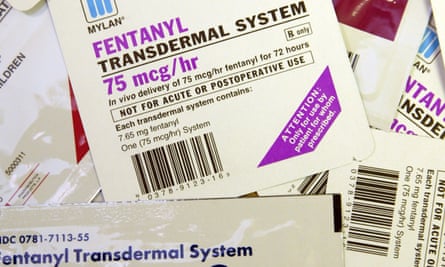

Fentanyl is the unbelievably potent opioid drug cited in the deaths of such stars as Michael Jackson, Tom Petty and Prince. Far from mansions and flash hotels, it is also the street-level heroin substitute that is at the centre of mind-boggling statistics for drug deaths across the US: about 64,000 people died from overdoses in 2016, up 21% on the previous year. Fentanyl is so toxic that even inhaling small particles can be dangerous, but for the amoral people selling it to the addicts who often use it intravenously, it has no end of advantages, starting with basic economics: whereas a kilo of heroin is said to cost $6,000 (£4,300) to produce and will sell for a few hundred thousand dollars, the respective figures for fentanyl are put at $4,000, and as much as $1.6m.

Inevitably, it is now coming to Britain. Last summer the National Crime Agency said that fentanyl had been cited in 60 deaths over the previous eight months, the majority of which had taken place in Yorkshire and the Humber. In Hull, where as many as 16 people are said to have died recently because of fentanyl overdoses, journalists found people who had been long-term heroin users who were sold batches cut with this new drug – which seemed to inspire a mixture of awe and fear. What they said was vivid, and frightening: “On a scale of one to 10, heroin is a two and fentanyl is an 11,”; “It just comatoses you and throws you to the floor”. Fentanyl and its derivatives have also been mentioned in reports from south London, Hertfordshire, Birmingham, Bristol and the Scottish borders.

The threat to lives from fentanyl is one relatively new element of a huge issue that has been intensifying for the past five years. Just over a year ago, the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs said that the number of reported drug deaths involving opioids including heroin had risen over the previous four years by 58% in England, 23% in Wales and 21% in Scotland.

The Office for National Statistics subsequently put deaths from the use of all drugs in 2016 at 3,744 in England and Wales, with fatalities from illegal substances reckoned to be 2,593, the highest figures since comparable statistics began. During the same period in Scotland, more than 850 people died after using drugs, more than double the figure of a decade before – and heroin and other opioids were implicated in 90% of those deaths.

Almost one in three fatal overdoses in Europe now happens in the UK. The highest rate of death is among people aged between 40 and 49, which leads some people to focus on the so-called “Trainspotting generation”, and the well-founded idea that long-term addiction has rendered many people ever more ill and fragile. The effects of recent austerity on advice and support services are another factor.

Add the new risk from synthetic opioids such as fentanyl, and you have the makings of a national tragedy that may yet escalate even further. It is all manifested in everyday life: syringes discarded in the park, burglaries carried out by desperate addicts, the down-page headline in the local paper about yet another death. Yet we continue to avert our eyes. And you wonder what number of annual drug deaths might finally change our minds.

And so to a ray of hope. When the first police and crime commissioners (PCCs) were elected on pathetically low turnouts back in 2012, plenty of people – including me – scoffed. But in a handful of areas in England and Wales, some PCCs are now trying to blaze a trail towards the kind of drugs policy that might move things out of their current dead end.

Among the most vocal is David Jamieson, the former Labour MP who is now PCC for the West Midlands. He speaks in the kind of gruff cadences that tend to convey “tough” positions, but he is convinced that most current approaches to so-called hard drugs are broken. “Nothing is getting better,” he told me last week. “People are doing good work in their own areas, but collectively, the whole thing is failing.”

One statistic, he said, illustrated how bad things have got: the fact that if you combined drug-related crime, use of the NHS, social care and drug-related deaths, heroin and crack users in the West Midlands cost the public purse £1.4bn a year. “It’s a truly awesome figure,” he said. And there are plenty of other facts that underline the futility of most existing drugs policy. “Whenever we break up a drug-dealing gang, within hours it’s backfilled by another one. And are we stopping the harm to the people who take the drugs? No.” Fentanyl, he said, was now “on our radar”.

Addicts, he insisted, needed to stop being funnelled towards courts and prisons and given treatment instead. More specifically, he wanted to take long-term heroin users away from the criminal demimonde via access to unadulterated supplies, prescribed by medical professionals who could also try to encourage them to get clean – an approach known as heroin-assisted treatment, which Jamieson suggested the Home Office was prepared to countenance so long as it wasn’t seen to take a lead. In addition, though he said there were accompanying issues that needed to be ironed out, he thought we ought to consider the kind of “fix rooms” common in Europe, where users could take drugs using clean syringes that could be safely disposed of, overseen by people who could both help them into treatment, and avert immediate disaster (witness one quote from a drugs worker in Copenhagen: “We have had hundreds of overdose situations, and not a single one has been fatal.”).

In Glasgow, the city’s Health and Social Care Partnership has serious plans to create just such a facility, which are backed by the Scottish government. But because drugs law is a matter for Westminster, the plan was overruled late last year. By way of explanation, the Home Office issued the same statement it seems to always drag out whenever the idea comes up: “A range of offences is likely to be committed in the operation of drug consumption rooms. It is for local police forces to enforce the law in such circumstances and, as with other offences of this type, we would expect them to do so.”

Whatever their intentions, the people responsible for this stubbornness end up encouraging crime and even death. The stakes are now far too high for such stupidity: to turn round the monologue from the Irvine Welsh novel that so brilliantly captured the heroin experience, they should choose life.