Three years ago, David Stover, Ben Kneppers and Kevin Ahearn quit their jobs in finance and co-founded Bureo, a Los Angeles-based company that makes skateboards and sunglasses from recycled nylon.

The three friends stumbled onto the idea while surfing. “We kept seeing all this trash,” Stover says. “When we researched ocean waste, we learned that there’s a constant stream of nylon fishing nets being dumped into the ocean every year, nets that are just going to sit there for generations. This stuff doesn’t break down.”

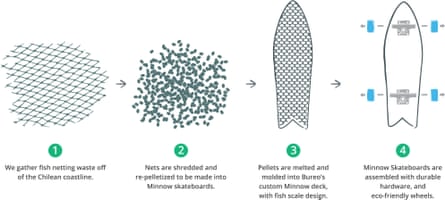

The trio launched a Kickstarter campaign and each contributed $5,000 to the new venture. Today, the company pays fishermen in Chile to collect old nylon fishing nets, which are then recycled into skateboards and sunglasses.

Nylon, a synthetic fiber made of polymers, doesn’t break down easily and accounts for about 10% of the debris in the ocean . According to the World Society for the Protection of Animals, more than 600,000 tons of fishing gear is dumped into oceans every year, including nylon nets. Fishermen often discard the nets because the alternative is paying someone to dispose of them properly.

Nylon isn’t just found in fishing nets. It’s also in clothing, carpets and packaging. It was first introduced at the New York World’s Fair in 193 9 in the form of women’s tights, but the fiber really took off after second world war. Prior to 1945, cotton and wool dominated the market, but by the end of the war, synthetic fibers like nylon had eaten up 25% of the market share, and could be found in military supplies such as parachutes, ropes, tents and uniforms.

The economics of recycling nylon are not very appealing, however . Stephen Johnston, an associate professor in plastic engineering at the University of Massachusetts Lowell, ran a research program on recycled fishing nets for Bureo. Nylon, he says, is not an easy or cheap material to recycle. Plus polymers, or plastics, are cheap to buy new which may be why many companies choose to use polyethylene terephthalate (PET) – the most common type of plastic found in soda and water bottles – instead .

Contamination is another concern. Unlike metals and glass, which are melted at high temperatures, nylon is melted at a lower temperature, meaning some contaminants – non-recyclable materials and microbes or bacteria – can survive. This is why all nylons have to be cleaned thoroughly before the recycling process. “When you’ve dragged a fishing net through a boat, on the ocean floor, and wherever else, it’s a lot harder to clean before you can recycle it,” Johnston says.

That’s why Johnston is supportive of circular economy business models, in which businesses keep resources in use for as long as possible, extract their maximum value and then recycle and reuse products and materials. “What would change the recycling scene is if we were charged per pound for all waste. Or if companies had to take back part of what they produced.”

Bureo has pounced on that idea already: the company’s sunglasses come with a lifetime warranty. Bureo will fix any pair of glasses free of charge, or provide customers with new frames if their product is beyond repair. Old frames are recycled.

Italian manufacturer Aquafil is also eating its own product, as it were – in this case, it’s nylon fibers used in their carpets. Giulio Bonazzi, CEO of Aquafil, says that after nearly 40 years of producing carpet yarn, a growing awareness of the environmental harm caused by synthetic materials made him want to turn towards a more environmentally friendly business model.

In 2007, Aquafil began developing a machine that can churn through most kinds of nylons, producing new threads ready to be repurposed. Aquafil now sells these threads, called Econyl, to American brands such as Outerknown, an LA-based outerwear company started by pro surfer Kelly Slater, and swimwear giant Speedo.

LA-based Masami Shigematsu works on product development for Speedo. She says that she had been actively searching for recycled nylon for years before she found Econyl. “It has to perform well. It can’t just be a sustainable material. Our products are being used by athletes who need it to function as good as new material.”

In 2014, Shigematsu met with Aquafil and started experimenting with the fabric. Last year, Speedo rolled out two products with Econyl and has since expanded to include more than 50 products made with the material.

California-based Patagonia has also been adding more recycled nylon to its lineup. Currently, the company has more than 50 products that contain recycled nylon in various percentages, says Matt Dwyer, material innovation manager at the company’s headquarters in Ventura. The Torrentshell jackets, for instance, have an outer layer textile made with 100% chemically recycled nylon.

The nylon journey, according to him, is similar to polyester: it took Patagonia nearly 15 years to develop the technology to recycle polyester to a point where it was as good as virgin polyester.

“The key is to make sure that the math is good – that the energy balance for implementing a new recycled material is truly better than a virgin one, and that the quality and performance meet our standards,” says Dwyer.

Patagonia wants to go further than just use recycled nylon in its products: through the company’s $20 Million and Change fund, it has also invested in Bureo.

“This is really the future of manufacturing,” says Stover. “We have to start reassessing waste as value. And Patagonia gets that. Nylon is just one material in our lives. Imagine if we did this for all the materials we use. ”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion