William Smith: Seminal geology map rediscovered

- Published

A first edition copy of one of the most significant maps in the history of science has been rediscovered in time for an important anniversary.

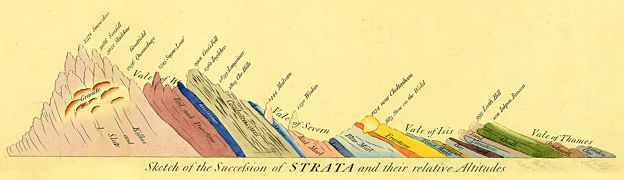

William Smith's 1815 depiction of the geology of England, Wales and part of Scotland is a seminal piece of work.

The first map of its kind produced anywhere in the world, only about 70 copies are thought to exist today.

Now, The Geological Society has turned up another in its own archives, ready to celebrate the map's bicentenary.

Tucked away in a leather sleeve case, the mislaid artefact was last seen roughly 40 or 50 years ago.

"It just wasn't where people expected it to be," said John Henry, the chairman of The Geological Society's History of Geology Group.

"I guess the person who put it away knew where it was, but then they left and that was it - it became lost," he told BBC News.

In one sense, the map is better for its abeyance because it means it has not been exposed to light, and that has protected its exquisite colours.

Smith spent the better part of 15 years collecting the information needed to compile the map.

It is said he covered about 10,000 miles a year on foot, on horse and in carriage, cataloguing the locations of all the formations that make up the geology of the three home nations.

An estimated 370 copies were produced. The outline of the geography and the strata were printed from copper plate engravings, but the detail was finished by hand with watercolours.

The lower edge of a formation is saturated and then the paint is made to fade back to the high edge.

It is this colouring technique, combined with the tendency of many of England's rocks to dip to the south or southeast, that gives Smith's map its iconic look.

The re-discovered copy comes in 15 separate sheets. These have no serial numbers on them, but that in itself is a clue to the map's position in the production sequence.

The first batch in the run is known not to have carried any numbering. Another clue is the geology of the Isle of Wight. Smith changed its depiction several times, and the re-discovered map displays his earliest efforts.

The artefact is certainly among the first 50 to come off the production line, and very probably among the first 10.

Quite what its value is - that is difficult to say. Possibly in the six figures.

The Geological Society has had the map fully restored and digitised. And from Monday, anyone will be able to view it online. The paper version will also go on display at the society's Burlington House HQ in London's Piccadilly.

William Smith (1769-1839) is often referred to as the "Father of English Geology" - a title bestowed on him by The Geological Society, which at first had been reluctant to embrace his vision.

The organisation's first members were drawn from the metropolitan elite, and they took a rather disdainful view of the blacksmith's son turned surveyor.

But the big landowners knew his worth. They brought Smith in to help them maximise the worth of their estates - to drain land, to improve the soil, to find building stone, and, above all, to find coal.

It is this work that would have brought him into contact with the rocks and with the fossils that would lead him to his greatest scientific contribution.

John Henry explained: "The concept which enabled him to do the mapping and that drove him along almost obsessively was this realisation that specific fossils were unique to a specific stratum, and that you knew where you were in a sequence if you could see what the fossils were. That was the breakthrough. People had been collecting them for a long time and naming them in the Linnaean way, but without any real idea that they were in a sequence. But Smith knew it."

Today, it is called the "principle of faunal succession", and this idea holds that because fossils succeed one another in order, rocks containing similar fossils are similar in age.

This principle has enabled scientists to construct the geological timescale by which the relative ages of rocks can be measured, and thereby understand the history of the Earth.

No wonder Simon Winchester called his 2001 book about William Smith, The Map that Changed the World.

Monday, 23 March, is Smith's birth date.

Sir David Attenborough is going to unveil a plaque at Smith's former residence at 15 Buckingham Street on London's Embankment.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos

- Published16 March 2015

- Published13 October 2014

- Published7 December 2009