-

-

Chemicals that have a toxic effect on human gut bacteria include pesticides, like herbicides and insecticides, that are sprayed onto food crops. These chemicals stifle the growth of gut bacteria thought to be vital for health. Credit: Ailen Fernandez-Lande/ University of Cambridge

Chemicals that have a toxic effect on human gut bacteria include pesticides, like herbicides and insecticides, that are sprayed onto food crops. These chemicals stifle the growth of gut bacteria thought to be vital for health. Credit: Ailen Fernandez-Lande/ University of Cambridge -

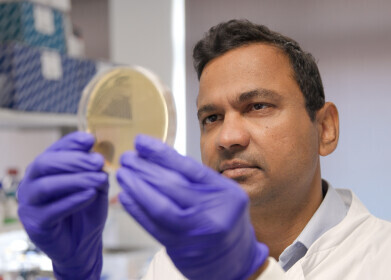

Patil says the study has provided the data to predict the effects of new chemicals, with the aim of moving to a future where new chemicals are safe by design. Credit: Jonathan Settle/University of Cambridge

Patil says the study has provided the data to predict the effects of new chemicals, with the aim of moving to a future where new chemicals are safe by design. Credit: Jonathan Settle/University of Cambridge -

Roux was surprised to find that many industrial chemicals we're regularly in contact with affect human gut bacteria, even though they weren’t previously thought to affect living organisms at all. Credit: Jonathan Settle/University of Cambridge

Roux was surprised to find that many industrial chemicals we're regularly in contact with affect human gut bacteria, even though they weren’t previously thought to affect living organisms at all. Credit: Jonathan Settle/University of Cambridge

News

Chemicals widely in everyday use found to be harmful to gut microbiome; drive antibiotic resistance

Dec 03 2025

A University of Cambridge study has identified 168 everyday chemicals that are toxic to beneficial gut bacteria and can promote antibiotic resistance, raising difficult questions for regulators’ assessment of pesticides, plastics and industrial compounds

A large-scale laboratory screen of human-made chemicals has identified 168 compounds that are toxic to bacteria found in the healthy human gut. The work, led by the University of Cambridge, UK, has shown that many chemicals present in food, water and the wider environment can stifle the growth of gut microbes that are thought to be vital for human health.

The study considered 1,076 chemical contaminants against 22 representative species of gut bacteria under controlled laboratory conditions. Many of the chemicals – which people encounter through dietary and environmental exposure – were not previously thought to affect bacteria at all. The findings suggest that everyday chemical pollution has a direct effect on the composition and function of the human gut microbiome.

The researchers reported that, as some bacteria adjust to resist chemical pollutants, they simultaneously acquire resistance to antibiotics such as ciprofloxacin. If similar processes occur in the human gut, exposures to these chemicals could make common infections harder to treat and contribute to the wider crisis in antimicrobial resistance.

The work focused on chemicals in routine use, including pesticides such as herbicides and insecticides applied to crops, as well as industrial chemicals used in flame retardants and plasticisers. These substances can enter the body through residues on food, contaminated water, household dust or direct contact with treated materials. Many of them have regulatory approval because they have appeared safe for human cells and target only specific organisms, such as insects or fungi.

Dr Kiran Patil talks about his work at Cambridge

The human gut microbiome can comprise of around 4,500 distinct bacterial types that help to digest food, synthesise vitamins and regulate the immune system. A balanced microbiome also influences metabolism, body weight and aspects of brain function. When this complex interdependence is knocked out of balance – a state called dysbiosis – the consequences can include digestive disorders, obesity, immune dysregulation and negative effects on mental health.

Despite this central role in health, the gut microbiome does not feature in standard chemical safety assessments. Toxicology tests have traditionally focused on direct effects on human cells or on target organisms such as crop pests. Regulators have generally assumed that chemicals designed to act on a specific biological target will leave non-target microbes unharmed.

The Cambridge team has challenged that assumption by providing systematic evidence that many such compounds actually harm gut bacteria. They have also used the large dataset from their screening research to build a machine-learning model that can predict if industrial chemicals – either already in use or still in development – are likely to damage gut microbes.

“We have found that many chemicals designed to act only on one type of target, say insects or fungi, also affect gut bacteria,” said Dr Indra Roux, a researcher at the Medical Research Council (MRC) Toxicology Unit at the University of Cambridge and first author of the study.

“We were surprised that some of these chemicals had such strong effects. For example, many industrial chemicals like flame retardants and plasticisers that we are regularly in contact with were not thought to affect living organisms at all, but they do,” she added.

Professor Kiran Patil, also in the University of Cambridge MRC’s Toxicology Unit and senior author of the study, emphasised the value of the dataset for future risk assessment.

“The real power of this large-scale study is that we now have the data to predict the effects of novel chemicals, with the aim of moving to a future where novel chemicals are safe by design,” he said. By incorporating gut microbiome toxicity into early-stage chemical design, industry could avoid products that erode microbial health before they reach the market.

The researchers argued that regulators should treat the gut microbiome as a key element of human physiology rather than an afterthought.

“Safety assessments of new chemicals for human use must ensure they are also safe for our gut bacteria, which could be exposed to the chemicals through our food and water,” said Dr Stephan Kamrad, who also contributed to the work of the MRC’s Toxicology Unit.

He added that routine toxicology protocols will need to evolve if they are to reflect the central role of the microbiome in health.

Very little information has existed about the direct effects of environmental chemicals on the gut microbiome and, in turn, on human health. The team believes that people are regularly exposed to many of the chemicals tested, yet the actual concentrations that reach the gut remain unknown. The toxic dose for bacteria may vary widely between compounds and between individuals, depending on diet, lifestyle and metabolism.

Patil underlined the need for studies that track real-world exposures rather than rely solely on laboratory tests.

“Now we have started to discover these interactions in a laboratory setting it is important to start to collect more real-world chemical exposure data, to see if there are similar effects in [human] bodies,” he said. Such work could involve detailed monitoring of chemical residues in food, water and blood, combined with high-resolution profiling of the microbiome and its metabolic products.

In the meantime, the researchers suggested several straightforward precautions that could limit unnecessary exposure to pollutants that harm gut bacteria. They advised people to wash fruit and vegetables thoroughly before consumption, to reduce pesticide residues and to avoid the use of pesticides in domestic gardens whenever possible.

For further reading please visit: 10.1038/s41564-025-02182-6

Digital Edition

Lab Asia Dec 2025

December 2025

Chromatography Articles- Cutting-edge sample preparation tools help laboratories to stay ahead of the curveMass Spectrometry & Spectroscopy Articles- Unlocking the complexity of metabolomics: Pushi...

View all digital editions

Events

Jan 21 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 28 2026 Tokyo, Japan

Jan 29 2026 New Delhi, India

Feb 07 2026 Boston, MA, USA

Asia Pharma Expo/Asia Lab Expo

Feb 12 2026 Dhaka, Bangladesh