–2325 (2022).

Bielow, C., Mastrobuoni, G. & Kempa, S. Proteomics Quality Control: Quality Control Software for MaxQuant Results. J. Proteome Res. 15, 777–787 (2016).

Xuan, Y. et al. Standardization and harmonization of distributed multi-center proteotype analysis supporting precision medicine studies. Nat. Commun. 11, 5248 (2020).

Lu, C. et al. Longitudinal Large-Scale Semiquantitative Proteomic Data Stability Across Multiple Instrument Platforms. J. Proteome Res. 20, 5203–5211 (2021).

Wang, N. & Li, L. Exploring the Precursor Ion Exclusion Feature of Liquid Chromatography Electrospray Ionization Quadrupole Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry for Improving Protein Identification in Shotgun Proteome Analysis. Anal. Chem. 80, 4696–4710 (2008).

Bache, N. et al. A Novel LC System Embeds Analytes in Pre-formed Gradients for Rapid, Ultra-robust Proteomics. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 17, 2284–2296 (2018).

Bittremieux, W. et al. The Human Proteome Organization-Proteomics Standards Initiative Quality Control Working Group: Making Quality Control More Accessible for Biological Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 89, 4474–4479 (2017).

Salminen, J. O., Al-Merekhi, H. A., Dey, P. & Jansen, B. J. Inter-Rater Agreement for Social Computing Studies. In 2018 Fifth International Conference on Social Networks Analysis, Management and Security (SNAMS), 80–87 https://doi.org/10.1109/SNAMS.2018.8554744 (2018).

Penrose, L. S. The Elementary Statistics of Majority Voting. J. R. Stat. Soc. 109, 53–57 (1946).

Landis, J. R. & Koch, G. G. The Measurement of Observer Agreement for Categorical Data. Biometrics 33, 159–174 (1977).

Hoofnagle, A. N. et al. Recommendations for the Generation, Quantification, Storage, and Handling of Peptides Used for Mass Spectrometry-Based Assays. Clin. Chem. 62, 48–69 (2016).

Gasteiger, E. et al. Protein Identification and Analysis Tools on the ExPASy Server. In The Proteomics Protocols Handbook, Walker, J. M. Ed.; Humana Press, (2005); 571-607.

Song, W., Wang, L., Liu, P. & Choo, K.-K. R. Improved t-SNE based manifold dimensional reduction for remote sensing data processing. Multimed. Tools Appl. 78, 4311–4326 (2019).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, California, USA; (2016).

Bereman, M. S. Tools for monitoring system suitability in LC MS/MS centric proteomic experiments. PROTEOMICS 15, 891–902 (2015).

Zhu, Y. et al. High-throughput proteomic analysis of FFPE tissue samples facilitates tumor stratification. Mol. Oncol. 13, 2305–2328 (2019).

Glatter, T. et al. Large-Scale Quantitative Assessment of Different In-Solution Protein Digestion Protocols Reveals Superior Cleavage Efficiency of Tandem Lys-C/Trypsin Proteolysis over Trypsin Digestion. J. Proteome Res. 11, 5145–5156 (2012).

Krasny, L. et al. A mouse SWATH-mass spectrometry reference spectral library enables deconvolution of species-specific proteomic alterations in human tumour xenografts. Dis. Models Mechanisms 13, dmm044586 (2020).

Kong, A. T., Leprevost, F. V., Avtonomov, D. M., Mellacheruvu, D. & Nesvizhskii, A. I. MSFragger: ultrafast and comprehensive peptide identification in mass spectrometry based proteomics. Nat. Methods 14, 513–520 (2017).

da Veiga Leprevost, F. et al. Philosopher: a versatile toolkit for shotgun proteomics data analysis. Nat. Methods 17, 869–870 (2020).

Demichev, V. et al. dia-PASEF data analysis using FragPipe and DIA-NN for deep proteomics of low sample amounts. Nat. Commun. 13, 3944 (2022).

Demichev, V., Messner, C. B., Vernardis, S. I., Lilley, K. S. & Ralser, M. DIA-NN: neural networks and interference correction enable deep proteome coverage in high throughput. Nat. Methods 17, 41–44 (2020).

Blu, T., Thavenaz, P. & Unser, M. Linear interpolation revitalized. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 13, 710–719 (2004).

Vizcaíno, J. A. et al. 2016 update of the PRIDE database and its related tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 11033–11033 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by grants from the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2022YFF0608403, 2021YFA1301600, 2022YFF0608404, and 2020YFE0202200), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82073529, 81903316), the “Pioneer” and “Leading Goose” R&D Program of Zhejiang (2024SSYS0035, 2023C03056), and the Westlake Educational Foundation. Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 8 are created with Biorender.com. We thank the Westlake University Supercomputer Center for their assistance in data analysis and storage. This study is also partly supported by the π-CLIP (π-HuB Clinical Proteomics) workgroup in the π-HuB consortium.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.G., Y.Z., and H.G. designed the project. H.W. completed parts of data analysis. H.G., D.W., G.W., S.L., Y.X., W.J., Z.D., X.W., M.L., M.C., H.F., Q.Z., J.T., Z.S., J.X., S.L., C.C., X.Liu, X.Lyu, Z.G., Y.Q., R.W., X.D., T.T., F.K., L.H., and M.W., generated or annotated the raw files using various mass spectrometers. H.G., and Z.N., designed the iDIA-QC.exe offline software. H. G. and T.G. wrote the manuscript. Y.Z., D.W., L.Q., Y.S., Y.Z., and X.D., modified the manuscript. T.G. and F.H. supervised this project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

T.G. and Y. Zhu are shareholders of Westlake Omics Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Three patents related to iDIA-QC technologies have been filed. Two have been granted, with the numbers CN 114858958 B and CN 116106464 B, while the third is currently pending, with the application number CN 202210783026.2. Y.L., Z.N. and Y.L. are employees of Westlake Omics Inc. H.F. and M.C. are employees of Shanghai Luming Biological Technology Inc. Q.F. and J.T. are employees of Shanghai Applied Protein Technology co. ltd. C.C., X.L., X.L. and F.K. were employees of SCIEX China during this project. Z.G., Y. Q. and T.T. are employees of Thermo Fisher Scientific China while R.W., X.D., L.M. and M.W. are employees of Bruker Daltonics China. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Liang Qiao, and David Tabb for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, H., Zhu, Y., Wang, D. et al. iDIA-QC: AI-empowered data-independent acquisition mass spectrometry-based quality control. Nat Commun 16, 892 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54871-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54871-1